A smattering of ancient rock walls along the river Nile in Sudan appear to represent the oldest known hydraulics system of their kind.

New findings suggest people living in the ancient empire of Nubia in northern Sudan were manipulating the river to their advantage as far back as 3,000 years ago.

River 'groynes' are rigid structures, laid perpendicular to a shore or bank, that humans still use to this day to manipulate the flow of water and silt.

They're highly useful, and farmers and boaters along the Nile have known that for much longer than we ever knew.

The Yellow River in China used to have the oldest known groynes in the world. But not anymore.

Researchers in Australia and the United Kingdom have found evidence that Nubians were using groynes 2,500 years before farmers in China were doing the same.

Using satellite data, local surveys, and previous studies, the team revealed hundreds of groynes that still stand in Sudan to this day.

Some are buried under the waters of the Nile, while others stand on ancient riverbeds that have long since dried out.

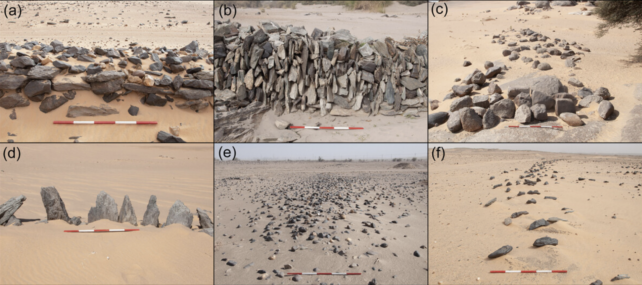

Their shape, orientation, and size say a lot about their possible purposes.

Researchers suspect they were used to trap fertile silt, to irrigate land, to limit bank erosion, to defend against seasonal floods, to create optimal fishing pools, or to stop winds of sand from smothering crops.

The system is so effective, it's actually still employed by locals, although not in the same spots. Climate changes over the past three millennia have significantly altered the flow of the Nile in this region.

"From speaking with farmers in Sudanese Nubia, we also learned that river groynes continued to be built as recently as the 1970s, and that the land formed by some walls is still cultivated today," says archaeologist Matthew Dalton from the University of Western Australia.

"This incredibly long-lived hydraulic technology played a crucial role in enabling communities to grow food and thrive in the challenging landscapes of Nubia for over 3,000 years."

Ancient humans living along the river Nile are known to have built canals and harbors for thousands of years, but groynes have never been independently dated, Dalton and his colleagues think.

The practice of installing river groynes along the Nile was assumed to be modern, dating to around the early 19th century, and yet other older-looking groynes also exist in the region.

Unfortunately, the groynes found near archaeological sites from Nubia are often submerged in active channels, which means they cannot be properly dated.

Still, the ones that exist on dry riverbed, near an ancient walled town known as Amara West, have now been dated to between 3,000 and 3,300 years old.

"All of the walls are situated in areas probably subjected to past inundations, with most also visibly abutted by silty flood units," researchers write.

The ones that create thick bedrock were probably used to halt water or trap fertile silt from the Nile, reducing the need for irrigation. Whereas those that are upright in a line might have been employed to block the sandy wind or coax fish into a calm pool.

Researchers suspect the structures were built to sustain large communities in a region where the flow of the Nile was not as strong or consistent as further north in Egypt.

Groynes would have made settlement in the region possible, especially if the flow of the Nile was waning, as climate records indicate.

Still, this Nubia oasis did not last forever. Around 1000 BCE, researchers say the region's drying climate became too inhospitable.

Around 200 BCE, the river's flooding in some regions probably stopped for good, and the groynes fell into disrepair.

Others were submerged.

Near the ancient temple of Soleb on the west bank of the Nile, for instance, researchers identified walls that stretch up to 700 meters (2,997 ft) long, made from boulders weighing 100 kilograms (220 pounds) a piece.

Unlike the river groynes found on dry land, these walls extend straight or hooked into active channels of the river, creating a deep, calm channel that likely improved boat access, like a modern pier or jetty.

Further research is needed to date these structures properly, but given the 3,000-year-old groynes found nearby, there's a chance these ones are equally as old.

"These monumental river groynes helped to connect the people of ancient Egypt and Nubia by facilitating the long-distance movement of resources, armies, people, and ideas up and down the Nile," marvels Dalton.

It's astonishing that their importance has largely escaped our notice until recently.

The study was published in Geoarchaeology.