Archaic humans may have worked out how to sail across the sea to new lands as far back as nearly half a million years ago.

According to a new analysis of shorelines during the mid-Chibanian age, there's no other way these ancient hominins could have reached what we now call the Aegean Islands. Yet archaeologists have found ancient artifacts on the islands that pre-date the earliest known appearance of Homo sapiens.

This suggests that these ancient humans must have found a way to traverse large bodies of water. And if reliance on land bridges was not necessary for human migration, it may have implications for the way our ancestors and modern humans spread throughout the world.

The question of when hominins began sea-faring is difficult to answer. Boats throughout history tend to be made of wood, a material that doesn't often survive the ravages of time intact – and certainly not for tens of thousands, never mind hundreds of thousands of years. So there's no hope of a record of the first boats skimming across the oceans.

Instead, what we have is a record of artifacts and bones that have survived – stone tools that don't decay, for instance – and analysis tools that allow us to reconstruct the way the world has changed over many millennia. Led by geologist George Ferentinos of the University of Patras in Greece, this is how a team of researchers were able to conduct the new analysis.

The islands of the Aegean are, today, considered among the world's most beautiful places. They consist of hundreds of islands making up an archipelago scattered across the Aegean Sea between Turkey, Greece, and Crete. And they've been inhabited for a long time; artifacts have been dated to potentially as early as 476,000 years ago.

These ancient tools on Lesbos, Milos, and Naxos, moreover, have been linked to the Acheulean style developed some 1.76 million years ago, associated with Homo erectus across Africa and Asia. Several such tools have been found in Turkey, Greece, and Crete dating back to 1.2 million years ago, so their appearance in the nearby archipelago does make some sense.

Previous studies suggested that ancient humans crossed to the islands on foot during ice ages. When the world freezes, the sea level drops, and humans can make crossings that would be covered by water in more temperate times.

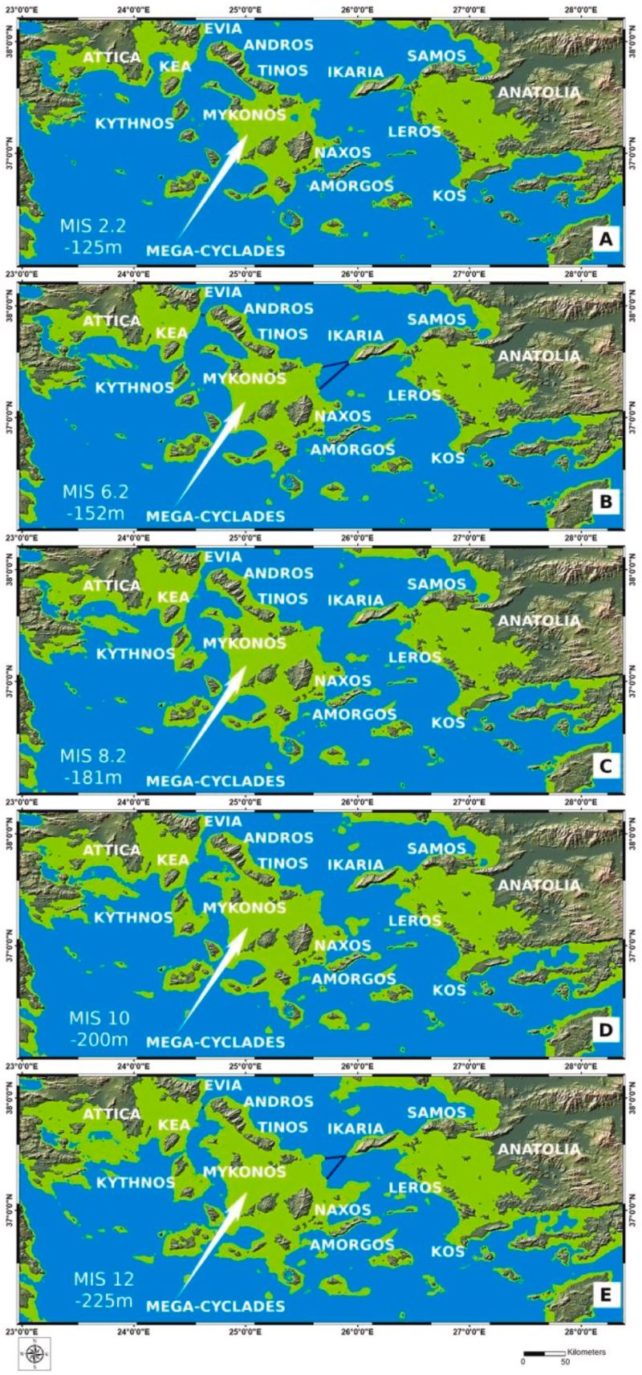

To determine whether this is a possibility, Ferentinos and his colleagues reconstructed the geography of the region, including a reconstruction of the shoreline around the Aegean Islands dating back to 450,000 years ago. For this, they used ancient river deltas, which can be used to infer sea level, and rates of subsidence driven by tectonic activity.

And they found that previous reconstructions were incorrect. At its lowest point over the last 450,000 years, the sea level was approximately 225 meters (738 feet) lower than it is today.

This means that, while some of the Aegean Islands were connected to each other when sea levels were lower, over the last 450,000 years, the islands have remained consistently insular from the surrounding land masses. At the sea level's lowest point, there still would have been several kilometers of open water to traverse to reach the nearest of the Aegean Islands.

Other evidence, the researchers point out, suggests that this was not the earliest sea crossing. Sometime between 700,000 and a million years ago, archaic humans were thought to have been traveling the sea around Indonesia and the Philippines.

These combined crossings suggest that sea travel was a skill developed not by Homo sapiens, but the human ancestors and relatives that came before.

"Furthermore, considering that the archaic hominins were able to cross the Aegean Sea, they would also have been capable of crossing the Gibraltar Straits," the researchers write in their paper.

"The above mentioned allow us to revise the generally accepted view on the peopling of southwestern Europe from the Sinai Peninsula and Levantine plains staging post via the Anatolia coastal zone and the Bosporus land-bridge in the mid and late Middle Pleistocene, based on the consensus that sea-crossing cognitive abilities were restricted to anatomically modern humans."

The research has been published in Quaternary International.