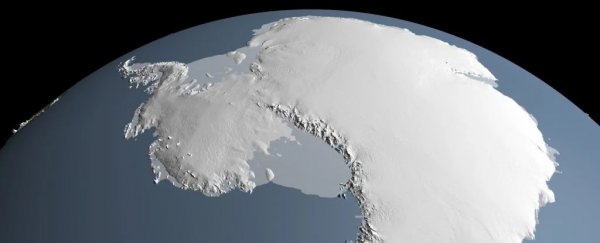

Scientists call it the doomsday glacier.

That's partly because the Thwaites, a Britain-sized glacier in western Antarctica, is melting at an alarming rate: It's retreating by about half a mile (2,625 feet) per year. Scientists estimate the glacier will lose all of its ice in about 200 to 600 years. When it does, it will raise sea levels by about 1.6-2 feet (0.5 metres).

But the sea-level rise wouldn't stop there. Thwaites' nickname stems mostly from what would happen after it melts.

Right now, the glacier acts as a buffer between the warming sea and other glaciers. Its collapse could bring neighbouring ice masses in western Antarctica down with it. Added up, that process would raise sea levels by nearly 10 feet, permanently submerging many coastal areas including parts of New York City, Miami, and the Netherlands.

"It's a major change, a rewriting of the coastline," David Holland, a professor of atmospheric science at New York University who contributes research to the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration, told PBS NewsHour in February.

This moth, two new studies have added detail to the alarming picture. Research published last week in the journal Cryosphere found that warm ocean currents may be eating away at the Thwaites Glacier's underbelly.

A study published Monday, meanwhile, used satellite imagery to show that sections of Thwaites and its neighbour, the Pine Island Glacier, are breaking apart more quickly than previously thought. That work was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The images below reveal what's happening to the Thwaites and nearby glaciers, along with what could happen in the future.

The melting of the Thwaites and Pine Island Glaciers already account for about 5 percent of global sea-level rise.

(Lhermitte et al., PNAS, 2020)

(Lhermitte et al., PNAS, 2020)

Above: Satellite imagery between October 2014 and May 2019 shows extensive damage to the Thwaites and Pine Island Glaciers.

It's not just the Thwaites: The Antarctic ice sheet is melting six times faster than it was in the 1980s. It's shedding 252 billion tons annually, up from 40 billion tons per year 40 years ago.

If the entire Antarctic ice sheet melted, scientists estimate sea levels would rise by 200 feet (60 metres).

Before-and-after images taken from space show the Thwaites glacier dissolving into the sea.

"What the satellites are showing us is a glacier coming apart at the seams," Ted Scambos, a senior scientist at the University of Colorado, told NASA in February.

This rapid melting is happening in part because natural buffers holding the Thwaites and Pine Glaciers in place are breaking apart, according to new research.

(Ian Joughin/University of Washington)

(Ian Joughin/University of Washington)

Above: Crevasses near the grounding line of Pine Island Glacier, Antarctica.

Crevasses like those in the image of Pine Island Glacier above form near glaciers' shear margins: areas where fast-moving glacier ice meets slower-moving ice or rock, which keeps it contained.

The new PNAS study found that shear margins on the Pine Island and Thwaites Glaciers are weakening and breaking apart, which could cause ice to flow into the ocean.

The looming loss of the Thwaites Glacier is so worrisome that the US and UK created an international agency to study it.

That organisation, the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration, studies the glacier via icebreaker ships that can break through thick ice sheets.

In February, researchers discovered a cavity nearly the size of Manhattan on the underside of Thwaites.

(NASA/OIB/Jeremy Harbeck)

(NASA/OIB/Jeremy Harbeck)

Above: A cavity nearly 1,000 feet tall is growing at the bottom of Thwaites Glacier in West Antarctica.

The cavity, which NASA scientists found using ice-penetrating radar in 2019, could have held 14 billion tons of ice.

The diagram below shows how warm underwater currents move beneath the glacier, slowly melting it from the bottom up.

(International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration)

(International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration)

Above: A 3D diagram of the Thwaites glacier, illustrating sea-floor channels that may carry warm water to the glacier's underside and cause melting.

When ice sheets melt from below, they can lose their structure, causing them to melt even faster and disintegrate into the ocean, as Thwaites is doing.

Researchers calculated that the Pine Island Glacier has lost an area the size of Los Angeles in the last six years.

"These are the first signs we see that Pine Island ice shelf is disappearing," Stef Lhermitte, a satellite expert and lead author on the PNAS study, told the Washington Post.

"This damage is difficult to heal."

Sea level rise could affect as many as 800 million people by 2050, according to a 2018 report.

(Climate Central)

(Climate Central)

Above: A projection of what New York City's sea levels would look like with 10 feet of sea-level rise.

The report, from the C40 Cities climate network, found that sea-level rise could threaten the power supply to 470 million people and regularly expose 1.6 billion people to extreme high temperatures.

This article was originally published by Business Insider.

More from Business Insider: