Antarctic glaciers have been melting at an accelerating pace over the past four decades thanks to an influx of warm ocean water - a startling new finding that researchers say could mean sea levels are poised to rise more quickly than predicted in coming decades.

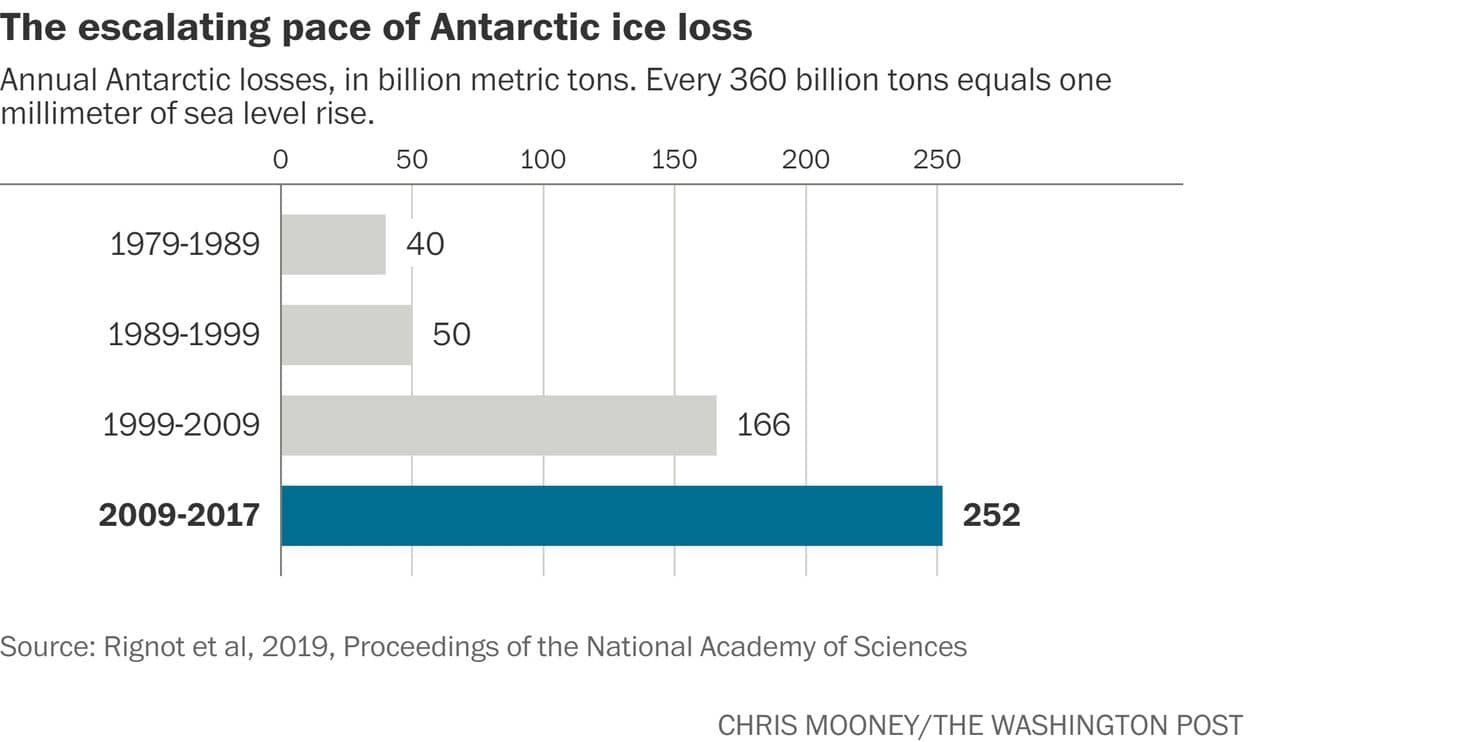

The Antarctic lost 40 billion tons of melting ice to the ocean each year from 1979 to 1989. That figure rose to 252 billion tons lost per year beginning in 2009, according to a study published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

That means the region is losing six times as much ice as it was four decades ago, an unprecedented pace in the era of modern measurements. (It takes about 360 billion tons of ice to produce one millimeter of global sea-level rise.)

