Antibiotic resistant bacteria is one of the biggest issues we facing in the coming decades, but there's one type of spread that isn't getting enough attention, says a new study – antibiotic resistance genes are spreading through the air.

If that sounds terrifying to you, you're not alone.

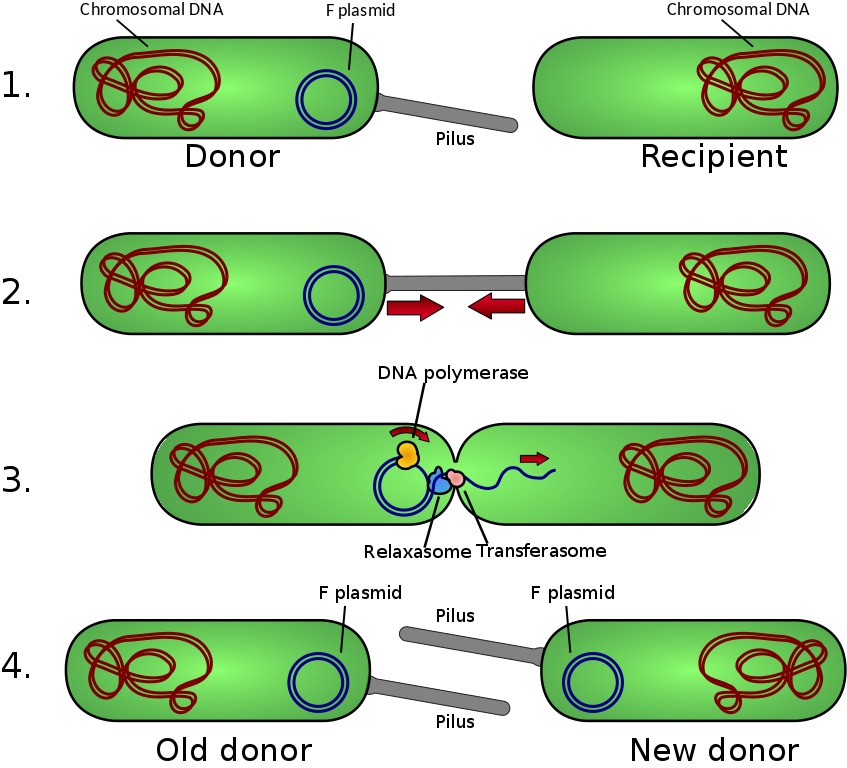

Bacteria's antibiotic resistance genes aren't just inherited through reproduction – in the case of bacteria that's asexual reproduction, where one parent cell becomes two daughter cells, also known as vertical gene transfer.

Unlike humans, bacteria can also spread their genes through something called horizontal gene transfer, where bacteria will replicate and then gift genes to other bacteria through a needle-like mechanism called a pilus.

But bacteria don't even need to be alive to pass their genes on horizontally, because once they die they release their entire insides into their environment – leaving little DNA packages around for other bacteria that happen to pass by.

The act of bacteria literally reaching out, picking up DNA from its environment and hauling it back into itself with its pilus, was recently captured on camera for the first time.

To make matters worse, both dead and alive bacteria can easily become airborne, moving to new locations and spreading their genes further abroad.

(Adenosine/Wikimedia/CC BY 3.0)

(Adenosine/Wikimedia/CC BY 3.0)

An international collaboration led by researchers from Peking University in Beijing, wanted to take a survey of just how prevalent and varied these airborne genes are.

The bad news: they're everywhere.

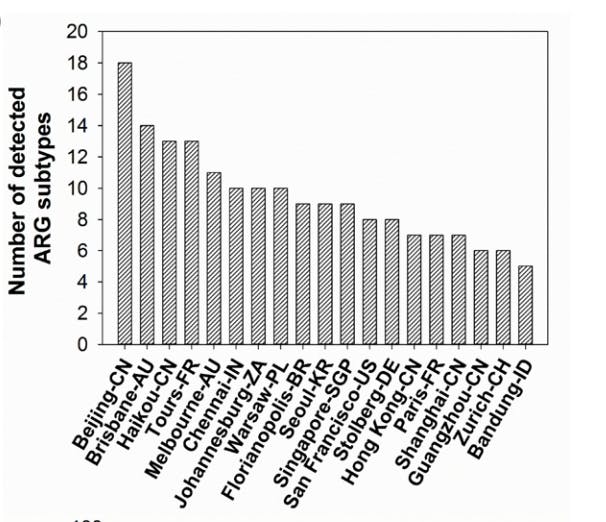

Between 2016 and 2017, the team surveyed 30 different types of airborne antibiotic resistance genes across 19 cities around the world, including San Francisco, Paris and Melbourne.

They found that Beijing, China and Brisbane, Australia had the most different types of airborne antibiotic resistance genes, but San Francisco had the highest level overall.

Cities showing diversity of antibiotic resistance genes in the air. (Environmental Science and Technology)

Cities showing diversity of antibiotic resistance genes in the air. (Environmental Science and Technology)

The researchers believe that inhaling the airborne antibiotic resistance genes could lead to the spread of this resistance in our lungs and end up affecting our immune system.

"Due to aerial transport, remote regions even without using antibiotics could be exposed to the 'second hand' antibiotic resistance genes, which are initially being developed in other regions but transported elsewhere," the team wrote.

Even more worrying, low levels of genes resistant to vancomycin, an antibiotic of last resort for MRSA treatment, were found in the air of six cities.

So how do areas with relatively low air pollution end up with so many bacterial genes in the air? The researchers think it has to do with wastewater treatment plants, hospitals or animal feeding operations.

Wastewater, specifically, can be treated with antibiotics that, can lead the survivors to pass on their antibiotic resistance genes. Wastewater is also likely to become aerosolised, which could be a problem if it then spreads to neighbouring areas.

The team stresses that this isn't the only or most important thing to look at when investigating antibiotic resistance in populations, but it has been something that's been typically overlooked, which this research shows might need to change.

"Among the detected cells in urban air, those airborne viable bacteria carrying different antibiotic resistance genes can certainly cause more harm than genes itself and those gene-carrying dead cells," the researchers added.

"However, the long-term microecological consequences for both atmosphere and human respiratory system resulting from exposure of airborne antibiotic resistance genes remain to be further explored."

The research has been published in Environmental Science and Technology.