Bones bearing signs of cancer found in an ancient Egyptian cemetery reveal that the often devastating disease is much more prevalent now than it was in the people who lived near the Dakhleh Oasis.

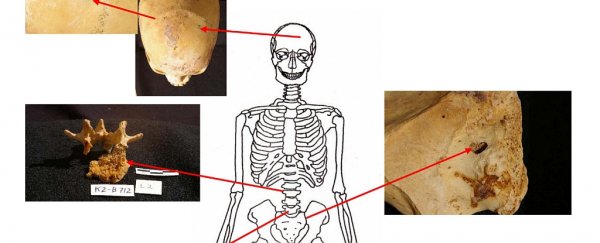

Out of 1,087 skeletons buried between 1,500 and 3,000 years ago, just 6 were found with cancer - two younger women with cervical cancer, and a man with testicular cancer, which have all been associated with HPV; and an older mummified man with colorectal cancer, an older woman with metastatic carcinoma, and a toddler with leukaemia.

That's a rate of 5 cases in 1,000 - compared to today, where the cancer rate in Western societies approaches 500 per 1,000 people - a lifetime cancer risk 100 times greater than what it was in the ancient Dakhleh in Egypt's Western Desert.

Because soft tissue doesn't often survive millennia, the researchers looked for the traces cancer leaves on bone.

Lesions found on the skeletons were consistent with carcinoma, and, although it's difficult to diagnose based simply on bones, the researchers were able to determine the most likely types based on the distribution and types of legion, as well as the age and sex of the person.

Three of them - two women and a man - fell outside the normal age range, dying in their 20s and 30s.

"When the Dakhleh cases were first presented at professional meetings a common comment against accepting the diagnosis of cancer was that 'their ages were too young'!" the researchers, anthropologist El Molto of The University of Western Ontario and Ontario physician Peter Sheldrick, wrote in their paper.

But the 25-30-year-old male was likely afflicted with testicular cancer, since that age is the highest risk group, and the two young women were most likely afflicted by cervical cancer.

Both of these types of cancer are linked with HPV, recent research has found (although its implication in testicular cancer is rare) - and HPV has been around for a very long time, much longer than the age of the bones.

And all strains of the virus evolved in Africa.

"The two female and the male burials from Dakhleh, all young adults, could have respectively developed cancer of the uterine cervix and testicular cancer," Molto and Sheldrick wrote.

"We know from current cancer epidemiology research that both types of cancers peak in the young adult cohorts and the HPV risk factor would have likely been present the paleoecology of ancient Dakhleh."

Interestingly, the older male mummy had soft tissue preserved, including a tumour. This meant that a full autopsy and tissue analysis could be performed, positively identifying rectal adenocarcinoma.

The older woman most likely had ovarian, breast, or colorectal cancer; and the child, in whom almost every single bone showed signs of a systemic disease, probably had acute leukaemia, given its prevalence among that age group.

There are some caveats guiding estimates of the prevalence of cancer in ancient Egypt. Firstly, the average lifespan was shorter - only 7.7 percent of the ancient Dakhlans were estimated to be over 60 years of age, the researchers said.

Given that a quarter of new cancer cases are diagnosed between the ages of 65 and 74, according to the US National Cancer Council, this shorter lifespan could impact lifetime cancer risk.

Another factor that could affect results is the relative lack of soft tissue. Cancer doesn't always leave a mark on bones, so there could have been some cases among the 1,087 skeletons that the researchers missed.

Even accounting for these caveats, however, Molto and Sheldrick believe that the prevalence of cancer was still at least 50 times lower in ancient Dakhleh.

"In our opinion, it is doubtful that even if the ancient Dakhlans had the same life expectancy as modern western societies the rate of cancer would have been equivalent," they wrote in their paper.

"The carcinogenic load in their past environments would have been considerably less carcinogenic than modern western societies."

The research has been published in the International Journal of Paleopathology.