A new look at an extremely rare infant burial in Europe suggests humans were carrying around their young in slings as far back as 10,000 years ago.

The findings add weight to the idea that baby carriers were widely used in prehistoric times, although archaeological evidence of such cloth is not usually preserved in the fossil record.

Researchers discovered the grave in Italy's Arma Veirana cave in 2017. In the years since, the buried infant was dubbed "Neve", and her teeth suggest she is the oldest female child interred in Europe.

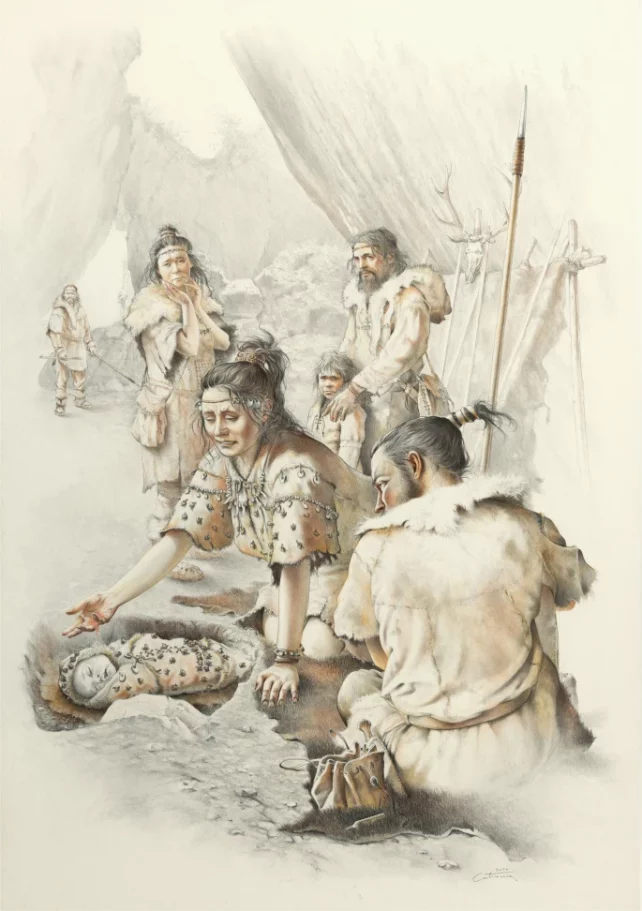

Notably, Neve's community laid her to rest with a large number of beads, suggesting she was well-loved and well-regarded.

Now, a fresh analysis of the grave's contents and the child's position suggests adults carried Neve during her short life, wrapped in a shell-adorned sling.

Nothing remains of the wrap today, but the shells surrounding Neve are perforated in such a way that indicates someone strung the shells together and sewed them on textile, fur, or hide.

A previous 2017 study of Neve's beads estimated they took hours of work to fashion. Burying the ornaments would not have been a decision made lightly.

These materials could have formed a sling, or they could have been a blanket or undergarment.

All three theories are legitimate, but researchers behind this latest analysis, led by Arizona State University anthropologist Claudine Gravel-Miguel, suspect the baby carrier option is more likely for a few reasons.

Because the infant's legs are tucked up over the abdomen, disguising many of the shells, Gravel-Miguel and colleagues suspect these adornments were not meant as funerary ornaments, scattered on the top of a grave.

Instead, they were probably "part of a decorated garment or baby sling that was likely used during the infant's life."

Some of the shell beads are even curved around the child's upper arm bone, possibly tracing the outline of the long-lost wrap.

Careful scanning of the shells themselves shows they are well-worn, and suggests they were used for much longer than this child's short 40- to 50-day life.

"The results of the study suggest that the beads were worn by members of the infant's community for a considerable period before they were sewn onto a sling, possibly used to keep the infant close to the parents while allowing their mobility, as seen in some modern forager groups," the authors surmise.

Other burial sites on the Italian peninsula rarely encompass more than 40 perforated shells a piece, and yet Neve is buried with more than 70 along with four perforated bivalve pendants, seemingly unique to this site.

The abundance of sea shells buried with Neve has allowed researchers to identify potential patterns of ornament use, in relation to the child's posture.

Other recent studies on prehistoric infant burial sites have also found potential ornaments that look as though they were attached to fixed objects, like blankets or baby carriers. They are usually too large to have been worn by the children themselves, researchers suspect.

Ancient human ornaments on clothing are usually thought to communicate identity, gender, and status, but they could also be a form of spiritual protection.

A modern Indigenous community in the Amazon, for instance, uses decorations and ornaments as representations of parental care toward their offspring.

"The baby was then likely buried in this sling to avoid reusing the beads that had failed to protect her or simply to create a lasting connection between the deceased infant and her community," the authors write.

In other modern forager populations, similar decorations are still sewn on baby carriers and slings to this day.

"Not surprisingly, in those societies, infants and children are always well adorned. Among the beads that are used to decorate and protect their bodies, the majority are 'second-hand' items, i.e., beads that have been donated by the parents, grandparents, and relatives as an act of care toward the child," the authors of the new study write.

"This paper contributes truly original information on the archaeology of childcare," says anthrolpologist Julien Riel-Salvatore from the University of Montreal.

"It bridges the science and art of archaeology to get to the 'human' element that drives the kind of research we do."

The study was published in the Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory.