New analysis on a wooden sculpture discovered more than 100 years ago shows it's much older than previously thought – and could be one of the earliest relics we have showing the face of an evil spiritual force.

The 5-metre (16.4-foot) long idol, originally pulled from a peat bog near the Russian city of Yekaterinburg in 1894, is now said to be some 11,000 years old. For context, that's twice as old as the Great Pyramids of Egypt.

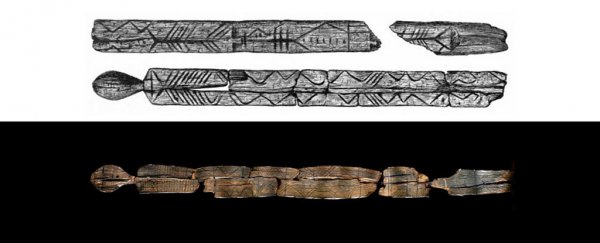

What's more, as well as recalculating the date of the artefact, the study has identified an extra face along the body of the wood, alongside several others and a human-like visage on top. These could represent evil spirits or demons, the researchers say.

Attaching a new date to the statue potentially changes the view of historians on how this kind of art originally began – it's significantly different to the more naturalistic images of the ice age, and at 11,000 years old, would have been carved out by hunter-gatherers rather than the farmers who followed in this part of the world.

"We have to conclude hunter-gatherers had complex ritual and expression of ideas," one of the researchers, archaeologist Thomas Terberger from the University of Göttingen in Germany, told Andrew Curry at Science.

"Ritual doesn't start with farming, but with hunter-gatherers."

Researchers were able to get a better fix on the date of the sculpture by taking samples from deeper inside the wood, beneath attempts to preserve the statue with some kind of glue or preservative.

These samples were then put through an Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS) dating process, a type of radiocarbon dating analysing the decay of carbon atoms through a blast of charged ions.

(Antiquity)

(Antiquity)

An antler carving also discovered near the same spot has been dated to a similar period, backing up the new timeline.

Putting the idol in the Early Holocene period means it would have been made as Eurasia was warming up, and forests were advancing as ice retreated. It looks like art was changing too – similar designs have been found in Turkey, also dating from the same time.

"Figurative art in the Paleolithic and naturalistic animals painted in caves and carved in rock all stop at the end of the ice age," archaeologist Peter Vang Petersen from the National Museum of Denmark, who wasn't involved in the study, told Science.

"From then on, you have very stylised patterns that are hard to interpret. They're still hunters, but they had another view of the world."

The statue may well have been used for rituals or even to warn people away from certain areas, the researchers suggest, which is where the idea of evil spirits comes from. A total of seven faces have been found on the object, some of them very well concealed in the artwork running down the wood.

Another possibility is that they're like the totem poles of the Pacific Northwest, designed to honour gods or remember ancestors, although it's hard to be sure.

What's more certain is that this kind of art was being developed further back and in more places than we previously thought. That should help both art historians and those looking for traces of activity of the earliest human beings, the researchers say.

"Such a big sculpture was well visible for the hunter-gatherer community and might have been important to demonstrate their ancestry," Terberger told Laura Geggel at Live Science. "It is also possible that it was connected to specific myths and gods, but this is difficult to prove."

The statue is on show at the Sverdlovsk Regional Museum in Yekaterinburg, and the latest research on it has been published in Antiquity.