More than 72 million years ago, the western seas of the Pacific Ocean were home to one of the fiercest ocean predators of all time.

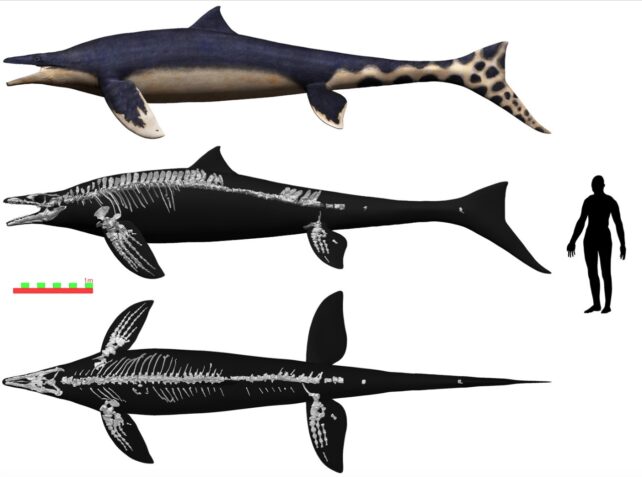

About the size of a bus, the colossal air-breathing creature wasn't a mammal despite its warm-blood. Nor was it a crocodile despite its similar shaped head. Instead it belonged to a group of now extinct marine lizards, ones with binocular vision, four enormous paddle-shaped limbs, a long and powerful rudder of a tail, and possibly a dorsal fin.

Scientists in Japan are calling it the Wakayama 'blue dragon', for the place it was found and the mythic creatures of Japanese folklore.

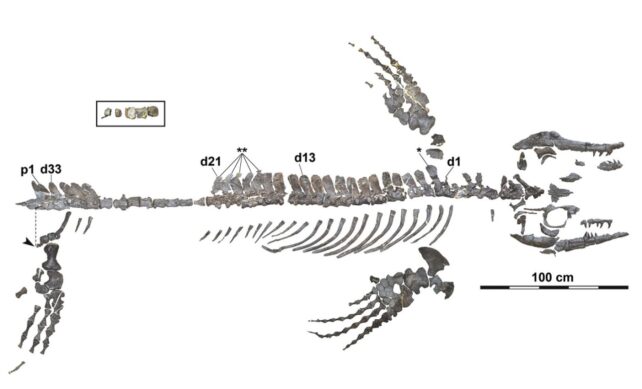

A nearly complete skeleton of the extinct animal was originally discovered in 2006 along the Aridagawa River in Wakayama by paleontologist Akihiro Misaki from the Kitakyushu Museum of Natural History and Human History. It took five careful years of work to remove the bones from the stone they were buried in.

A formal description of the 6-meter-long creature has now classified it as a whole new species of mosasaur, called Megapterygius wakayamaensis.

Figuring out how it swam or hunted is proving quite the challenge.

"We lack any modern analog that has this kind of body morphology – from fish to penguins to sea turtles," says palaeontologist Takuya Konishi from the University of Cincinnati. "None has four large flippers they use in conjunction with a tail fin."

Mosasaurs were some of the greatest predators of all time, stretching up to 17 meters in some cases. For some 20 million years, these fearsome beasts reigned supreme in the ocean, the last of the great marine lizards.

Their crushing jaws and cutting teeth could take on just about anything, from shellfish to turtles to sharks. They even ate others of their kind.

Konishi, an expert on the monstrous marine lizards, thought he understood mosasaurs until he laid his eyes on the Wakayama blue dragon.

Its paddle-shaped flippers, especially its back ones, are unusually long compared to other mosasaur fossils found elsewhere in the world, like New Zealand, California, and Morocco.

The spines on its vertebrae also look different, almost dolphin- or porpoise-like.

Cetaceans like dolphins and porpoises have dorsal fins just to the back of their center of gravity, which provides additional stability while swimming.

While still quite hypothetical, the scientists working on M. wakayamaensis think this mosasaur may have had a dorsal fin, too.

Based on the fact that cetaceans with longer flippers use the limbs to maneuver while swimming rather than just cruising, the team in Japan speculate that the Wakayama blue dragon used its front fins for similar reasons.

Its back fins, which modern cetaceans don't have, may have been used to help it dive or surface.

Its tail would have probably been the propulsive factor.

By comparison, plesiosaurs, which were ancient swimming reptiles that lived alongside mosasaurs, used their flippers rather than their tails for thrust.

Scientists think most plesiosaurs couldn't compete with mosasaurs as predators, but whether that had to do with their different swimming abilities is uncertain.

"It's a question just how all five of these hydrodynamic surfaces were used. Which were for steering? Which for propulsion?" explains Konishi.

"It opens a whole can of worms that challenges our understanding of how mosasaurs swim."

The study was published in the Journal of Systematic Palaeontology.