"I don't want to be alarmist," said Eric Rignot, an Earth-systems scientist for the University of California at Irvine and NASA who led the work. But he said the weaknesses that researchers have detected in East Antarctica - home to the largest ice sheet on the planet - deserve deeper study.

"The places undergoing changes in Antarctica are not limited to just a couple places," Rignot said.

"They seem to be more extensive than what we thought. That, to me, seems to be reason for concern."

The findings are the latest sign that the world could face catastrophic consequences if climate change continues unabated. In addition to more-frequent droughts, heat waves, severe storms and other extreme weather that could come with a continually warming Earth, scientists already have predicted that seas could rise nearly three feet globally by 2100 if the world does not sharply decrease its carbon output.

But in recent years, there has been growing concern that the Antarctic could push that even higher.

That kind of sea-level rise would result in the inundation of island communities around the globe, devastating wildlife habitats and threatening drinking-water supplies. Global sea levels have already risen seven to eight inches since 1900.

The ice of Antarctica contains 57.2 meters, or 187.66 feet, of potential sea-level rise. This massive body of ice flows out into the ocean through a complex array of partially submerged glaciers and thick floating expanses of ice called ice shelves.

The glaciers themselves, as well as the ice shelves, can be as large as American states or entire countries.

The outward ice flow is normal and natural, and it is typically offset by some 2 trillion tons of snowfall atop Antarctica each year, a process that on its own would leave Earth's sea level relatively unchanged. However, if the ice flow speeds up, the ice sheet's losses can outpace snowfall volume. When that happens, seas rise.

That's what the new research says is happening. Scientists came to that conclusion after systematically computing gains and losses across 65 sectors of Antarctica where large glaciers - or glaciers flowing into an ice shelf - reach the sea.

West Antarctica is the continent's major ice loser. Monday's research affirms that finding, detailing how a single glacier, Pine Island, has lost more than a trillion tons of ice since 1979. Thwaites Glacier, the biggest and potentially most vulnerable in the region, has lost 634 billion.

The entire West Antarctic ice sheet is capable of driving a sea-level rise of 5.28 meters, or 17.32 feet, and is now losing 159 billion tons (144 billion tonnes) every year.

The most striking finding in Monday's study is the assertion that East Antarctica, which contains by far the continent's most ice - a vast sheet capable of nearly 170 feet (52 metres) of potential sea-level rise - is also experiencing serious melting.

The new research highlights how some massive glaciers, ones that to this point have been studied relatively little, are losing significant amounts of ice. That includes Cook and Ninnis, which are the gateway to the massive Wilkes Subglacial Basin, and other glaciers known as Dibble, Frost, Holmes and Denman.

Denman, for instance, contains nearly five feet of potential sea-level rise alone and has lost almost 200 billion tons of ice, the study finds. And it remains alarmingly vulnerable.

The study notes that the glacier is "grounded on a ridge with a steep retrograde slope immediately upstream," meaning additional losses could cause the glacier to rapidly retreat.

"It has been known for some time that the West Antarctic and Antarctic Peninsula have been losing mass, but discovering that significant mass loss is also occurring in the East Antarctic is really important because there's such a large volume of sea-level equivalent contained in those basins," said Christine Dow, a glacier expert at the University of Waterloo in Canada.

"It shows that we can't ignore the East Antarctic and need to focus in on the areas that are losing mass most quickly, particularly those with reverse bed slopes that could result in rapid ice disintegration and sea-level rise."

The new research is consistent in some ways with a major study published last year by a team of 80 scientists finding that Antarctic ice losses have tripled in a decade and now total 219 billion tons annually. That research did not find similarly large losses from East Antarctica, though it noted that there is a high amount of uncertainty about what is happening there.

"More work is needed to reconcile these new estimates," said Beata Csatho, an Antarctic expert at the University at Buffalo who was an author of the prior study.

The bottom line is that Antarctica is losing a lot of ice and that vulnerable areas exist across the East and West Antarctic, with few signs of slowing as oceans grow warmer. In particular, Rignot says, key parts of East Antarctica, the subject of less focus from researchers in the past, need a much closer look, and fast.

"The traditional view from many decades ago is that nothing much is happening in East Antarctica," Rignot said, adding, "It's a little bit like wishful thinking."

2019 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.