A fast-flowing river of molten iron has been found surging under Alaska and Siberia, some 3,000 km (1,864 miles) below the surface - and it appears to be speeding up.

This colossal jet stream, which is estimated to be about 420 km wide (260 miles) and nearly as hot as the surface of the Sun, has tripled in speed in less than two decades, and is now headed towards Europe.

"We know more about the Sun than Earth's core," says one of the team, Chris Finlay from the Technical University of Denmark. "The discovery of this jet is an exciting step in learning more about our planet's inner workings."

Finlay and his team detected the jet stream while analysing data from the European Space Agency's (ESA) trio of satellites, called Swarm.

Launched in 2013 to measure fluctuations in Earth's magnetic field, these satellites allowed the researchers to create a kind of x-ray of the planet's inner structure, revealing vast components that we didn't even know existed before.

"The European Space Agency's Swarm satellites are providing our sharpest X-ray image yet of the core," says lead researcher Phil Livermore from the University of Leeds in England.

"We've not only seen this jet stream clearly for the first time, but we understand why it's there."

Earth's magnetic field is thought to be generated by the activity going on deep inside the planet's core.

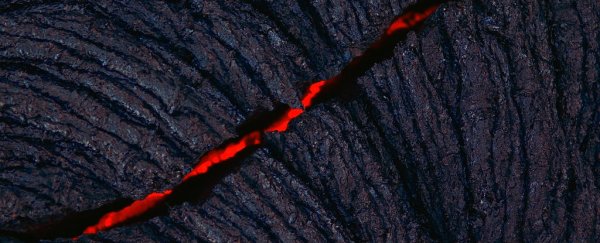

The core itself is a solid lump, two-thirds the size of the Moon, and composed mainly of iron. With a temperature of around 5,400 degrees Celsius (9,800 degrees Fahrenheit), it's almost as hot as the surface of the Sun, which hits an intense 5,505 °C (9,941 °F).

Surrounding the solid inner core is Earth's outer core - a 2,000-km-thick (1,242-mile) layer made primarily of liquid iron and nickel.

Differences in temperature, pressure, and composition in this layer create movements and whirlpools in the liquid metal, and together with Earth's spin, they generate electric currents, which in turn produce magnetic fields.

When the researchers examined satellite data from the outer core area in the northern hemisphere, they found strange 'lobes' of magnetic flux beneath Alaska and Siberia.

But the lobes weren't stuck in those positions - they're moving in the direction of the European continent, and the team says they're being pushed along by a jet stream of molten iron.

"Because their motion could originate only from the physical movement of molten iron, the lobes served as markers, allowing the researchers to track the flow of iron," Andy Coghlan reports for New Scientist.

The team found that this jet stream has accelerated in speed since 2000, and is now pushing the lobes under Alaska and Siberia at a rate three times faster than typical outer core speeds, and hundreds of thousands of times faster than the speed of Earth's tectonic plates.

"This jet of liquid iron is moving at about 50 kilometres per year," Finlay told at BBC News.

"That might not sound like a lot to you on Earth's surface, but you have to remember this a very dense liquid metal and it takes a huge amount of energy to move this thing around, and that's probably the fastest motion we have anywhere within the solid Earth."

At this stage, it's not clear why the jet stream is accelerating, but the researchers suspect it's a natural part of Earth's inner cycle that's been going on for billions of years.

If we can figure out where in the cycle we're at right now, we could predict how Earth's magnetic field will change over time - including how it might reverse in the coming centuries.

As New Scientist explains, since Earth's magnetic field seems to have been weakening at a rate of about 5 percent per century, the magnetic field is expected to flip, at which point the magnetic north and south poles will trade places.

"Further surprises are likely," ESA's Swarm mission manager, Rune Floberghagen, said in a press statement.

"The magnetic field is forever changing, and this could even make the jet stream switch direction."

The study has been published in Nature Geoscience.