The tiny cuts and grooves that decorate some ancient human artifacts are not just pretty accidents, according to some archaeologists. The subtle patterns could be early signs of creativity and symbolic thinking in our stone-knapping ancestors.

A new study led by researchers at the Hebrew School of Jerusalem in Israel has determined that several ancient human artifacts made in the Levant region between 50,000 and 100,000 years ago were designed with subtle yet "intentional engravings."

Today, the Levant region encompasses the land bridge between Africa and Eurasia – so naturally, it was one of our ancestors' first stops out of Africa all those millennia ago. It was there we began to improve our toolmaking, but there may be more to these tools than their function.

Under the microscope, researchers at the Hebrew School of Jerusalem found that some Levantine stone tools contain clear geometric designs. The lines are not merely hack marks, as other experts have argued in the past; they would have required intent, planning, and execution.

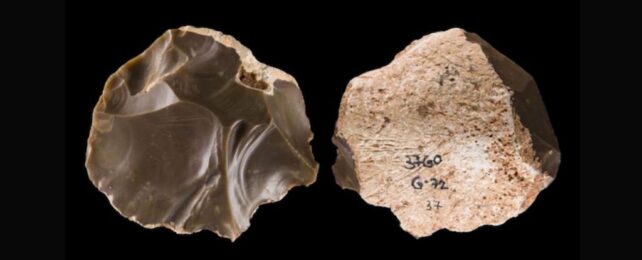

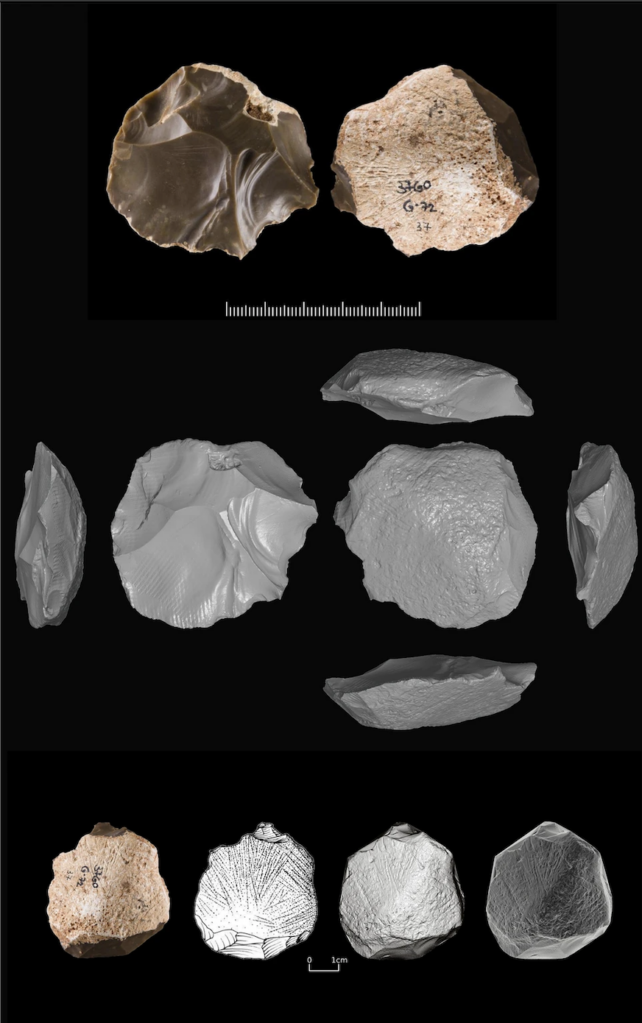

Two of the stone tools analyzed were made using the Levallois knapping technique of the Levant Stone Age, in which a flint stone core is essentially flaked away to make a point that can cut and hack. One tool dates to the Middle Paleolithic, while the other dates to 100,000 years ago.

Like ornamental seashells, ochre paint, or other engraved artifacts made of stone, bone, or ostrich egg shells, these engravings may indicate symbolic human behavior that is non-functional – an early bridge between beauty and utility.

In the past, some experts have interpreted the engravings on these very same Levantine tools as "proto-aesthetic", which means they were chiseled because they presented a pleasing visual pattern, not necessarily a symbolic one.

It's hard, if not impossible, to prove the intentions of people that lived tens of thousands of years ago, but the authors of the most recent analysis suspect there is more to the story than just a visually pleasing pattern.

"Abstract thinking is a cornerstone of human cognitive evolution," says archaeologist and lead author Mae Goder-Goldberger.

