Through a detailed analysis of the Kikai Caldera near Kyūshū island in Japan, scientists think they've confirmed the biggest eruption ever discovered to take place in the Holocene – an epoch that began around 11,700 years ago and continues today.

While the volcano has erupted more than once throughout its active history, accurately assessing the size of each blast has been tricky.

To determine the size of an event that occurred around 7,300 years ago known as the Kikai-Akahoya (K-Ah) eruption, a team of researchers from Kobe University in Japan combined sediment samples from the seabed with seismic imaging to map out the shape of the caldera and the materials in it, looking for evidence of volcanic ejecta.

"Large volcanic eruptions such as those yet to be experienced by modern civilization rely on sedimentary records, but it has been difficult to estimate eruptive volumes with high precision because many of the volcanic ejecta deposited on land have been lost due to erosion," says Kobe University geophysicist Nobukazu Seama.

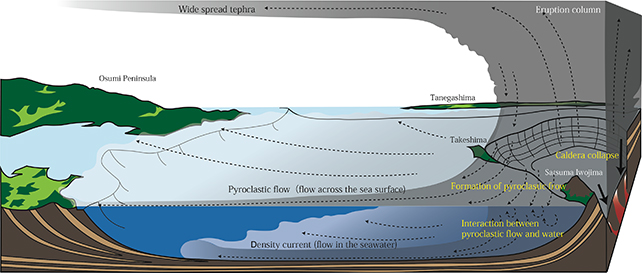

The team focused on what's called the pyroclastic flow of the K-Ah eruption; the intensely hot funnels of ash, rock, and gas that would've powered through the water all those millennia ago.

As you might imagine, this flow is hard to model underwater, especially so far into the past. However, water does do a good job of preserving this ejecta. The instruments used by the researchers were able to look deep below the seafloor, comparing different types of material in terms of where they originated and where they ended up.

The team found the material ejected by the eruption would've covered around 4,500 square kilometers (1,737 square miles), an area several times bigger than large metropolitan cities like London or Los Angeles.

Sending hundreds of cubic kilometers of rock and dust scattering, it is by some distance the largest volcanic eruption of the Holocene ever measured. Even the 1883 eruption of Krakatoa, which was heard around the world, blasted a mere couple dozen square kilometers of material into the stratosphere.

"By using seismic reflection surveys optimized for this target and by identifying the collected sediments, we were able to obtain important information on the distribution, volume, and transport mechanisms of the ejecta," says Satoshi Shimizu, a marine geophysicist at Kobe University.

The research should give experts a better idea of how volcanic eruptions pass through water in the future – all of which helps in volcano modeling. The more we understand past eruptions, the more accurately we can predict future ones.

Although we've seen some major eruptions in living memory, they're nothing like the super eruptions of the past – and considering the damage that one of them could do, it's something we need to be ready for.

"Giant caldera eruptions are an important phenomenon in geoscience, and because we also know that they influenced the global climate and thus human history in the past, understanding this phenomenon has also social significance," says Seama.

The research has been published in the Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research.