Twenty years ago, Kathleen Folbigg was imprisoned, having been found guilty of killing her four children. A few days ago, she received a full pardon and walked free.

A mutation in a CALM gene that affects one in 35 million people is now thought to have caused the deaths of her two daughters via a rare syndrome called calmodulinopathy.

Only 135 people worldwide have been known to have this mutation, so Folbigg's family is likely to be the only case in Australia. A different mutation could be responsible for the deaths of her two sons.

In 2003, a jury concluded that Folbigg had smothered each of her children to death over a decade; Caleb at 19 days of age, Patrick at 8 months, Sarah at 10 months, and Laura at 18 months.

Folbigg was found guilty of three counts of murder and one count of manslaughter. She became known as Australia's "worst female serial killer".

Folbigg has always maintained her innocence. There was no evidence of smothering or injuries to the children. The trial focused on circumstantial evidence, namely Folbigg's diary, in which she wrote that "guilt about them all haunts me" and detailed her struggles with motherhood.

Back then, the human genome had just been sequenced for the first time at a cost of US$300 million, so it was not possible to examine the children's DNA for mutations that could explain their sudden deaths.

By 2015, however, the price of sequencing the human genome had dropped to US$1,500. And some research had been done on CALM gene mutations that could help explain what happened to the Folbigg children.

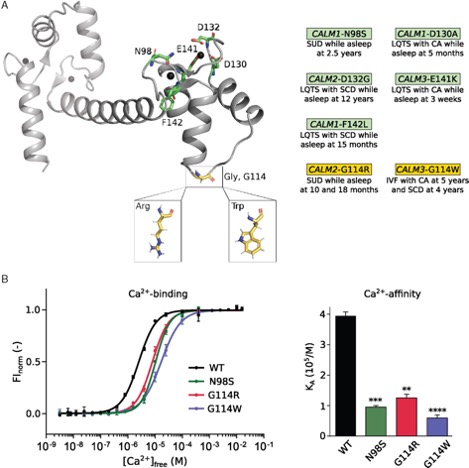

Three CALM genes – CALM1, CALM2, and CALM3 – encode the exact same protein, calmodulin, which is essential for life.

Humans need all three CALM genes working so that the body can manufacture enough of this protein to control the movement of calcium around cells.

The protein calmodulin helps control the rhythmic contraction of the heart by opening and closing calcium channels in heart muscle cells.

In 2012, scientists found that a mutation in a single amino acid in the CALM1 gene caused irregular heartbeats and cardiac deaths in a large Swedish family.

A study in 2013 found that two infants had experienced multiple cardiac arrests due to a mutation in the CALM1 or CALM2 genes. Another type of mutation in CALM2 caused cardiac arrest in two children in a 2016 study.

In a group of 74 children with a mutation in a CALM gene, 27 percent died from a heart condition at an average age of 6, a 2019 study found.

By this time, Folbigg's appeal had been rejected, but her sentence had been reduced slightly.

During an inquiry into her case in 2019, genetics experts presented data on CALM mutations and linked them to sudden infant deaths.

But, while CALM mutations were found in two of the female children's genomes, there was a lack of data showing that these particular mutations were deadly, and Folbigg was returned to prison.

A study published in 2020 found that Laura and Sarah had two novel CALM2 mutations that structurally altered their calmodulin proteins. In lab experiments, the researchers showed that these mutated proteins could not bind to or regulate two pivotal calcium ion channels.

The two Folbigg girls had respiratory issues prior to their deaths, which can precede sudden cardiac death in children.

The two boys, Caleb and Patrick, did not have CALM mutations, the study found. However, they had one copy of a mutated BSN gene.

Around half of mice with this mutation die before six months and all have recurrent seizures. This mutation may explain Patrick's blindness and epileptic seizures and could account for his early death.

All this evidence culminated in a petition for Folbigg to be pardoned. This petition was signed by 90 scientists and sent to the governor of New South Wales in 2021.

The petition said that Folbigg's conviction was "based on the proposition that the likelihood of four children from one family dying of natural causes is so unlikely as to be virtually impossible. This is flawed logic."

A second inquiry was launched last year, and Folbigg was finally pardoned on 5 June 2023. Folbigg will not serve out the next 10 years of her 30-year sentence.

If her conviction is overturned in the Court of Criminal Appeal, which could take up to a year, she could sue the government for millions in compensation.

"Today is a victory for science and especially truth," Folbigg said upon being released from prison.

"And for the last 20 years I have been in prison I have forever and will always think of my children, grieve for my children, and miss them and love them terribly."