Radiation therapy helps treat many cancer patients, particularly those with brain and lung tumours. But although it's effective, it can also cause memory loss, learning impairment and mental fogginess as a side effect.

Now in a promising new study, researchers have shown that an injection of human stem cell-derived brain cells can trigger the nerve cells in rats to repair themselves, allowing them to transmit messages again.

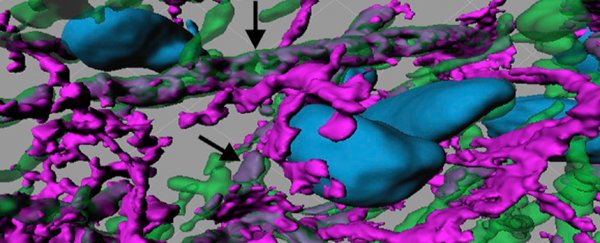

The researchers from the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Centre in the US took human embryonic stem cells and used signalling factors to coax them into differentiating into a type of brain cell that's often killed by radiation-related treatments, called oligodendrocytes, which produce the substance that coats nerve cells (action shown in green in the image above).

When oligodendrocytes die off, it can lead to mental impairment, which is a problem particularly for survivors of childhood cancer, who can fall behind in school work as a result of their treatment and suffer from reduced IQ into adulthood.

"Some cancer patients who receive radiation to the brain eventually experience cognitive problems, such as learning or thought-processing difficulties, or reduced motor skills," said the neurosurgeon who led the research, Vivian Tabar, in a press release.

"Sometimes brain radiation can't be used, especially in children, because the side effects are so damaging. But with a way to fix the problem, the risks could become more manageable."

To see if they could help heal some of this damage with stem cells, her team grafted engineered oligodendrocytes into various brain regions of 18 rats that had been treated with radiation.

They then tested their memory and learning skills, and also monitored the spread of the cells using imaging.

After 10 weeks, the rats that had received the new cells performed better than the control groups, with rats that had had the cells injected into their cerebellum, the region of the brain responsible for motor control, clearly better at balancing on a rotating pole.

The rats that had the cells grafted into their forebrains, on the other hand, were better at recognising a new object or realising when an object had been moved from their box. The animals that received the cells in both regions managed to get all of the learning and motor benefits.

"The cells were able to spread across most of the brain, integrate into the tissue, and add myelin to the nerves," said Jinghau Piao, who was involved in the study, in the release.

"And not only did the grafted oligodendrocytes repair the physical damage," added Tabar, "they also helped the rats improve a number of brain functions such as learning, memory, and balance."

The study, which has been published in Cell Stem Cell, also showed that the treatment appeared to be safe, although further testing is needed before it's trialled in humans. "No animals developed tumors or other complications as a result of the transplant, and the cells appeared to behave like natural oligodendrocytes," said Tabar.

Jonathan Glass, a neurologist at Emory University in the US, told Kate Baggaley from Science News that the breakthrough could have important therapeutic applications.

"This technique, translated to humans, could be a major step forward for the treatment of radiation-induced brain … injury," he said.

Source: Science News