It could soon be possible to measure changes in depression levels like we can measure blood pressure or heart rate.

In a new study, 10 patients with depression that had resisted treatment were enrolled in a six-month course of deep brain stimulation (DBS) therapy. Previous results from DBS have been mixed, but help from artificial intelligence could soon change that.

Success with DBS relies on stimulating the right tissue, which means getting accurate feedback. Currently, this is based on patients reporting their mood, which can be affected by stressful life events as much as it can be the result of neurological wiring.

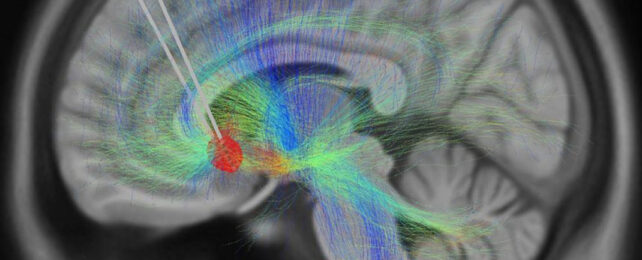

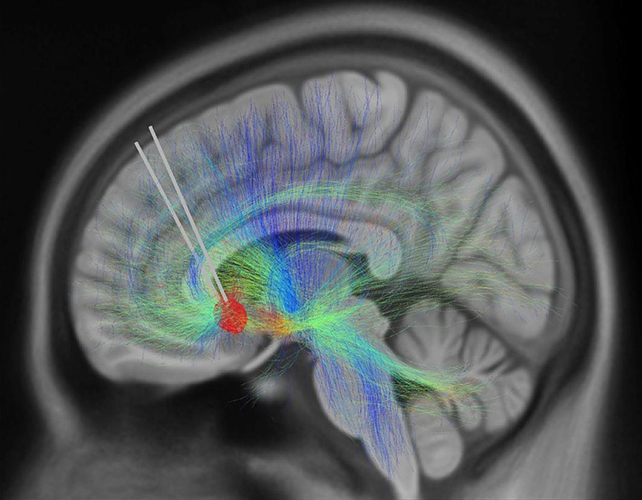

With that in mind, scientists in the US used a combination of electrode implants and AI analysis to try to pinpoint changes in brain activity patterns triggered by DBS.

The team from the Georgia Institute of Technology, the Emory University School of Medicine, and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai was able to identify a brain signal to use as a biomarker linked to recovery from depression.

The recovery signal provides a hugely useful indicator of when DBS is working and when it isn't. It seems to be more than 90 percent accurate in its feedback.

"Nine out of 10 patients in the study got better, providing a perfect opportunity to use a novel technology to track the trajectory of their recovery," says neurologist Helen Mayberg from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

"Our goal is to identify an objective, neurological signal to help clinicians decide when, or when not, to make a DBS adjustment."

The AI was trained using images of the participants' brains at the start and end of the process, giving it the opportunity to spot neurological differences that the human eye might miss. One of the patients responded well to treatment for four months before relapsing, for example – and the recovery signal disappeared a month before the relapse.

Now the AI has been trained, it can be used in further studies like this, giving researchers a much better set of data than they get with self-reporting alone. The next time there's a sign of a relapse, the DBS treatment can be adjusted to try and prevent it.

There's still lots of work to do, and not everyone wants electrodes implanted in their brain (it comes as part of DBS, which is why scientists could use it here). However, this shows potential for a major shift in the way depression is monitored and in how treatments are tailored for individual people.

"We showed that by using a scalable procedure with single electrodes in the same brain region and informed clinical management, we can get people better," says neuroscientist Christopher Rozell from the Georgia Institute of Technology.

"This study also gives us an amazing scientific platform to understand the variation between patients, which is key to treating complex psychiatric disorders like treatment-resistant depression."

The research has been published in Nature.