They say a tree never forgets, and apparently, neither does its resin. For more than ten thousand years, an ancient chewing gum, made from the tar of a birch bark tree, has held the memory of Scandinavia's first human settlers.

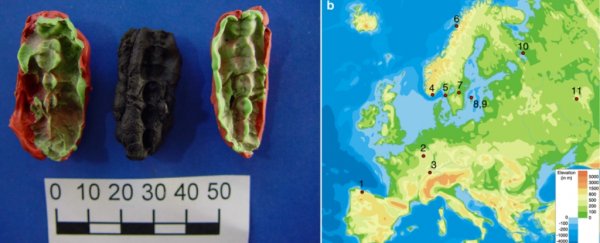

Discovered in the 1990s, in a prehistoric hunter-fisher site on the Swedish coast, known as the Huseby Klev, the three pieces of roughed-up gum spent decades without scientists ever looking for their secrets.

A few years ago, researchers at last began testing the fragile material, and in December of last year, a pre-printed study claimed to have found ancient human DNA in the remains. Now, five months later, the team has published an updated, peer-reviewed paper, and it's every bit as juicy as a used piece of gum.

"It took some work before the results overwhelmed us, as we understood that we stumbled into this almost 'forensic research', sequencing DNA from these mastic lumps, which were spat out at the site some 10,000 years ago!" says co-author Natalija Kashuba, who was affiliated with The Museum of Cultural History in Oslo at the time of research.

Mashed up into the tooth-marked lumps, the team found remnants of Stone Age saliva. And from this they were able to sequence the oldest human DNA from this area.

Each lump, it seems, belonged to one individual: two females and one male. But unlike today, this was not just a hobby, the authors say. Surrounded by the shavings of raw material, the site was likely used for tool-making, and the sticky gum was part of the process.

"The material we use is made of birch bark pitch, which is known to have been used as an adhesive substance in lithic tool technology from the Middle Palaeolithic onward in many parts of Eurasia," the authors explain, "but also for recreational purposes, and as a cement for mending and sealing wood and ceramic vessels."

For the first time, the authors were able to link the tools these early humans produced to an ancient technology, brought to Sweden from Eastern Europe, or what is now modern day Russia.

Yet combing through genomic data, the authors show that these early humans were actually more genetically similar to western hunter-gatherers and individuals from Ice Age Europe.

In other words, both the site and these humans seem to be sitting right where the currents of western and eastern migration once collided.

"This scenario of a culture and genetic influx into Scandinavia from two routes was proposed in earlier studies, and these ancient chewing gums provides an exciting link directly between the tools and materials used and human genetics," says co-author Emrah Kirdök from Stockholm University, who conducted the computational analyses of the DNA.

They can also tell us quite a lot about the cultural history of the region. For instance, because the gum was connected to tool-making and maintenance, the authors think we might need to update our understanding of gender roles in Mesolithic societies.

"Combined with the fact that several mastics from the site have imprints of deciduous teeth, the new information allows us to discuss gender in childhood," the authors continue.

"The possible interpretations are that tool-production was not restricted to one sex, or, if the individuals examined were children, that gender roles did not yet apply to young individuals."

In a world where human bones and tools rarely survive the ages, perhaps there are other tree remnants out there that hold similar secrets.

"DNA from these ancient chewing gums have an enormous potential not only for tracing the origin and movement of peoples long time ago, but also for providing insights in their social relations, diseases and food," says co-lead author Per Persson, a blank from the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo.

This study has been published in Communications Biology.