History is full of medical procedures that could be considered more of an art than science.

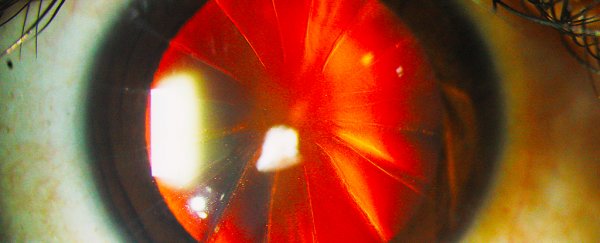

Take, for instance, the diverging lines radiating across the cornea of a 41 year old woman who presented to an ophthalmology clinic. The cuts are a legacy of a procedure that fortunately nobody risks anymore, making her eye an increasingly rare medical gem.

Known as a radial keratotomy, the incisions were made to change the shape of the cornea, refracting light in a way that intended to correct short-sightedness.

While the account of an unnamed patient in a recent medical case study is brief, it gives us a glimpse into an era of eye surgery before lasers came into medical fashion.

The procedure's development by pioneering Russian eye surgeon Svyatoslav Fyodorov, whether apocryphal or accurate, reads like a medical legend of discovery.

Fyodorov reports than he'd met with a young boy who suffered lacerations to his eye when a punch-up shattered his spectacles. After picking out the glass, the surgeon kept a careful watch over the boy's progress, and noticed not only did the eye heal, but its vision had improved dramatically.

The event inspired Fyodorov to try to correct the way light refracts through a cornea by applying his steady hand to a sharp scalpel and replicate the cuts he saw in the boy's eye.

By the 1970s, Fyodorov had discovered that a series of four, eight, 12, 16, or 32 radiating incisions could be scratched into a cornea in a way that overcame errors in bending light. Over the following decades, his radial keratotomy became a relatively popular way to correct myopia, allowing millions to ditch their glasses.

The Russian surgeon's work inspired other surgeons to try their hand. It's estimated that more than 8 million people underwent the procedure in the US and Canada alone, using diamond instruments and procedures devised by Fyodorov.

Yet even as the procedure exploded in popularity, not everybody was so enamoured with the operation's outcomes.

Reports surfaced showing heightened risks of infection and perforation. Results were inconsistent, unstable, and woefully short of amazing. Many who were nearsighted now found they were farsighted, forcing them to swap one optical prescription for another.

This was the case with the subject in this recent case study, whose sight had been deteriorating slowly ever since she'd undergone the procedure as a young adult. On closer examination, her ophthalmologists discovered the operation's distinctive lines, seen below against the normal crimson 'red-eye' backdrop of her retina.

(Tuteja & Ramappa, New England Journal of Medicine, 2019)

(Tuteja & Ramappa, New England Journal of Medicine, 2019)

Unfortunately there was little her tending physicians could do apart from providing her with a more appropriate prescription and advising her of the importance of wearing eye protection.

The good news is her increasing farsightedness has reportedly halted, based on a check-up six months later.

Today, laser surgery has overtaken radial keratotomies as a popular means of corrective treatment. Though not without its own risks, its success isn't as dependent on the artful dexterity of the surgeon.

Overall, the results of radial keratotomies were a mixed bag. A study conducted in the 1990s found that a decade after the procedure, a little more than half of the patients investigated had 20/20 vision or better. Only a third continued to wear glasses.

Fyodorov's generation of sliced-up eyes might be fading, but his work could be considered an important chapter in medical history books.

This research was published in the New England Journal of Medicine.