Americans are taking more prescription drugs and staying on them for longer than ever before, according to new research.

The first study to estimate the lifelong burden of prescription drugs in the United States predicts that babies born in 2019 will spend half their lives taking meds of some sort under doctor's orders.

The study was conducted by sociologist Jessica Ho from Pennsylvania State University and is based on data from 1996 to 2019, which was taken from a long-running, annual national survey on annual drug use in the US.

"This paper is not trying to say that use of prescription drugs is good or bad," Ho says. "Obviously, they have made a difference in treating many conditions, but there are growing concerns about how much is too much."

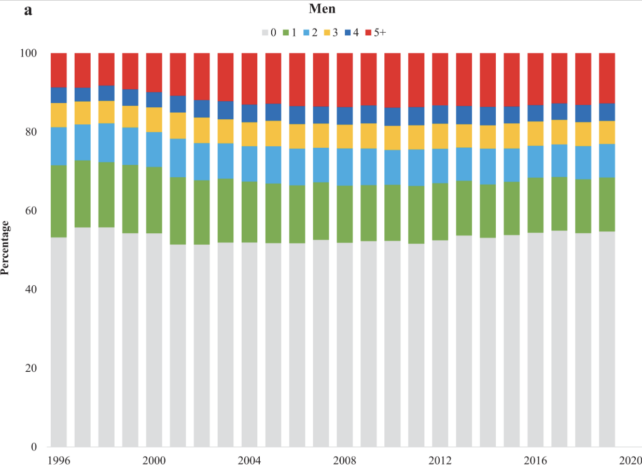

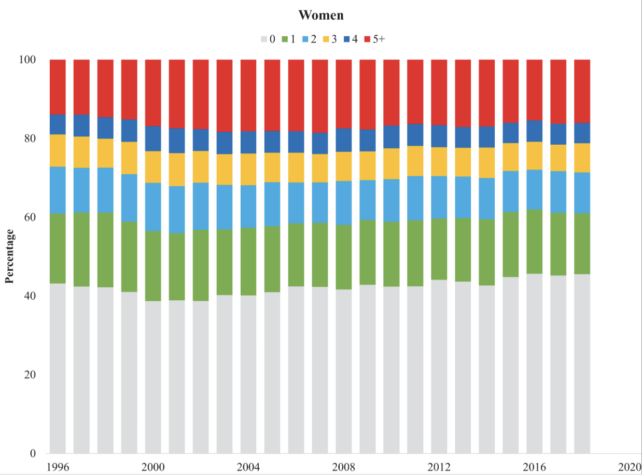

The findings reveal a steep increase in prescription drug use among both sexes, nearly every age group, and all considered races, but especially among older, White women.

"The share of Americans' lives spent simultaneously taking large numbers of drugs is substantial and expanded dramatically over time," writes Ho.

"These trends are likely related to several factors, including the growing burden of obesity, longer survival with chronic conditions, and the intensification of treatment of high blood pressure and cholesterol."

But it's also true that life expectancy in the US has generally increased over time. Ho suggests the influence of the pharmaceutical industry and the current culture and constraints of the medical system have also played important roles in the rise of prescription drugs.

In 1996, Ho's study revealed no men of any age could expect to take five or more drugs for more than a third of their remaining life.

By 2019, men and women above the age of 50 could expect to take five or more drugs for around half their remaining lives.

For older men born in later years, prescription drugs for hypertension increased "tremendously", nearly doubling over the study period. For women, the largest increases in drug prescriptions were for antidepressants.

"A newborn girl in 1996 could expect to take antidepressants for 5.55 years; by 2019, this figure more than doubled to 12.52 years," Ho writes.

At every age, women were found to take more drugs and for longer than their male counterparts.

The average, male baby born in 2019, for instance, could expect to take prescription drugs for 37 years of his life in Ho's study.

By comparison, a female baby born in 2019 was expected to take prescription drugs for 48 years of her life.

Part of the difference is that women live longer than men and are prescribed medications much earlier on in life. Only by age 40, for instance, are half of all men taking prescription drugs. Women hit that mark at age 15.

"Gender differences in drug use are multifaceted and related to many factors, including the fact that contraceptives remain largely targeted toward women," Ho writes.

Compared to White people, Ho found Black people and Hispanic people spend longer periods of their lives taking no prescription medicines at all.

Because these groups also experience higher mortality than White people, the difference is likely due to inequality in medical care.

But while it's true that many prescription medicines can help manage disease and improve health and life expectancy, more drugs isn't necessarily better. A "pill for every ill" can come with some serious unintended downsides.

The more drugs a person takes, the higher the risk of side effects and negative interactions, leading to an increased risk of falls, cognitive issues, and death.

Each year in the US, about 1.3 million emergency department visits are due to adverse drug effects, mostly from blood thinners, diabetes medications, heart medications, seizure medications, and opioid painkillers.

In fact, prescription medications are a leading cause of death in health systems around the world, not just the US.

The United Nations has warned that each year, medication errors to do with prescribing, dispensing, administration, and monitoring cost the world US$42 billion.

Older people are particularly vulnerable to negative drug outcomes as they not only take more medication in general, but they are also more likely to forget when or how to take the drugs.

'Deprescribing' unnecessary medications in a monitored setting could improve the quality of life and lighten the financial burden for millions of patients, although scientists are still researching how to do so safely and effectively.

"Americans are taking statins, antihypertensives, and antidepressants for large and growing portions of their lives," Ho writes.

"However, for a phenomenon that occurs across so much of the life course and has enormous potential to affect health, well-being, and other outcomes, it remains surprisingly understudied."

From now on, Ho argues it's essential that we study how high, sustained levels of prescription drugs, taken for years to decades, actually impact health and well-being in the long run.

The study was published in Demography.