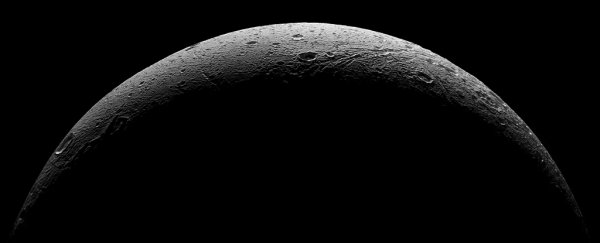

Scientists have uncovered evidence that there's a vast ocean hiding beneath the surface of Dione – Saturn's fourth largest moon.

If the find can be confirmed, Dione could join Saturn's other moons – Enceladus, Titan, and Mimas – all of which scientists think might have underground oceans that could host life.

Researchers from the the Royal Observatory of Belgium used a geophysical model to interpret new gravity readings taken by the NASA probe Cassini in 2015, and suggest the data can be explained by a 100-kilometre-thick (62-mile) shell of ice on top of a 62-kilometre-deep (39-mile) ocean.

That ocean - which would have been around since the moon was first formed - could lie on top of a rocky core, and astronomers are intrigued by what that might mean for the prospects of life on Dione.

"The contact between the ocean and the rocky core is crucial," says researcher Attilio Rivoldini. "Rock-water interactions provide key nutrients and a source of energy, both being essential ingredients for life."

The finding amounts to the latest evidence that water - and therefore, potentially, habitability - could be more common than we thought across the Solar System. Three more of Saturn's moons – Titan, Enceladus, and Mimas – are already suspected to have oceans hidden beneath their icy crusts.

The Belgian team used the same detective methods to build up their model of Dione as the Cassini researchers who made the Enceladus discovery based on flybys between 2010 and 2012.

During this mission, variations in the velocity of Cassini as it made flybys of Enceladus led scientists to conclude that the moon featured an underground ocean.

Why? Because such an ocean would cause changes in gravitational pull, and that could explain the ripples Cassini was detecting.

"For Dione, we did a similar gravity-topography analysis as was done for Enceladus in 2014, but with improved techniques," lead researcher Mikael Beuthe told Maddie Stone at Gizmodo. "[T]hat's the best evidence we have now for a present-day ocean on Dione."

There are no icy geysers spewing out of Dione, as there are on Enceladus, which would make it easier to determine if the underground ocean hypothesis was correct.

But gravity data suggest that radioactive elements inside Dione's core could be producing heat and melting the overlying ice, likely creating a subsurface ocean above the core.

And the researchers think that the contrasting cliffs and smooth terrain that make up Dione's surface are evidence of geologic activity below, which points to the existence of the hidden ocean.

If Dione were just ice and rock - with no watery ocean in between - we would expect to see more evidence of freezing and expansion in the form of cracks on its surface, the researchers say, but no such cracks can be seen.

Unfortunately, it's going to take years - and another spacecraft mission - before we can confirm if there really is water on this moon.

So we can't update our list of ocean worlds inside the Solar System just yet, but there are already thought to be three such worlds orbiting Jupiter, and three orbiting Saturn (not including Dione).

Neptune's moon Triton and Pluto are in the "possible" pile - and until we get another chance to study Dione up close, that's where this moon will stay too.

The findings are published in Geophysical Research Letters.