"The deliberate engravings found on these artifacts highlight the capacity for symbolic expression and suggest a society with advanced conceptual abilities."

The team's conclusions are based on a careful analysis of the stone flint cores in comparison to other ancient stone artifacts made in the Levant region.

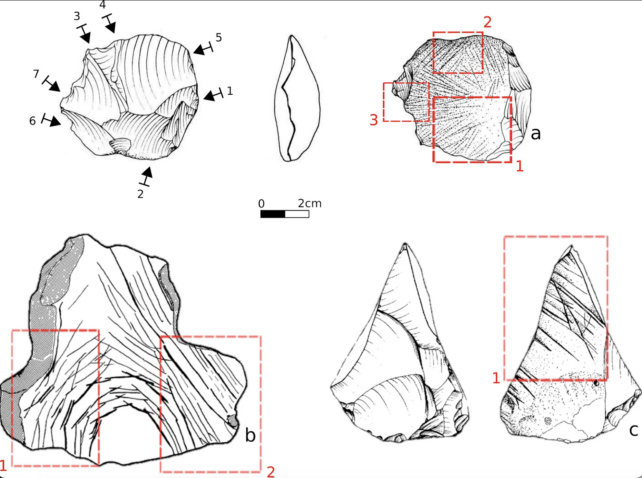

The two stone cores compared by Goder-Goldberger and her team are unusual from others found in the Levantine because they show engraved patterns on their surfaces, like a radiating fan of lines.

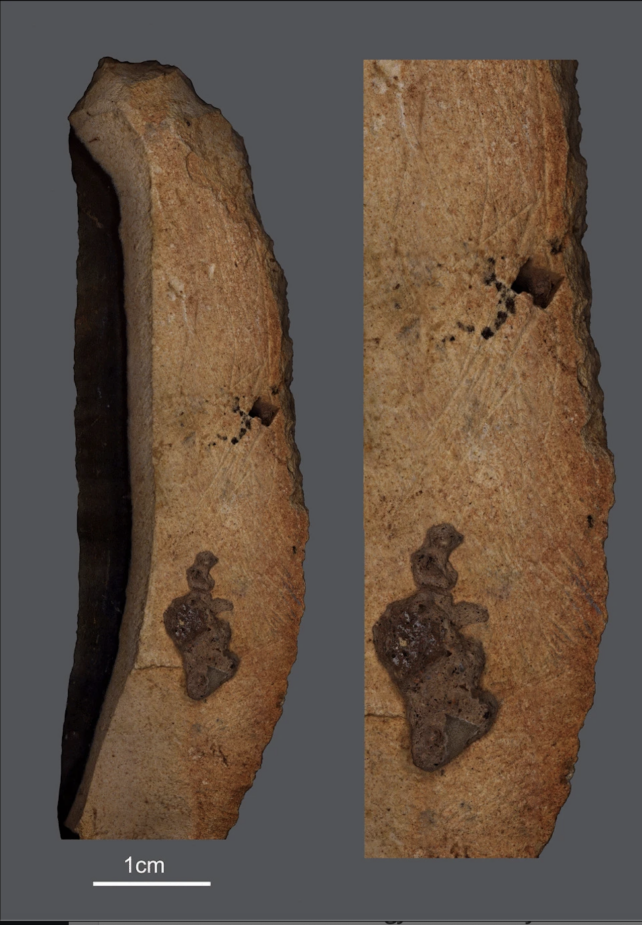

By contrast, the incisions made on a blade from Amud cave, constructed more than 55,000 years ago, are not perfectly spaced, nor do they create a clear pattern.

The geometric lines from the stone core tools are clustered in certain "areas of interest", and some are dissected by flake removals, which suggests they were engraved before the final stage of flaking, not after the tool was in use.

Another stone artifact, a plaquette from the Levantine, was analyzed because it was made without any known utility around 54,000 years ago. Its surface also hosts similar geometric patterns to the Levant cores.

Based on the similarities between the stone artifacts found at all three sites in the Levant, Goder-Goldberger and her colleagues think their decorations were produced by "sharp-edged non-retouched tools (likely stone tools) by applying a single stroke per incision". This technique, they say, is suggestive of "intent and creativity."

If the authors are right, something other than subsistence and sustainability may have been driving the construction of these stone tools and the intent of their knappers all those tens of thousands of years ago.

"The methodology we employed not only highlights the intentional nature of these engravings," says archaeologist João Marreiros from the Leibniz Centre for Archaeology in Germany, "but also provides for the first time a comparative framework for studying similar artifacts, enriching our understanding of Middle Paleolithic societies."

The study was published in Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences.