The ancient Egyptians were remarkably sophisticated and advanced in the field of medicine – so noted for their skills and knowledge that we're still learning from them, thousands of years later.

But there were some things that the Egyptians struggled to treat. One of those should come as no surprise, since it still represents a significant challenge, even today. That, of course, is cancer – the mutation of living tissue into something malignant and deadly.

Nevertheless, we have new evidence that the ancient Egyptians did not take cancer lying down. Two skulls currently housed in the University of Cambridge's Duckworth Collection show evidence of cancer and other injury – and signs of attempts to treat them.

"This finding is unique evidence of how ancient Egyptian medicine would have tried to deal with or explore cancer more than 4,000 years ago," says paleopathologist Edgard Camarós of the University of Santiago de Compostela in Spain. "This is an extraordinary new perspective in our understanding of the history of medicine."

The two skulls both show signs of cancer – but each, after careful microscopic and CT scan analysis, tells a very different story.

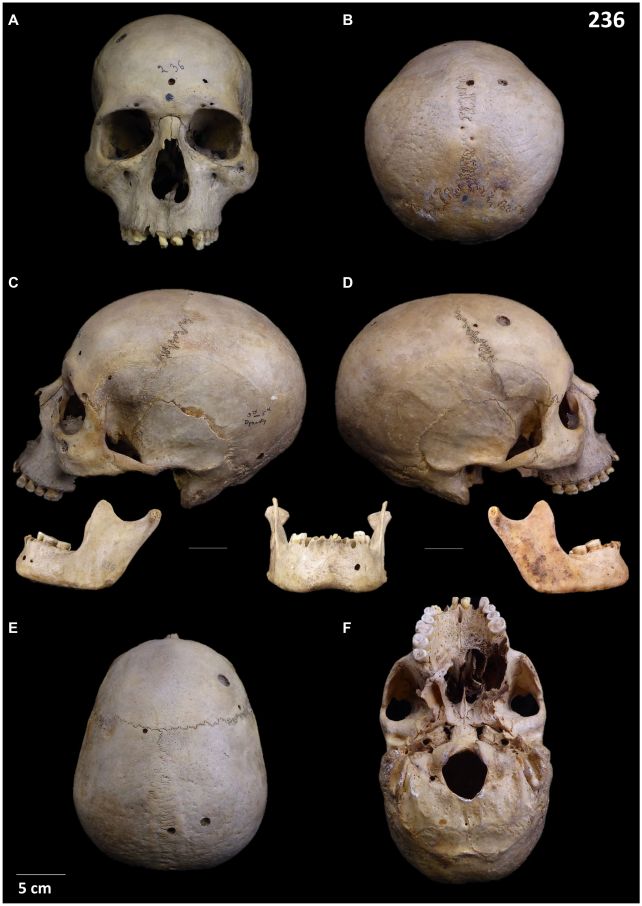

Skull number 236 belonged to a male individual who lived in ancient Egypt sometime between 2687 and 2345 BCE. He died in his early 30s, and his skull is riddled with around 30 lesions, consistent with metastasized carcinoma, although there are other possible diagnoses.

Most of these lesions are relatively small, but there are some noticeably larger ones, including a coin-sized divot hollowed out as tissue was destroyed by cancerous tissue, or a neoplasm, on the top of the man's skull.

When the researchers took a closer look at the lesions, they noticed something extraordinary. The edges are scored with cut marks, as though an ancient surgeon had attempted to remove the neoplasms using a metal implement. These cut marks show little to no sign of healing, indicating that they occurred around the time of death – perhaps forensically, perhaps as a last resort, but almost certainly to do with the man's cancer.

"It seems ancient Egyptians performed some kind of surgical intervention related to the presence of cancerous cells," says orthopedic surgeon Albert Isidro of the University Hospital Sagrat Cor, "proving that ancient Egyptian medicine was also conducting experimental treatments or medical explorations in relation to cancer."

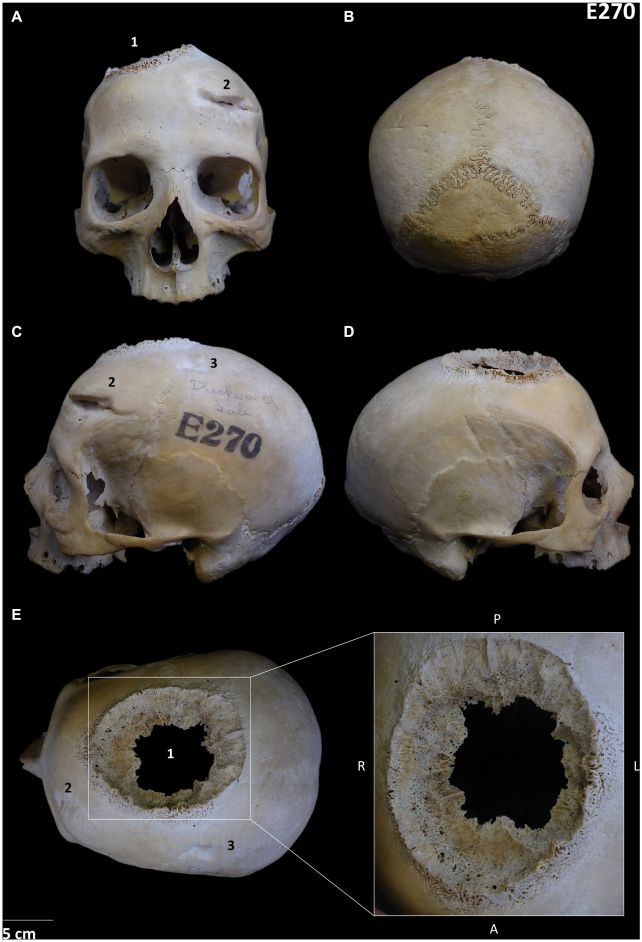

Skull number E270 in the Duckworth Collection belonged to a female individual who lived between 663 and 343 BCE. She was over 50 when she died, and her skull is full of story. What you might notice first is a huge lesion dominating the top of the skull between the right frontal and parietal bones. This lesion is consistent with osteosarcoma or meningioma, among other potential diagnoses.

But there are other marks on the skull that are healed. Over her left eyebrow is a large injury created by sharp-force trauma. Someone, the researchers say, seems to have whacked her in the head with a sharp weapon. And a little further back on the left side of the top of her head is an injury caused by blunt-force trauma.

What makes these injuries really interesting is that they're very well healed. We don't know if they were sustained at the same time or separately, but she survived both – again suggesting that she may have received treatment. But the very fact of the wounds, so very warlike, is a puzzle on a female victim.

"Was this female individual involved in any kind of warfare activities?" says archaeologist Tatiana Tondini of the University of Tübingen in Germany. "If so, we must rethink the role of women in the past and how they took active part in conflicts during antiquity."

The huge cancerous lesion on the woman's skull, by contrast with the man's skull and her earlier injuries, shows no sign of treatment that we can confidently identify.

So, while the cause of death for both patients cannot be clearly established, the advanced state of the cancer in both cases indicates a link to mortality that cannot be ignored. Although the treatment attempt was made by the ancient Egyptians, the cure seems to have remained elusive.

"We wanted to learn about the role of cancer in the past, how prevalent this disease was in antiquity, and how ancient societies interacted with this pathology," Tondini says. "We see that although ancient Egyptians were able to deal with complex cranial fractures, cancer was still a medical knowledge frontier."

The findings have been published in Frontiers in Medicine.