A massive 19th century storm in the pacific United States opened up a 300-mile-long (480-km-long) sea that stretched through much of the central part of California. And it looks like the state is due for another megaflood.

For 43 days, from late 1861 to early 1862, it rained almost nonstop in central California. Rivers running down the Sierra Nevada mountains turned into torrents that swept entire towns away. The storm was caused by an atmospheric river, a large concentration of water vapour that can cause devastating storms.

"[These storms] have the potential of hurricanes - or even more so because they go on for weeks," Lucy Jones of the US Geological Survey told NPR.

Atmospheric rivers carry concentrated channels of water vapour out of the tropics. A famous example is the Pineapple Express, which, propelled by the jet stream, carries vapour from the waters near Hawaii all the way to the American Pacific coast, where it causes heavy storms.

A strong atmospheric river is capable of carrying more than 10 times the average amount of water that passes through the mouth of Mississippi River.

That translates to a crazy amount of rain. And, at least one year, it was enough to flood large swathes of the state.

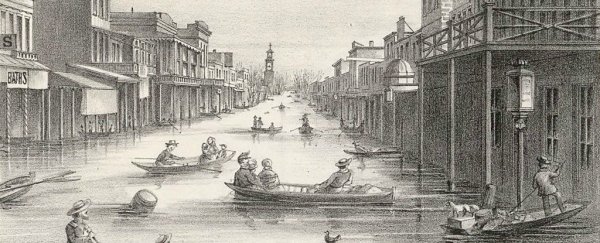

On 10 January 1862, the day California's new governor elect, Leland Stanford, was to be inaugurated, a massive flood broke through the levees surrounding Sacramento, covering the city in 10 feet (3 metres) of brown, debris-filled water.

As Scientific American reported, the government rushed through the inauguration, even though Stanford had to travel by rowboat from the governor's mansion to the statehouse. When he returned to his home, he had to row to a second-storey window to enter. On January 22, the California legislature had to be moved to San Francisco, where it stayed for six months as Sacramento dried out.

The flooding was so intense that California's 300-mile-long (480-km-long) and 20-mile-wide (32-km-wide) Central Valley turned into a massive inland sea.

The botanist William Henry Brewer was travelling through the region during the flooding, and described the destruction in letters to his brother on the East Coast, published in the book Up and Down California in 1860-1864, including this one dated 31 January 1862:

"Thousands of farms are entirely under water - cattle starving and drowning. All the roads in the middle of the state are impassable; so all mails are cut off. The telegraph also does not work clear through.

In the Sacramento Valley for some distance the tops of the poles are under water. The entire valley was a lake extending from the mountains on one side to the coast range hills on the other. Steamers ran back over the ranches fourteen miles from the river, carrying stock, etc, to the hills.

Nearly every house and farm over this immense region is gone. America has never before seen such desolation by flood as this has been, and seldom has the Old World seen the like."

One in eight houses were destroyed or carried away in the flood waters. It was also estimated that as much as a quarter of California's taxable property was destroyed, which bankrupted the state. The flood decimated California's burgeoning economy. An estimated 200,000 cattle drowned, about a quarter of all the cattle in the ranching state (the disaster shifted the California economy to farming).

Worse, this megastorm could happen again.

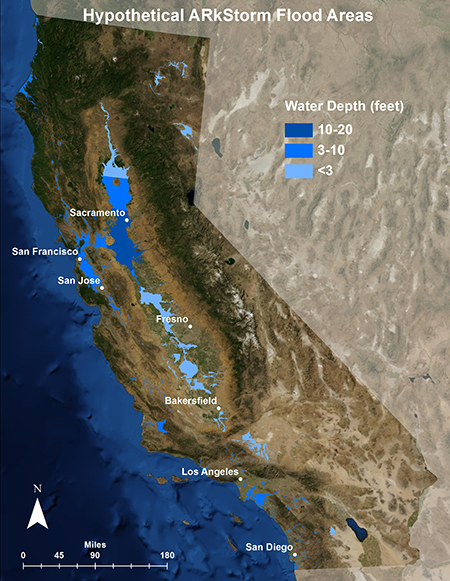

Geological studies have shown that major flooding occurs in California every 100 to 200 years, and the US Geological Survey has developed a projection called ARkStorm to assess how the state could handle another massive flooding disaster.

The projection below is a combination of two recent large storms in 1969 and 1986. The ARkStorm scenario represents what would happen if both storms happened back to back.

USGS

USGS

"We have geological evidence through flood deposits that even bigger storms than 1861 happened about once every 300 years. We have six events in 1,800 years of geological record," Jones said on the USGS's CoreCast podcast. "So we think this event happens, you know, once every hundred, 200 years or so, which puts it in the category as our big San Andreas earthquakes."

This article was originally published by Business Insider.

More from Business Insider: