An exceptional amber deposit from roughly 40 million years ago has captured a rare form of parental care in plants – so rare it's only been reported once before on Earth.

Within the deep yellow depths of this beautiful fossil, you can still make out the seeds of an ancient pine cone. What makes it so unusual is that seeds are already germinating, sprouting with greenery before their cone has 'delivered birth'.

Usually, pine cones fall to the ground and then open up when the climate becomes warm and dry, releasing their seeds into the soil, where they then germinate on their own.

The germination of seeds and the growing of seedlings from within the parent plant is what scientists call 'precocious germination', or 'seed viviparity'. This animal-like upbringing is usually only observed in flowering plants, and even then, it occurs in less than 0.1 percent of species.

Among gymnosperms, like conifers, it seems all but nonexistent.

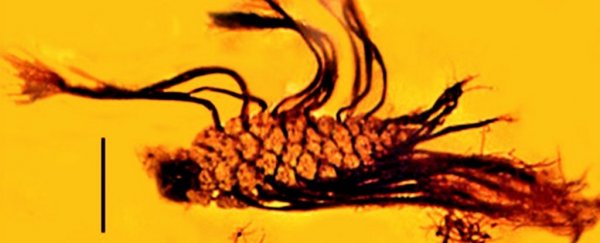

That's what makes this new amber deposit so special. The images below show several embryonic stems bursting through the female parent cone.

(Poinar, Historical Biology, 2021)

(Poinar, Historical Biology, 2021)

Above: The sprouting roots of embryos from within the parental cone. The scale bar measures 650 μm.

A closer look at the embryonic roots. The scale bar measures 400 μm. (Poinar, Historical Biology, 2021)

A closer look at the embryonic roots. The scale bar measures 400 μm. (Poinar, Historical Biology, 2021)

Scientists have only observed this phenomenon once before, in 1965. Within a single pine cone from a Himalayan pine (Pinus wallichiana), researchers identified the germination of seeds.

Researchers couldn't figure out why this had happened, although some scientists suspect frost or cold conditions may keep a pine cone from opening up and releasing its seeds, allowing them to stay warm and toasty inside instead.

"Seed germination in fruits is fairly common in plants that lack seed dormancy, like tomatoes, peppers, and grapefruit, and it happens for a variety of reasons," explains biologist George Poinar from Oregon State University.

"But it's rare in gymnosperms."

The amber deposit in this case comes from the Samland Peninsula of Russia, which juts out into the southeastern Baltic Sea.

The exact date is not clear, but the deposit was probably formed sometime during the late Eocene or early Cenozoic, between 30 to 60 million years ago.

Despite all that time, the fossilized pine cone is in remarkable condition. At the tips of each embryonic sprout, researchers can still see clumpings of tiny pine needles.

(Poinar, Historical Biology, 2021)

(Poinar, Historical Biology, 2021)

Above: Five needles from the pine cone in Baltic amber (one is broken). The scale bar measures 100 μm.

Because these needles are clustered together in groups of five, the authors think the ancient species is probably related to another extinct pine found in the same amber source, called Pinus cembrifolia.

Unlike these other examples, this particular pine cone sticks out. It is the only fossil record of precocious germination among plants, according to the authors.

(Poinar, Historical Biology, 2021)

(Poinar, Historical Biology, 2021)

Above: This is what ancient pine cones usually look like within amber. The scale bar measures 630 μm.

"That's part of what makes this discovery so intriguing, even beyond that it's the first fossil record of plant viviparity involving seed germination," says Poinar.

"I find it fascinating that the seeds in this small pine cone could start to germinate inside the cone and the sprouts could grow out so far before they perished in the resin."

Of course, that's only a possibility. It's not yet clear if the embryos bursting through the pine cone germinated before or after it ended up in the amber.

There are, however, cases of some movement still occurring even after an organism gets trapped in amber, like parasites trying to flee from their doomed hosts.

Under the microscope, the protruding roots within the pine seem to be covered in a thin cuticle, which the authors say could have kept the resin from infiltrating and killing the budding plant.

"This first fossil record of seed viviparity in plants shows that plant viviparity existed in gymnosperms during the Eocene," Poinar concludes in the study.

"This condition probably occurred much earlier in vascular plants and there is no reason why viviparity couldn't also have existed in spore-bearing plants like lycopods and ferns dating back to the Devonian."

Perhaps one day, we'll find some precocious embryos among those plants, too.

The study was published in Historical Biology.