Every year in the US, up to 75,000 pregnant women undergo surgery under anaesthesia. How that affects the foetus is unclear - but new research has pinpointed a worrying possibility.

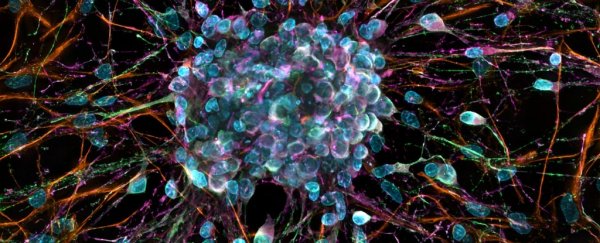

In a study on pregnant rats, a team of researchers found that anaesthesia seems to disrupt the migration of neurons in the foetus' brain, preventing them from arriving at their destinations in the cerebral cortex.

"The cerebral cortex, or grey matter, is the brain's computer processor," explained neuroscientist Vicko Gluncic of Rush University.

"Cognitive processes like thinking, memory, and language are directed there, thus neurons never reaching their proper and predetermined positions in the cortex may have a profound impact on brain function."

Previous studies had shown a strong correlation between prenatal or early-life exposure to anaesthetics and learning disabilities in humans, and behavioural abnormalities in animals, so Gluncic and colleagues sought to investigate why.

They injected 22 pregnant rats with a dye to tag the foetus' neurons, then anaesthetised them at the 16th or 17th day of gestation.

This a late stage of pregnancy for the rats, roughly equivalent to late in the second trimester for humans. It's also when the neuronal migration - when neurons move from their original position deep inside the brain to the outer region, or cerebral cortex - is at its most active.

A control group of rats was not anaesthetised, so the researchers could observe the differences in neuronal migration.

In the foetuses of the anaesthetised rats, a significant number of neurons remained scattered in the deeper levels of the cortex, instead of making it all the way out to the final position.

The longer the rats were anaesthetised, the more pronounced the scattering was. The control group did not have this scattering.

Then, after the baby rats were born, the researchers conducted behavioural studies. They found that the pups of anaesthetised mother rats had significant learning and cognitive deficits, compared to the control pups.

"There is a clear association of anaesthesia type and anaesthetic duration with neuronal migration and cognitive deficits at the drug levels used here (in rat fetuses)," said Rush University biostatistician Mario Moric.

"What is needed now is to further validate the mechanisms involved as well as test various anaesthetics and anaesthetic protocols to evaluate differential impact on cognitive functioning."

Although there is a clear association in rats, that doesn't necessarily mean the effect is exactly the same in humans, since animal models are not always predictive for human responses.

But the research does create a precedent that shows a need for further investigation into the effects of anaesthesia on the developing human foetus.

It also indicates that perhaps care should be taken when choosing the best time for a pregnant woman to undergo surgery.

Typically, non-urgent surgeries in pregnant women are performed in the second trimester, because that's after the foetus' organs have formed, and less likely to trigger contractions and miscarriage than the third trimester.

Obviously emergencies can't be helped, but maybe, according to this new research, this approach needs to be reconsidered for non-emergency surgery.

"Based upon the present data," Gluncic said, "the possibility that anaesthesia may affect fetal brain development should be seriously considered and disclosed in informed consent for anaesthesia in the second trimester since the most active period of human fetal brain development actually occurs between 12th and 24th week of pregnancy."

The research has been published in Cerebral Cortex.