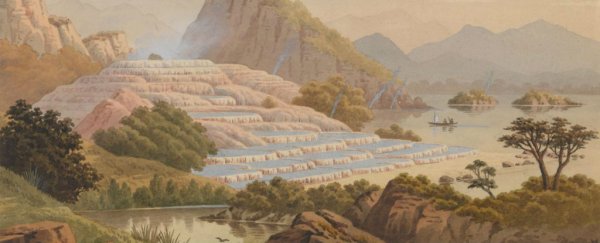

After more than a century of being buried by a volcanic eruption, New Zealand's long-lost pink and white terraces might have finally been rediscovered under layers of ash and mud.

Once hailed as a natural wonder of the world, and the largest silica deposits of their kind on Earth, it was feared that these terraces were destroyed by the 1886 eruption of Mount Tarawera. But now researchers say they've located where they were buried, and suspect some of them have been preserved this whole time.

"They became the greatest tourist attraction in the Southern Hemisphere and the British empire, and shiploads of tourists made the dangerous visit down from the UK, Europe, and America to see them," one of the team, Rex Bunn, told The Guardian.

"But they were never surveyed by the government of the time, so there was no record of their latitude or longitude."

During the heyday, the pink and white terraces of New Zealand were thought to be the largest silica 'sinter' deposits on the planet. Sintering occurs when a mineral spring or geyser deposits enough sediment to form a crust, creating natural mounds, terraces, or cones around the water supply.

There was a 'white terrace', which sat on the north-east end of Lake Rotomahana in northern New Zealand, and the 'pink terrace', which sat on another shore nearby.

It's thought that the pink hue found in some of the terraces was likely due to the presence of extensive colonies of a pigmented bacteria, such as Thermus ruber - relatives of the micro-organisms that inhabit the famously technicolour Morning Glory pool at Yellowstone.

Bunn, an independent researcher, got his big break in 2016 when Sascha Nolden from the National Library of New Zealand shared with him an old field diary he'd discovered some years prior.

The diary belonged to 19th century geologist Ferdinand von Hochstetter, who in 1859 was commissioned by the government of New Zealand to make a geological survey of the islands.

In his notes, von Hochstetter had recorded raw data from a compass survey of Lake Rotomahana, located 20 kilometres (12 miles) to the south-east of the city of Rotorua in northern New Zealand.

Because this was almost three decades before the volcanic eruption, the pink and white terraces were plainly marked in the area.

So, case closed? Not quite, because that eruption didn't just bury one of the world's most spectacular natural wonders - it shifted the landscape around it so severely that even an 'X marks the spot' no longer applies today.

Bunn and Nolden set about reconstructing von Hochstetter's lake map using a technique called forensic cartography, which involved comparing current topographic maps to the 1859 data, and matching up certain geological features until they'd narrowed down the most likely location of the terraces.

That might sound fairly simple, but the actual process was far from it.

"We would have put in 2,500 hours of research in the last 12 months," Bunn told Hannah Martin at Stuff.co.uk.

"We're confident, to the best of our ability, we have identified the terrace locations. We're closer than anyone has ever been in the last 130 years."

That last point is important - there have been several claims in recent years from other teams that they'd found the terraces, with some dispute over whether the landmark had been destroyed or partially preserved in the eruption.

Based on their research, Bunn claims to have developed an algorithm that's pinpointed the location of the pink and white terraces with a margin of error of plus or minus 35 metres.

He says when you're talking about a landmark that spans hundreds of metres, that's a close enough estimate to make digging them out a reality.

The decision to excavate the area has been given to the local Tuhourangi tribal authority, but Bunn expects that if they do decide to dig the terraces out, they will find some part of them still intact.

It's too soon to know if Bunn's and Nolden's claims of locating the terraces, and their continued existence, will pan out, but it would be incredible if they did.

As Bunn told Martin, "The pink and white terraces may in some small way return, to delight visitors to Rotorua as they did in the 19th century."

The research has been published in the Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand.