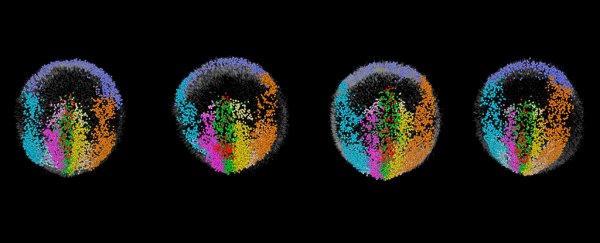

Using a newly developed microscopic technique, scientists have been able to create a detailed, 4D image of early mouse embryo development, down to the single cells involved – a fascinating look into the very first stages of life for mammals.

The imaging process is technically known as adaptive light-sheet microscopy, and it pushes the boundaries of what's possible in imaging.

This unprecedented look at organs and tissues being knitted together is going to help future research into organ regeneration, and health issues that can develop in the womb – any kind of work involving organ development or repair can benefit from this in-depth "cellular-resolution building plan" of mouse growth.

"To do any of that, you first need to understand how organs form," says one of the team, developmental biologist Kate McDole from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute in Maryland. "You need to actually see what happens in a real embryo."

The microscope works by using super-thin laser beams to illuminate cells as they go about their business. Cameras are then used to record the lit cells and track their movements in real time, leading to some of the dramatic videos – like the one above.

We're talking about the very first days of a mouse embryo's life, which we'd previously not been able to study in this detail. Organs are just beginning to form and the scientists have been able to capture the initial beats of the mouse heart too.

It's what's known as gastrulation in mammals, and it's something scientists are striving to understand more about.

The smart software attached to the microscope is continually making new decisions about how best to light up and focus on the embryo as it grows. It's because of these algorithms that such a complex embryo can be plotted like this – previous research had focused on the simpler embryos of zebrafish and fruit flies.

Rendering of the new microscope. (Howard Huighes Medical Institute)

Rendering of the new microscope. (Howard Huighes Medical Institute)

In fact the new system is so good that the scientists can plot the journeys of individual cells: where they go, the genes they turn on, and the other cells they meet on their travels.

Further computer programs were used to plot an "average" mouse embryo from four different experiments, and to log when and where cells were dividing.

This is now the sixth such microscope that the same team has built, and each one is getting more precise, more capable, and more useful.

For now the microscope can only track mouse embryos held in very particular lab conditions over the course of two days, but there's plenty of potential here for the tools and techniques to improve in the future (and they've already come a long way).

This could put science on the way to unlocking the mysteries of gastrulation – exactly how mammals develop from a single cell to an embryo. With that in mind, the team has put all its work online for other scientists to use.

"If you took all the building materials for a house and threw them in a pile, you don't magically get a house," McDole told Cassie Martin at Science News. "Contractors use plans to build the house."

"Being able to see how embryos actually make organs is a huge step forward."

The research has been published in Cell.