It was an unprecedented blip out of nowhere in 1982. For the first time, scientists confirmed the first earthquake in Antarctica – but it wouldn't be the last.

As the decades passed, researchers detected eight more seismic events in East Antarctica. And then all hell seemingly broke loose, with sensors picking up 27 earthquakes in 2009 alone, tripling the total number of recorded events ever in just a single year.

But it wasn't a planetary catastrophe or divine wrath that lay behind the ground shaking like nothing known before – merely the scientific method in action.

"Ultimately, the lack of recorded seismicity wasn't due to a lack of events but a lack of instruments close enough to record the events," explains seismologist Amanda Lough from Drexel University.

While Antarctica's unusual silence in terms of seismic activity had been the subject of numerous scientific hypotheses, Lough showed it wasn't a quirk of tectonics keeping the endless white landscape still – just a lack of data.

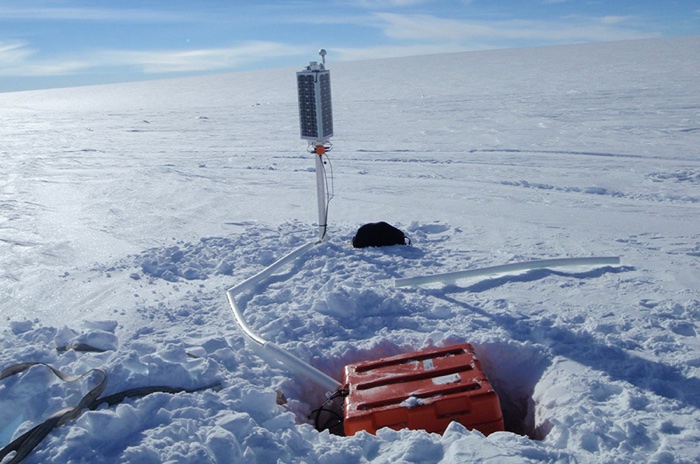

One of the seismic sensors (Drexel University)

One of the seismic sensors (Drexel University)

In 2007 she began the epic multi-year task of installing the GAMSEIS/AGAP array of broadband seismographs in East Antarctica, giving scientists an unprecedented glimpse at the region's seismic activity.

Like the 2009 data demonstrate, Antarctica experiences its share of earthquakes and seismic movement just like other parts of the globe, only now we have the recorded observations to prove it.

"It's no longer an anomaly," she told Quartz, noting that the 2009 results took even the research team back, leading to "quite a bit of checking to make sure that they were real events and that we had located them accurately."

In the team's new study on the earthquakes detected, the researchers explain that East Antarctica is a craton – a large, stable piece of rock on the Earth's crust underlying continents.

While some had reasoned seismic activity in Antarctica might be suppressed by the immense weight of the continental ice sheet, the new findings show that's not the case.

Most of the 27 earthquakes in 2009 were the result of rifts – regions in the crust where the rock is being torn apart.

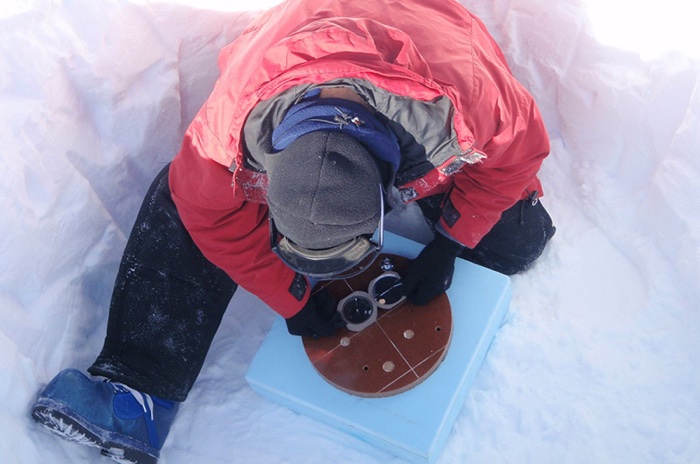

Calibrating one of the sensors (Drexel University)

Calibrating one of the sensors (Drexel University)

"The rifts provide zones of weakness that enable faulting to occur more easily, and it may be that the situation here is such that activity is occurring preferentially along these areas of pre-existing weakness," Lough explains in a press release, although she notes the present findings are based on only one year of data, so more research needs to be done to get the full picture.

But it just goes to show how blind scientists – and by extension, all of us – really are without the right tools to record and detect physical phenomena.

And while the East Antarctica blindspot seems amazing in hindsight, the truth is there's still a lot we're not recording sufficiently in terms of global seismic activity.

"Antarctica is the least-instrumented continent, but other areas of the globe also lack sufficient instrumentation," Lough says.

"The ocean covers 71 percent of the planet, but it is expensive and very difficult to get instruments there. We need to think about improving coverage and then improving the density of it."

The findings are reported in Nature Geoscience.