In the charcoaled remains of fires that smoldered more than 10,000 years ago, archaeologists have found evidence of what may be the longest continuing ritual – shared across generations of Indigenous Australians since the end of the last ice age to this day.

The ancestral lands of the GunaiKurnai Aboriginal people lie in the foothills of the Australian Alps, an alpine area in southeastern Australia dotted with rock boulders and limestone caves, and extend southwest to the Victorian coast.

These caves weren't used by the GunaiKurnai people for shelter, but as secluded retreats for magic practitioners known as mulla-mullung. Ethnographers documented these practices in the 1800s but archaeologists inspecting the caves in the 1970s overlooked them because magic rituals didn't fit with their mainly secular interpretations of the caves as places to cook and sleep.

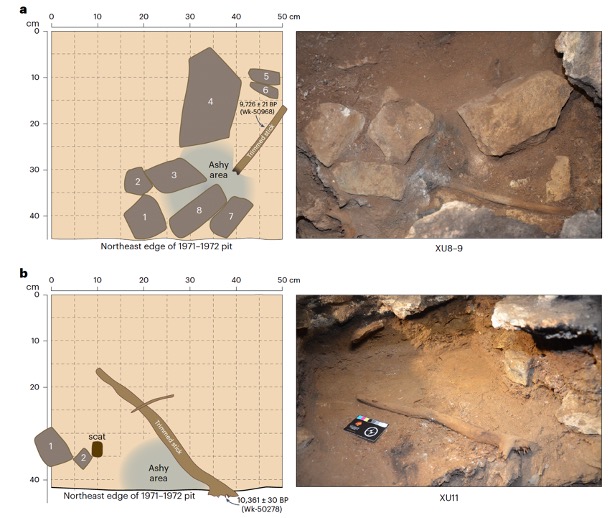

Now, a team of archeologists working with the GunaiKurnai people have unearthed and described two miniature fireplaces ringed by limestone rocks and each containing a single stick of Casuarina wood stripped of side branches and smeared with fatty tissue.

Ethnographic accounts from Australia in the 19th century describe these rituals, conducted in caves by an esteemed "doctor" away from the rest of the community. Some European accounts describe the role as one who "betwitched" or "healed … of bewitching", describing objects lopped from or touched by an intended victim that were attached to a piece of wood and burnt briefly with some human or animal fat.

Monash University archaeologist Bruno David, GunaiKurnai Elder Russell Mullett and their colleagues have now uncovered evidence of this practice, deep within Cloggs Cave.

The fireplaces inside the cave are thought to have been rapidly buried soon after they were last used, by sediments that date back some 10,000-12,000 years, to the end of the last ice age and the dawn of the Holocene, our current geological epoch. What's more, the two fireplaces are nearly identical, yet the team's dating suggests they were built and used 1,000 years apart.

Excavated in 2020 with the permission and help of GunaiKurnai Aboriginal Elders, the fireplaces and the wooden implements – which would have decayed had they been exposed – have been preserved out of sight for millennia.

This makes it unlikely that abandoned remains of the ritual could have been seen and copied by naive newcomers to the cave, supporting claims the GunaiKurnai people's traditions have been orally shared for at least 10,000 years.

"The suite of factors contributing to the survival of both [fireplaces] and their wooden artifacts provides unparalleled insight into the resilience of GunaiKurnai narrative traditions," David and his colleagues write in their published paper.

"These findings are not about the memory of ancestral practices, but of the passing down of knowledge in virtually unchanged form, from one generation to the next, over some 500 generations."

After centuries of colonial dispossession and dismissal, archeologists (and other scientists) are beginning to learn from and work more respectfully with Australia's First Nations peoples, integrating their traditional knowledge into scientific analyses to enrich and strengthen the findings.

These analyses, often of genetic histories, confirm what Indigenous peoples have known all along and continued to assert through oral traditions: that they maintain deep connections to their ancestral lands.

In Australia specifically, researchers have matched ancient creation stories telling of the Gunditjmara people's ancestors being borne out of volcanic eruptions to geological records of those same events.

Similarly, oral traditions of the Palawa people of Tasmania tell of rising seas that flooded the land bridge connecting the island to mainland Australia some 12,000 years ago, and of constellations that lit up the night sky at that time.

This new work involving the GunaiKurnai people differs slightly in that the team has uncovered delicate handmade remnants of ritual practices, preserved like the oral traditions themselves.

The study has been published in Nature Human Behaviour.