Like the deserts of the Antarctic, or the deepest parts of the sea, Mono Lake in California is an inhospitable place for most life forms. Apart from bacteria and algae, it appears only brine shrimp and diving flies can put up with its super-salty waters.

But there's more to this body of water than meets the eye. Researchers at the California Institute of Technology have recently discovered eight more species of microscopic worm thriving in and around the lake, and one of them is a brand new kind of weird.

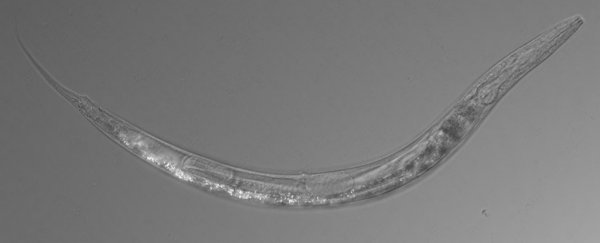

One of the newly-discovered species of nematode - for now called Auanema sp. - has not one, not two, but three different sexes, the team reports, and it can survive a dose of arsenic 500 times what is humanly possible.

When it comes to differentiation of the sexes, nematode species usually keep it simple, dividing into hermaphrodites and males. But Auanema sp. also has worms of the female sex. Furthermore, they have other interesting sex characteristics, as the researchers note "the arrangement of genital papillae in Auanema sp. males is unique in the genus."

As if that's not radical enough, the team says this microscopic worm also gives birth to live offspring, a unique approach in the typically egg-laying nematode world.

It's an extreme creature in an extreme place, and that's probably not a coincidence. The team thinks this worm's strange characteristics are part of what keeps it alive in the hyper-salty, alkaline waters of Mono Lake.

"Extremophiles can teach us so much about innovative strategies for dealing with stress," says Pei-Yin Shih.

"Our study shows we still have much to learn about how these 1,000-celled animals have mastered survival in extreme environments."

Comparing the strange new species of nematode to others in the same genus, the researchers found a similarly high arsenic resistance among two sister species.

And yet the curious thing was, none of these creatures actually lived in environments with high arsenic levels. There had to be another reason for this astonishing tolerance.

"Previous Auanema species were isolated from rich soils and dung, which can contain high concentrations of phosphate," the authors suggest.

"Since arsenic uptake occurs adventitiously via phosphate transporters, it is conceivable that adaptation to high levels of phosphate in the environment could lead to increased arsenic resistance as well."

In other words, nematodes might be pre-adapted to life as an extremophile. They could have a genetic resiliency and flexibility that makes it easier for them to live in harsh places like Mono Lake.

Before this study, only two other species had been found in this lake - which is three times as salty as the ocean and has an alkaline pH greater than baking soda. Yet even still, the discovery of eight more species wasn't all that surprising to researchers.

Nematodes are the most abundant type of animal on the planet, so even in the harsh environment of Mono Lake, there's a good chance you'll find them.

Over the course of two years, researchers from Caltech isolated nematodes from across the lake and found multiple niches in which these nematodes were thriving. And their numbers included microbe grazers, parasites and predators.

"Thus, nematodes are the dominant animals of Mono Lake in species richness," the authors conclude.

"Phylogenetic analysis suggests that the nematodes originated from multiple colonisation events, which is striking, given the young history of extreme conditions at Mono Lake."

To say these creatures are opportunistic is an understatement. For every human on Earth, there are roughly 57 billion nematodes, and in barely no time at all, these creatures can set up shop in some of the most extreme places on Earth.

"It's just so cool finding another place where there are lots of nematodes and not much else," geoscientist Tullis Onstott who was not involved in the study told The Scientist.

And who knows, maybe when there's not much else, there will still be nematodes.

The findings were published in Current Biology.