The mcr-1 gene, which helps bacteria resist colistin – one of the few remaining antibiotic drugs of last resort that still work – has now reached hospitals all across the world.

And thanks to new research, we now have more evidence of where it came from – pig farms in China.

While experts had previously thought the gene developed on Chinese pig farms, due to their extensive use of colistin on the animals, the latest study offers more evidence to back this idea up.

It pinpoints the start of the spread to sometime in 2005.

Although there's nothing good about the rise of mcr-1 and antibiotic resistance in general, the genetic analysis techniques used in this research could help scientists get a better handle on the spread of superbugs in the future.

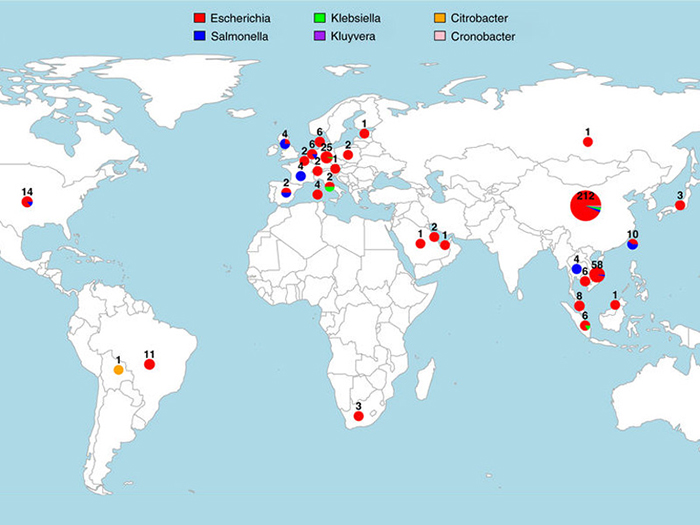

Tracking mcr-1 around the world. (UCL)

Tracking mcr-1 around the world. (UCL)

"The speed at which mcr-1 spread globally is indeed shocking," says lead researcher Francois Balloux, from University College London (UCL) in the UK.

By sequencing the genomes of 110 bacterial strains and comparing them to existing genomic data, the team identified a large dataset of 457 mcr-1 positive genome sequences, taken from humans and farm animals spread across five continents.

That enabled them to show exactly where mcr-1 had emerged from, and how it spread globally – attaching itself to various bacterial pathogens by "hitchhiking" on different mobile genetic elements.

"By deciphering the genetic code of these bacteria we found it was possible to predict not only how and where but also when mcr-1 started to spread," says one of the researchers, Lucy van Dorp from UCL.

"This is so important as the presence of mcr-1 across the globe, in many different bacteria species, all within only a decade highlights the ease and speed with which these resistant genes can be disseminated."

Now we've been able to track how mcr-1 spreads, we might be able to better prepare ourselves for the next antimicrobial resistance gene (AMG) to emerge. That's going to take a worldwide effort and a lot of cooperation between countries, the researchers say.

Because of its potentially severe side effects, colistin is only used as an antibiotic of last resort for infections such as E. coli, but the spread of mcr-1 is rendering it ineffective.

The gene can hop between bacteria of different species, making it very difficult to stop.

As hospitals continue to struggle against the rise of the superbugs, and experts warn that the situation is gradually going to get worse, scientists are scrambling for ways to upgrade our medications to meet the challenge. DNA sequencing could be one way to do that.

"Given the dearth of new antibiotics in the pipeline, our best hope to avert the current public health crisis is to improve stewardship of existing drugs, by harnessing the potential of bacterial genome sequencing and translate it into improved surveillance and diagnostics tools," says Balloux.

The findings have been published in Nature Communications.