A chance discovery during a hike in Grand Canyon National Park in 2016 ended up revealing strange footprints left by something that also walked there once, long, long ago.

So long ago, in fact, that these ancient tracks – left approximately 313 million years ago – represent the earliest footprints ever found in this epic, wondrous environment, according to a new study.

"These are by far the oldest vertebrate tracks in Grand Canyon, which is known for its abundant fossil tracks," says palaeontologist Stephen Rowland from the University of Nevada Las Vegas.

"More significantly, they are among the oldest tracks on Earth of shelled-egg-laying animals, such as reptiles, and the earliest evidence of vertebrate animals walking in sand dunes."

Artist's impression. (Emily Waldman)

Artist's impression. (Emily Waldman)

Not bad for a lucky find on a hiking trail. But the circumstances behind the discovery, made on a path called Bright Angel Trail, are even more serendipitous than they seem.

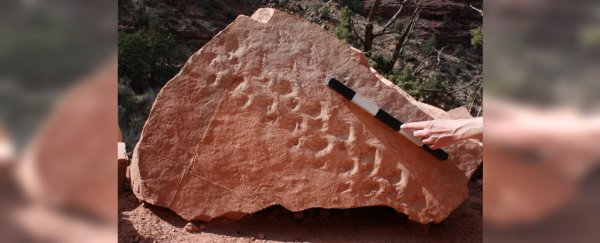

The fossil footprints in question were found on the side of a boulder that fell off a nearby cliff, exposing a stratigraphic cross section of the Manakacha Formation: a layer of ancient rock laid down approximately 315 million years ago.

In other words, if the cliff had never collapsed, the boulder would never have been encountered by hikers on the trial, and the ancient marks may have escaped notice for eternity.

Thanks to these chance events, however, researchers have now had the opportunity to analyse these very old trackways, and learn a bit about what kind of animal left them, back when this rocky surface was the slope of a sand dune.

Across the dune, two separate tracks can be seen, left by basal amniotes – very early specimens of tetrapod (four-limbed) vertebrates, and in this case, possibly from the base of the reptile evolutionary tree.

The first set of tracks reveal a distinctive, sideways-drifting pattern of footprints, interpreted as the trackmaker employing what's called a lateral-sequence gait, while diagonally ascending the dune slope.

In this kind of movement, the legs on one side of the animal move in succession before the legs on the other side do the same (left rear leg, left fore leg, right rear leg, right fore leg).

Lateral-sequence gait. (Rowland et al., PLOS ONE, 2020)

Lateral-sequence gait. (Rowland et al., PLOS ONE, 2020)

"Living species of tetrapods – dogs and cats, for example – routinely use a lateral-sequence gait when they walk slowly," says Rowland.

"The Bright Angel Trail tracks document the use of this gait very early in the history of vertebrate animals. We previously had no information about that."

Whether the gait was due to the steepness of the slope or the force of the wind is unclear, but the tracks, which are also the first tetrapod marks ever found in the Manakacha Formation, reveal that basal amniotes dwelled in sand dune regions even in this ancient era.

The second group of tracks are different, representing a later set of claw marks that suggest the animal (possibly the same species) was directly moving up the slope, rather than the diagonal ascent, sideways ascent of the first animal.

While it's impossible right now to determine exactly what kind of animal this was, the researchers say the marks bear a passing resemblance to Chelichnus – an ambiguous and debated set of fossil tracks found in Scotland, dating to the Permian period, and first mistaken for tortoise tracks.

Outside of these marks, it's possible this ancient species that once strode through the Grand Canyon, has never been discovered or detected in the fossil record.

"It absolutely could be that whoever was the trackmaker, his or her bones have never been recorded," Rowland said in 2018.

The findings are reported in PLOS ONE.