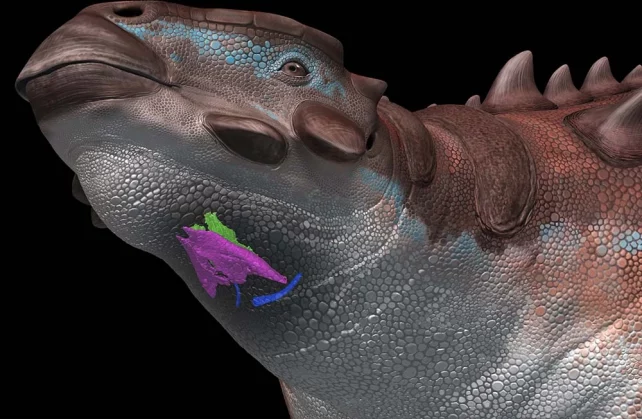

In a prehistoric forest, some 80 million years ago, a stocky, 5-meter-long armored dinosaur with a spiky back ambles about on four short legs, slowly chewing on a snack of plant material.

After it swallows, the flap of skin in its throat that blocks its voice box flips back open, allowing the dinosaur to take a deep breath in and let out a fearsome…

Chirp?

That's not exactly the most terrifying start to a scene in the next Jurassic World film, but it might be more realistic than a roar.

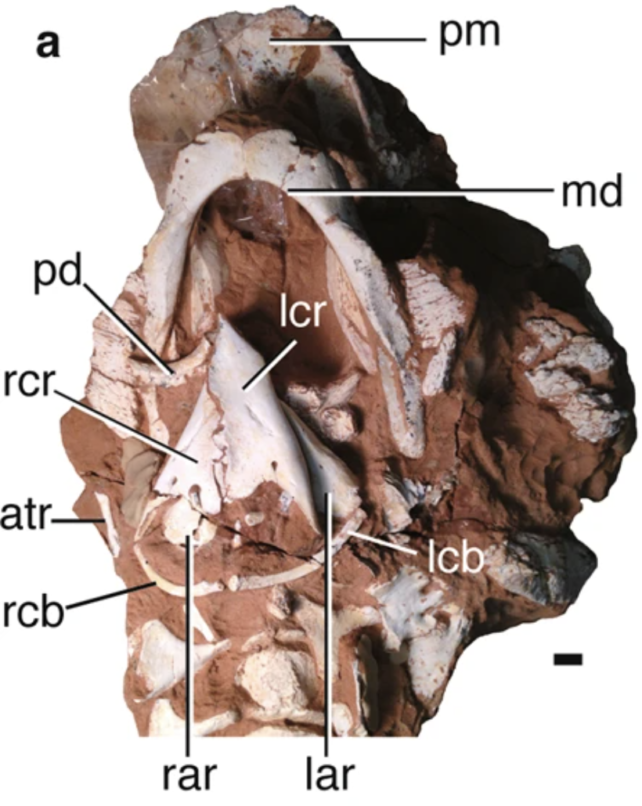

Soon after the fossilized body of a Cretaceous era ankylosaur named Pinacosaurus grangeri was discovered in the Gobi Desert Basin in Mongolia in 2005, its wonderfully preserved throat bones were hypothesized to play a role in breathing.

Now, paleontologists from Hokkaido University Museum in Japan and the American Museum of Natural History propose they actually form key parts of its voice box, the first ever to be discovered in a non-avian dinosaur.

In spite of the animal's relatively distant relationship to birds, the larynx holds several similarities with modern tweeters and chirpers. In fact, the vocalizing anatomy seems to be a strange hybrid between the voice boxes of reptiles and birds, the researchers say.

About 250 million years ago, reptile-like animals on Earth, called archosaurs, split into two groups: one featuring dinosaurs and pterosaurs, and another that contains crocodiles and alligators.

An ankylosaur like Pinacosaurus, researchers say, might have sounded like something in between those two lineages.

"Assuming that dinosaurs make some crocodile-like sounds is pretty safe," paleontologist Victoria Arbour, who was not involved in the study, told the New York Times.

"That's the base anatomy they'd be working with. And then birds evolved these additional ways of producing sounds where they can modify the sounds coming out of their throat in a more nuanced way."

The larynx is a hollow tube that sits at the top of the throat and contains anatomical features adapted to produce sound waves. When air is exhaled through the tube, folds of tissue vibrate at specific frequencies.

This is one way mammals, amphibians, and reptiles produce noise with their respiratory tract.

But birds are an odd exception. They have a 'syrinx' located at the opposite end of the windpipe to a larynx. For humans, it would be kind of like having a voice box in your chest.

The syrinx of a bird has two separate 'pipes', which allows them to make two different calls at once. Birds also have another structure sitting up higher in their windpipes that allows them to further modulate the sounds they are producing deeper down.

The whole network is quite complex, and yet scientists still don't really understand how it evolved from a larynx.

Modern birds are descended from avian dinosaurs, and yet because the voice box is made of soft tissue, very few ancient examples have been found in fossil form. The oldest avian syrinx ever found is 66 million years old and looks a lot like what geese and ducks have today.

Until now, however, a fossilized larynx has never been reported in a non-avian archosaur.

The Pinacosaurus fossil features a ring-shaped bit of cartilage in its larynx known as a cricoid, which is particularly large. Larger, the researchers say, than what is usually seen in the larynx of living reptiles.

Today, reptiles that are more vocal tend to possess larger cricoids, which means the size of this cartilage is a good indication of sound.

Compared to modern turtles, lizards, crocodiles, and birds, researchers say that Pinacosaurus has an elongated larynx. Unlike reptiles, this suggests the dinosaur wouldn't have used its larynx as a sound source but as a sound modifier.

Today, living birds modify sound using a different structure but in a similar way.

"Therefore," researchers write, "the larynx of Pinacosaurus may have been actively vocalized and associated with loud and explosive calls as in vocal reptiles and birds."

The authors aren't yet prepared to say what Pinacosaurus's voice actually sounded like, but they think its vocalizations were probably "related to courtship, parental call, predator defense, and territorial calls" and may have included cooing and chirping.

Yet even if this dinosaur had a larynx more similar to living reptiles, with no resemblance to a bird's syrinx, it's possible it could still make bird-like sounds.

The voices of turtles and other reptiles have been seriously overlooked by scientists in the past. Many of these creatures are simply assumed to be mute, when, in fact, they can make astonishingly diverse sounds, including coos, croaks, chirps, grunts, clicks, and even meows!

Clearly, researchers are still working out how the larynx and syrinx differ in their sound-producing abilities.

Without more evidence, who's to say prehistoric ankylosaurs couldn't have once sounded like cats?

Now that's an opening to the next Jurassic World that audiences wouldn't be expecting.

The study was published in Communications Biology.