A scene painted on a cave wall more than 15,000 thousand years ago appears to tell the simple story of a hunter collapsing before a disembowelled beast. Reading between the lines, the images might describe something bigger. Maybe even astronomical.

Figures depicted in the famous prehistoric paintings at Lascaux were positioned with purpose, according to a fresh analysis of the artwork. These weren't mere stories about hunting. They were signs of the zodiac arranged to record a significant cataclysmic event.

Researchers from the Universities of Edinburgh and Kent compared zoomorphic artworks found at Neolithic sites around the world, from Göbekli Tepe and Çatalhöyük in Turkey to the caves near Montignac in southwestern France.

Depictions of familiar-looking animals, such as bulls, lions, and scorpions, aren't meant to represent familiar looking scenes, they argue. Instead, they could symbolise constellations, and as such represent an early form of astronomical record-keeping.

"Early cave art shows that people had advanced knowledge of the night sky within the last Ice Age," says one of the study's authors, chemical engineer Martin Sweatman from the University of Edinburgh.

If true, scenes drawn at Lascaux might instead mark the date of a major event that coincided with an annual Taurid meteor shower roughly 17,000 years ago.

Sound a little familiar? Last year the same researchers decoded stone carvings found at Göbekli Tepe as references to a comet strike thought to be responsible for a temporary return to Ice Age climate conditions around 13,000 years ago.

This new study takes their analysis a step further by applying it to other Neolithic art pieces from other sites and time periods.

Lascaux's paintings were discovered by a local group of teens in the 1940s, and we've been scratching our heads over them ever since. It's not clear exactly when they were created, but experts estimate the 600 images scattered over the walls are anywhere up to 17,000 years old.

Many of the figures are of animals that would have lived within the local region, including horses and bison-like animals called aurochs.

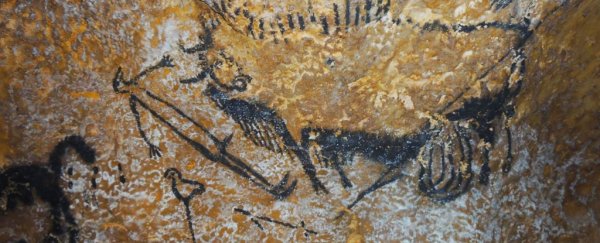

The images known collectively as the Shaft Scene include a human figure angled next to an auroch, which has loops of its intestines dangling from its belly.

Nearby there is something that looks a bit like a duck, while a rhinoceros looks away to the left. A horse head is sketched on another section of the wall.

We can all take guesses at why somebody would go to the trouble of crawling inside a cave to awkwardly inscribe a man toppling over in front of a gutted animal while a bird creepily watches on and a rhino pretends not to notice … and plenty of historians have their opinions.

Caves are considered to be supernatural places linked with deities and the like, so it's possible these images were drawn seeking godly favour before a hunt, like a prehistoric wish-list or a form of prayer.

But other researchers have noticed the proximity of various animals around the caves seems to be less than random. The French anthropologist André Leroi-Gourhan figured back in the 1960s that this represented some sort of classification system, of good and evil or male and female.

There are also geometric shapes, dots, and odd lines scattered throughout the images, and which are hard to account for if they were attempts to realistically draw natural settings.

The idea that they could somehow reflect not pastoral scenes but celestial ones has been discussed for more than 40 years.

Sweatman and his colleague from the University of Kent, Alistair Coombs, now argue this is the right approach, and that we should give our ancestors more credit when it comes to representing the world.

"Intellectually, they were hardly any different to us today," says Sweatman.

Like Göbekli Tepe's Vulture Stone, the Shaft Scene shows a human figure who seems to be dying, near four prominent animals.

The researchers argue the injured bison represents the constellation Capricorn at summer equinox, and the bird stands in for Libra at spring equinox. The other animals are more speculative, but could easily match Leo and Taurus at the other equinoxes.

This arrangement could mark a date of 15,150 BCE, give or take a couple of centuries, hinting at an event that may have impacted humans in a less than pleasant way.

Records taken from Greenland's ice cores do suggest the climate began to shift around 15,300 BCE, but there are no signs that this was caused by some sort of meteorite impact.

We've been carving and painting animals for tens of thousands of years, and it's not always clear why we do it.

The 40,000-year-old carving of an upright lion found in the Hohlenstein cave in Germany is another odd-ball example that's come to the attention of Sweatman and Coombs.

"These findings support a theory of multiple comet impacts over the course of human development, and will probably revolutionise how prehistoric populations are seen," says Sweatman.

No doubt historians will continue to argue over the meaning of ancient art for a long time to come.

If anything, these findings show we might need to move on from strictly shamanistic interpretations, to see art as integral to marking time based on a bold feature of the environment we often overlook in our modern world – the night sky.

This research was published in the Athens Journal of History.