A particularly aggressive form of childhood cancer that forms in muscle tissue might have a new treatment option on the horizon.

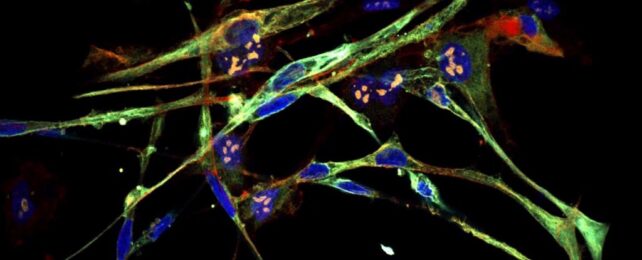

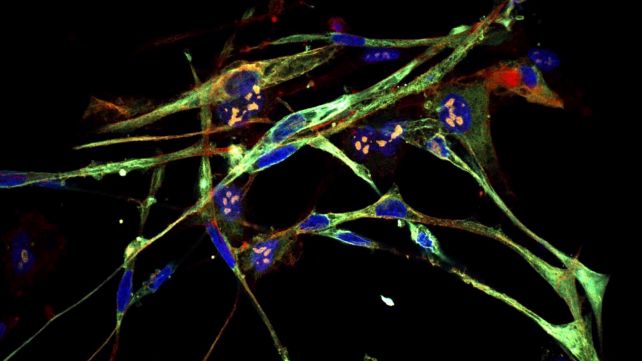

Scientists have successfully induced rhabdomyosarcoma cells to transform into normal, healthy muscle cells. It's a breakthrough that could see the development of new therapies for the cruel disease, and it could lead to similar breakthroughs for other types of human cancers.

"The cells literally turn into muscle," says molecular biologist Christopher Vakoc of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

"The tumor loses all cancer attributes. They're switching from a cell that just wants to make more of itself to cells devoted to contraction. Because all its energy and resources are now devoted to contraction, it can't go back to this multiplying state."

Cancer isn't a monolithic thing. It arises when cells from different parts of the body mutate. Rhabdomyosarcoma is a type of cancer that's most often seen in children and adolescents. It usually starts in the skeletal muscle when cells therein mutate and start multiplying and taking over the body.

Rhabdomyosarcoma is aggressive, and often deadly; survival rates for the intermediate risk group are between 50 and 70 percent.

One treatment option that's shown promise is called differentiation therapy. It emerged when scientists noticed that leukemia cells are not fully mature, similar to undifferentiated stem cells that haven't yet fully developed into a specific cell type. Differentiation therapy forces those cells to continue their development and differentiate into specific mature cell types.

In previous work, Vakoc and his team effectively reversed the mutation of the cancer cells that emerge in Ewing sarcoma, another childhood cancer that usually emerges in the bones.

The researchers wanted to see if they could repeat their success with rhabdomyosarcoma, for which differentiation therapy was thought to be decades away.

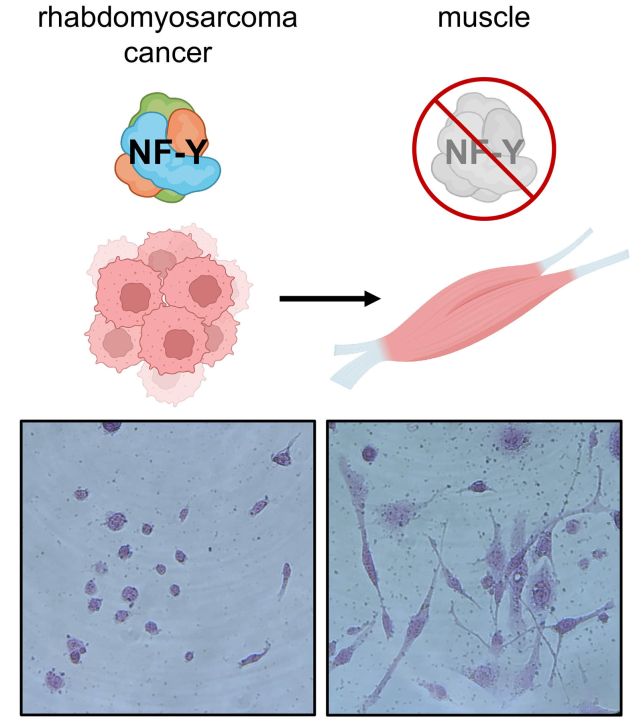

They used a genetic screening technique to narrow down the genes that might force rhabdomyosarcoma genes to continue their development into muscle cells. They found the answer in a protein called Nuclear transcription factor Y (NF-Y).

Rhabdomyosarcoma cells produce a protein called PAX3–FOXO1 that drives the proliferation of the cancer, and on which the cancer is dependent.

The researchers found that knocking out NF-Y inactivates PAX3-FOXO1, which in turn forces the cells to continue their development, differentiating into mature muscle cells with no sign of cancer activity.

This, the team say, is a key step in the development of differentiation therapy for rhabdomyosarcoma, and could accelerate the timeline for which such treatments are expected.

And they say that their technique, now demonstrated on two different types of sarcoma, could be applicable to other sarcomas and cancer types, since it gives scientists the tools needed to find how to cause cancer cells to differentiate.

"Every successful medicine has its origin story," Vakoc says. "And research like this is the soil from which new drugs are born."

The research has been published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.