Chronic blood shortages are driving a search for a universal blood system that would allow doctors to save more lives. Researchers may have just brought us a step closer, by creating miniscule silicon coats for donated blood cells to wear.

Incredibly, the new nanotechnology allowed biomedical engineer Chuanyi Lei from South China University of Technology and colleagues to successfully transfuse blood between species.

"Silicified red blood cells not only escape immune activation in different species, but also function perfectly for oxygen transport," the team writes in their paper.

A number of factors have conspired to create a blood shortage in the US, including policy changes to protect donors and the COVID-19 pandemic. Donation is at its lowest in 20 years.

"A person needs lifesaving blood every two seconds in our country – and its availability can be the difference between life and death," chief medical officer of the American Red Cross, Pampee Young, said during an emergency shortage in January this year.

"One of the most distressing situations for a doctor is to have a hospital full of patients and an empty refrigerator without any blood products."

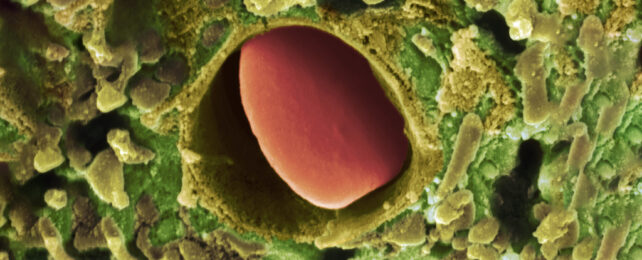

By building a silicon coating for blood cells, Lei and team were able to cover the surface proteins that our bodies use to recognize blood types. This allows a different blood type to be safely used, including blood from another species.

The team successfully transfused these silicon clothed human blood cells into mice.

The best part: in every test so far, the cloaked cells otherwise act just like naked red blood cells. Their membrane remains intact, they can still float through blood plasma, produce their usual cellular fuel, and carry vital oxygen to where it's needed.

"The silicified blood retains all essential functions of red blood cells, has superior mechanical properties, is resistant to adverse environmental conditions, can be stored for extended periods, and is highly effective in preventing immune system activation," the team explains.

The authors have identified an opportunity to reduce blood usage by providing an alternative fluid to store donor organs in.

Artificially pumping blood through these organs keeps them alive for long enough to be transplanted, but it uses a lot of blood. With the silicon coat strategy, it might be possible to tap into animal sources instead of using limited human blood supplies.

Lei and colleagues successfully performed a liver organ transplant in a rat using their fortified blood system.

"These results highlight the immense potential of silicified erythrocytes [red blood cells] as a safe and efficient transfusion alternative, which effectively meets the growing clinical demand for blood," the researchers conclude.

Of course, this new blood technology is still in its infancy so it has many more challenges to endure before it can be determined safe for humans.

Meanwhile, for those of us in good health, donating blood remains a valuable way to help address current shortages and potentially save lives.

This research was published in PNAS.