A skull fragment found in Greece has inspired a startling hypothesis about when our species first arrived in Europe and immediately generated excitement and skepticism among experts who study how and when Homo sapiens dispersed from Africa.

Researchers say the fossilized skull, found in the late 1970s in a cave in southeast Greece and stored since then in a museum, belonged to an individual with anatomically modern features who lived about 210,000 years ago.

If true, that would be earliest example of Homo sapiens ever discovered outside the African continent. The date also precedes by a whopping 160,000 years the age of any Homo sapiens fossil previously found in Europe.

The bold claim, published Wednesday in the journal Nature, comes from a respected team of researchers, but it was met with caution from a number of other paleoanthropologists who were not involved in the research.

Disagreement is not unusual for this field, in which hypotheses and conjectures about human prehistory can emerge from a solitary jawbone or even a finger. Fossils are rare, difficult to date and usually fragmentary, and human prehistory is inherently a misty narrative.

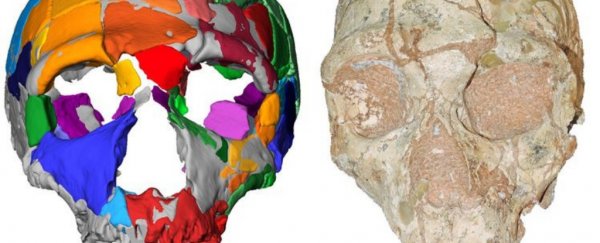

The new study focuses on the damaged remains of two skulls - named Apidima 1 and Apidima 2 - found just inches apart in a crevice. Initially scientists assumed the skulls were of the same age because they were found together.

But researchers recently used laboratory techniques that looked at the radioactive decay of trace amounts of uranium in the specimens, and concluded that the individuals came from different eras. The tests indicated that Apidima 1 is about 210,000 years old and Apidima 2 about 170,000 years old.

Those dates contained a shocking twist to the consensus about early humans in Europe. The researchers used a variety of methods to model what the skulls would have looked like before being shattered and distorted across thousands of centuries.

Apidima 2, the younger skull, looks clearly Neanderthal, which fits nicely with the understanding that Neanderthals - Homo neanderthalensis - were the dominant early humans in Europe in that period of prehistory.

But the older skull, Apidima 1, doesn't look like it belonged to a Neanderthal, the scientists found. It looks more like an early Homo sapiens, they report.

There's not much to this skull - just part of the back of the cranium. But it has a rounded shape and other features that the researchers liken to early modern humans.

Such an early presence of early modern humans in Europe is not implausible. Last year a different team of researchers reported the discovery in a cave in Israel of what they say is a Homo sapiens jawbone and teeth from an individual that lived roughly 177,000 to 194,000 years ago.

The new study proposes that the Levant and Turkey could have been migration routes for early modern humans to reach southeast Europe.

If this new interpretation is correct, the authors writer, Apidima 1 is "the earliest known presence of Homo sapiens in Eurasia, which indicates that early modern humans dispersed out of Africa starting much earlier, and reaching much further, than previously thought."

This discovery also suggests that the early modern humans had contact with Neanderthals, who went extinct about 40,000 years ago, after a group of modern humans (often referred to as Cro-Magnons) had arrived in western Eurasia in force.

An extraordinary claim like this comes with inherent challenges. It's essentially a single data point: one partial skull, damaged and distorted, with a "lack of archaeological context," in the words of the new paper.

There's nothing else: No stone tools, no burial signs, nothing to suggest modern human behavior. The claim would obviously benefit from a second Homo sapiens fossil of similar age somewhere in that part of the world.

"Of course it would be lovely to find more," said lead author Katerina Harvati of Eberhard Karls University of Tubingen, in Germany, in a conference call with reporters. "We intend to try to look."

Several paleontologists who read the paper came away skeptical. Rick Potts, director of the human origins program at Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History, said the new claim is a "one-off" with a date significantly different from what has been previously documented. That doesn't mean it's wrong, though.

"Of course there's got to be a time when you find the first one. But we don't know yet until we find multiple examples of this," he said.

Melanie Lee Chang, a Portland State University evolutionary biologist who specializes in human evolution, echoed that sentiment: "Right now it is an outlier. It could be that there are whole lot of specimens in cabinets that people haven't looked at in a while and will go back and reinterpret like this. But I'm not willing to sign on to all of their conclusions here."

John Hawks, a University of Wisconsin paleoanthropologist, said genetic evidence has shown that Neanderthals had genes from African ancestors sometime before 200,000 years ago, and thus "finding a skull that might be that age that has clearly what seems like African modern human features make a lot of sense."

But he also sounded a cautionary note. It's odd, he said, that two skulls of such different ages were found right next to one another. The researchers believed the fossils were washed into a crevice and then were embedded in sediments that hardened about 150,000 years ago.

Said Hawks, "This is a weird scenario to have two human skulls that are next to each other that are so different in age, and it makes me want more evidence."

One co-author of the Nature paper, Chris Stringer of the Natural History Museum of London, acknowledged that this is a "challenging new find" for which skepticism is appropriate initially.

"We don't have the frontal bone, browridge, face, teeth or chin region, any of which could have been less 'modern' in form," he said in an email. But he said the team tested their reconstruction efforts in multiple ways and that the fossil "certainly shows the high and rounded back to the skull that is typical only of H. sapiens."

He said it would be helpful to find stone tools associated with Homo sapiens. "If we have interpreted the Apidima evidence correctly, the handiwork of these early H. sapiens must be present elsewhere in the European record," he said.

All people alive today appear to have descended from an ancestral group in Africa that lived roughly 70,000 years ago. "Both the fossil evidence and genomic evidence of modern day humans still suggest that the permanent success of Homo sapiens beyond the African continent is maybe 70,000 years old," Potts said.

But the finer details of human prehistory, including the fate of groups that dispersed but apparently died out, have gotten more complicated with each new discovery.

There was not a single, linear evolution of humans - which was the presumption among paleoanthropologists just half a century ago - but rather many hominid species that coexisted for millions of years before a single species replaced everyone else.

"We're the last biped standing of what used to be a very, very diverse evolutionary tree," Potts said.

2019 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.