An antibody is a class of protein called an immunoglobulin, which is made by specialised white blood cells to identify and neutralise material foreign to an immune system.

Shaped like a 'Y', antibodies contain a highly-variable region in their fork, which allows the immune system to tailor its response to a countless range of threats.

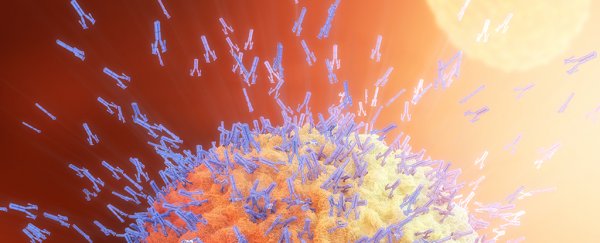

This unique make-up of different antibodies allows them to bind specifically to complex chemical signatures, known as antigens, which are found on the outer layers of invasive pathogens, like viruses and bacteria, as well as cancerous cells.

By binding with these surface markers, antibodies can interfere with the cell's or microbe's functions, rendering them immobile or unable to carry out tasks necessary for replication.

Their binding can also trigger two kinds of immune responses.

One involves a domino-effect of changes among what's known as a complement system of signalling molecules in the body. This cascade of chemical reactions can have a range of effects on the body, prompting a variety of immune responses, such as inflammation as well as physically disrupting and destroying the pathogen.

A second response, referred to as opsonisation, recruits specialised white blood cells called phagocytes to ingest and maybe even digest the targeted material.

How are antibodies made to be so specific?

Antibodies are produced inside white blood cells known simply as B-cells. These cells start life inside bone marrow, before maturing as they circulate through the body's blood vessels.

Part of their development involves assembling key segments of immunoglobulin genes to churn out antibodies with random structures. Thanks to the mix-and-match genetics of antibody production, humans can generate up to one quintillion unique antibodies.

B-cells that produce antibodies which happen to match material found inside their own body are destroyed before they make it into the blood stream. Exceptions give rise to a class of disorders known as an autoimmune disease.

Antibodies from mature B-cells that successfully bind to foreign antigens are encouraged to reproduce, swelling their numbers to provide a multitude of antibody 'factories' that can deal with a potential infection.

Some B-cells can be preserved in the body for years, creating a catalogue of past infections that can be deployed quickly in the event of future infections.

How are antibodies used in medicine?

Antibodies can be used directly and indirectly as a treatment for disease, a preventative form of medicine, and in diagnostics.

Vaccines provokes B-cells into making and preserving a supply of antibodies by introducing antigens, in expectation of future infections.

Alternatively, specific (or monoclonal) antibodies can be generated outside the body for use in therapies against existing infections or illnesses, targeting cancer cells or even animal venom.

Monoclonal antibodies can also be applied to laboratory samples to detect the presence of antigens in test substances. A common pathology test called an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), for example, uses coloured dyes to indicate the presence of antigens sticking to antibodies anchored to diagnostic kits.

All topic-based articles are determined by fact checkers to be correct and relevant at the time of publishing. Text and images may be altered, removed, or added to as an editorial decision to keep information current.