The remains of a giant, ancient lake have been discovered under Greenland, buried deep below the ice sheet in the northwest of the country and estimated to be hundreds of thousands of years old, if not millions, scientists say.

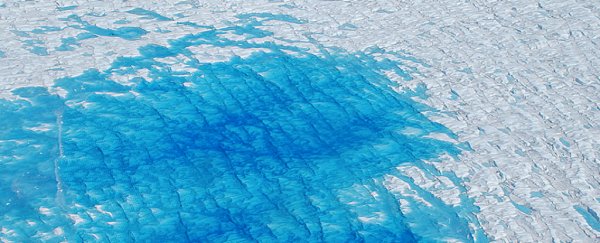

The huge 'fossil lake bed' is a phenomenon the likes of which scientists haven't seen before in this part of the world, even though we know the colossal Greenland Ice Sheet (the world's second largest, after Antarctica's) remains full of mysteries hidden under its frozen lid while shedding mass at an alarming pace.

Last year, scientists reported the discovery of over 50 subglacial lakes beneath the Greenland Ice Sheet: bodies of thawed liquid water trapped between bedrock and the ice sheet overhead.

The new find is of a different nature: an ancient lake basin, long dry and now full of eons of sedimentary infill – loose rock measuring up to 1.2 kilometres (three-quarters of a mile) thick – and then covered by another 1.8 kilometres of ice.

(Columbia University, adapted from Paxman et al., EPSL, 2020)

Above: The lake basin (red outline), fed by ancient streams (blue).

When the lake formed long ago, however, the region would have been free of ice, researchers say, and the basin would have supported a monumental lake with a sprawling surface area of approximately 7,100 square kilometres (2,741 square miles).

That's about the same size as the combined area of US states Delaware and Rhode Island, and this massive lake would have held around 580 cubic kilometres (139 cubic miles) of water, being fed by a network of at least 18 ancient streams that once existed to the north of the lake bed, flowing into it along a sloping escarpment.

While there's no way of knowing right now just how ancient this lake is (or if it filled and drained numerous times), we might be able to find out if we could analyse the loose rock material now inside the basin: a giant time capsule of preserved sediment that could give us some clues about the environment of Greenland roughly forever ago.

"This could be an important repository of information, in a landscape that right now is totally concealed and inaccessible," says lead researcher and glacial geophysicist Guy Paxman from Columbia University.

"If we could get at those sediments, they could tell us when the ice was present or absent."

The giant lake bed – dubbed 'Camp Century Basin', in reference to a nearby historic military research base – was identified via observations from NASA's Operation IceBridge mission, an airborne survey of the world's polar regions.

During flights over the Greenland Ice Sheet, the team mapped the subglacial geomorphology under the ice using a range of instruments measuring radar, gravity and magnetic data. The readings revealed the outline of the giant loose mass of sedimentary infill, composed of less dense and less magnetic material than the harder rock surrounding the mass.

It's possible, the team thinks, that the lake formed in warmer times as a result of bedrock displacement due to a fault line underneath, which is now dormant. Alternatively, glacial erosions might have carved the shape of the basin over time.

In either case, the researchers believe the ancient basin could hold an important sedimentary record, and if we can somehow drill down deep enough to extract and analyse it, it may indicate when the region was ice-free or ice-covered, reveal constraints of the extent of the Greenland Ice Sheet, and offer insights into past climate and environmental conditions in the region.

Whatever secrets those deeply buried rocks can tell us about polar climate change in the ancient past could be vital information for interpreting what's happening in the world right now.

"We're working to try and understand how the Greenland ice sheet has behaved in the past," says Paxman. "It's important if we want to understand how it will behave in future decades."

The findings are reported in Earth and Planetary Science Letters.