Alzheimer's is an insidious disease. Long before even the earliest symptoms begin to show, plaques of amyloid beta proteins and tangles of tau proteins are already building up in the brain.

Excessive daytime napping is one of the earliest outward signs, but exactly why that might be is hard to say. Some have suggested that Alzheimer's disease (AD) disrupts sleep-promoting brain regions, while others say a lack of sleep is what drives cognitive decline.

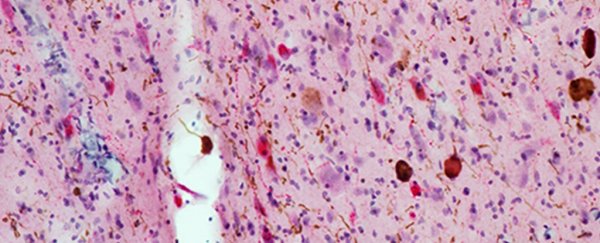

Researchers at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) have now put forward a new explanation. Analysing postmortem brain tissues from 13 patients with AD and 7 healthy controls, the team suggests that Alzheimer's disease directly attacks brain regions that keep us awake during the day.

"It's remarkable because it's not just a single brain nucleus that's degenerating, but the whole wakefulness-promoting network," says lead author Jun Oh, who researches memory and ageing at UCSF.

"Crucially this means that the brain has no way to compensate because all of these functionally related cell types are being destroyed at the same time."

Disrupted sleep has been associated with β-amyloid plaques before, but so far, little is known about the role of the other main AD marker, the tau protein tangles. Mounting evidence in the past few years has suggested this is an important avenue to explore.

While both tau and β-amyloid are hallmarks of Alzheimer's disease, an overabundance of the former might contribute more to brain degeneration, directly driving symptoms like fragmented sleep.

A study published earlier this year, for example, found that older people who display less slow-wave sleep have higher levels of the brain protein tau. At the time, the authors suggested that while these patients were sleeping for longer, the disrupted nature of this sleep was causing excessive daytime napping.

Oh and his colleagues have a different theory. Rather than stemming from a lack of sleep from the night before, they suggest that excessive daytime sleepiness is caused by direct degeneration of wake-promoting neurons.

Looking at brain tissue, the team found a significant tau buildup in three wakefulness-promoting brain centres, including the locus coeruleus (LC), the lateral hypothalamic area (LHA), and the tuberomammillary nucleus (TMN). Remarkably, this complex system had lost as many as 75 percent of its neurons.

"Our work shows definitive evidence that the brain areas promoting wakefulness degenerate due to accumulation of tau – not amyloid protein – from the very earliest stages of the disease," says senior author Lea Grinberg, a neurologist and pathologist at UCSF.

Among the many fatalities was a type of neuron in the LHA that produces a neuropeptide called orexin. This neuron plays a crucial role in wakefulness; when it is deleted in mouse models, the animals show similar patterns to human narcolepsy - a chronic sleep disorder characterised by daytime drowsiness.

In the brains of patients with AD, UCSF researchers found orexin practically annihilated. In fact, the abundance of these orexin-producing neurons had decreased by more than 71 percent.

"To put this into another perspective, patients with narcolepsy .. have been reported to show 85-95 [percent] reduction in the number of orexinergic neurons, almost comparable to what we see in patients with AD," the authors write.

While Alzheimer's is most often associated with memory problems, sleep problems are a common complaint that can show up much sooner. As such, scientists are now curious if excessive napping can somehow help us diagnose Alzheimer's earlier and more effectively.

"The study supports the idea that sleep dysfunction is a manifestation of Alzheimer's pathology buildup in the brain, rather than a risk factor," Ginberg told Newsweek.

"It opens opportunities to treat the cause rather than the symptoms."

The findings have been published in Alzheimer's & Dementia.