There's a problem for researchers trying to identify the size of ancient armored fish from the late Devonian period (approximately 382-358 million years ago): only the armored parts around their heads have been preserved in fossils.

In other words, we've been trying to judge the size of species like those in the Dunkleosteus genus of large underwater creatures based on the size of their mouth and jaws. The rest of the body, made up of cartilage, hasn't survived down the millennia.

A new analysis of data from previous studies suggests that the dimensions of these prehistoric fish cannot be judged based on the size of modern-day sharks, which is one of the methods that has been used to try and fill in the gaps in scientific knowledge.

"Length estimates of 5 to 10 meters [16.4 to 32.8 feet] have been cited for Dunkleosteus for years," says paleontology graduate student Russell Engelman from Case Western Reserve University in Ohio. "But no one seems to have checked these methods statistically or tested if they produce reliable or reasonable results in arthrodires."

Looking again at the data from four Dunkleosteus fossils and hundreds of living fish species, particularly in terms of the relationship between internal and external mouth measurements and overall size, Engelman found that the earlier estimates were probably wide of the mark.

If the prehistoric fish had been as big as previously thought, it would've had an unusually elongated body compared to its head – with proportions even greater than modern-day eels, for example. What's more, the calculated size of the gills would've probably been too small for the fish to breathe properly.

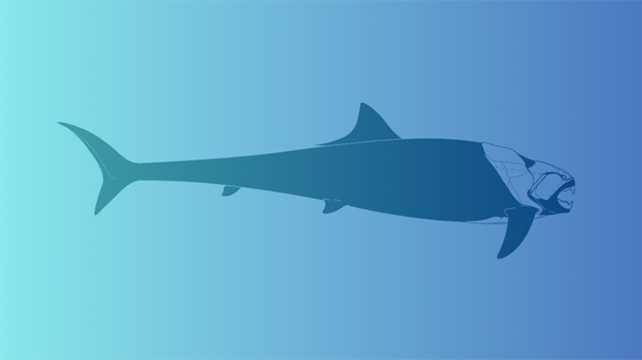

It's more likely that the Dunkleosteus species actually had shorter bodies compared to their gaping mouths, the new research suggests, with proportions between head size and body size that don't match what we see with the sharks of today.

"Dunkleosteus has often been assumed to function like a great white shark, but as we learn more about this fish, it might be more accurate to describe it as a mix of shark, grouper, viperfish, tuna, and piraiba," says Engelman.

Looking at smaller ancient fish that we do have fossils for, the biology of a fish the size of Dunkleosteus, and the differences we know about between modern-day and prehistoric species, previous estimates in terms of overall length may need to be halved, Engelman concludes.

In a second analysis putting his own newly devised method for estimating body size to the test, Engelman suggests that the largest Dunkleosteus only grew to about 4 meters, or 13 feet, in length.

Understanding just how big these underwater beasts were is crucial in understanding what life was like all those millions of years ago; a fish's size affects everything from its habitat to its evolution to the other fish it feeds on.

"Mouth size is probably the biggest factor in determining the largest prey a fish can eat," says Engelman, who estimates an adult Dunkleosteus could have possibly bitten off 22.9 kilograms of flesh in a single munch.

"The results of this study suggest arthrodires were hitting far above their weight class."

The research has been published in PeerJ Life & Envrionment.