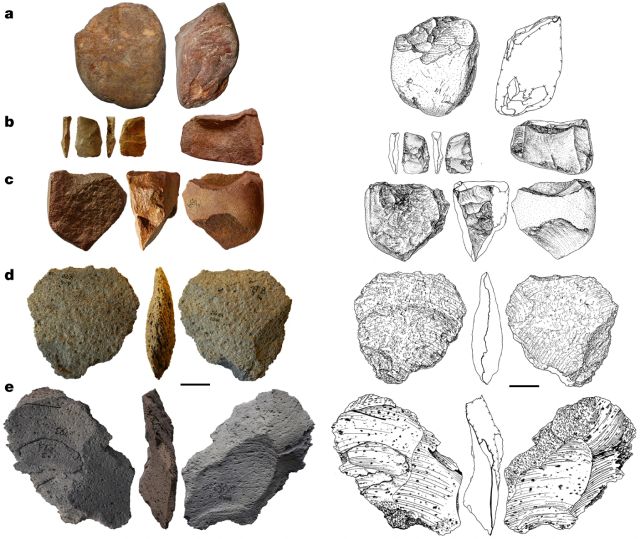

Stone tools found buried deep in the sediment of the Korolevo quarry in Ukraine are rewriting the history of human migration.

The seemingly unassuming chunks of rock are tools once used by Homo erectus, a direct ancestor of ours, and new dating reveals they represent the earliest evidence of hominid habitation on the European continent.

"Previously it was thought that our earliest ancestors could not survive in colder, more northerly latitudes without the use of fire or complex stone tool technology," says archaeologist Andy Herries of La Trobe University in Australia.

"Yet here we have evidence of Homo erectus living further north than ever previously documented at this early time period."

The history of humanity's evolution and dispersal throughout the world is a difficult puzzle to piece together. However, in recent years, evidence has started to emerge that it wasn't a simple, linear narrative originating in a single cradle in one part of the world. And several recent lines of evidence suggest that Homo sapiens may have been moving across Europe much earlier than we had previously thought.

Which is all to say that human history is looking a lot more complicated than we had previously credited, and our understanding thereof has some serious holes.

Our models are largely based on stone tools, since they – along with some scanty bone traces and a few other robust artifacts – are among the few traces capabile of surviving through the eons. Yet stone artifacts don't come stamped with a production date, leaving researchers to rely on surrounding clues to determine their age and place in history.

The Korolevo archaeological site is a spectacular one. It reaches a depth of 14 meters (46 feet) of layers that have accumulated over time, from which thousands of artifacts have been excavated, dating back many millennia. The site has known at least seven separate periods of hominid occupation, across at least nine Paleolithic cultures up until about 30,000 years ago.

But there are no biological remains at the site, only stone, which rules out the usual the typical method of radiocarbon dating any nearby organic materials. Over the decades since the tools' discovery, researchers could only guess at their age.

Fortunately recent advances have finally allowed for precision dating of buried rock, and this is what a team led by archaeologist Roman Garba of the Czech Academy of Sciences turned to.

"To answer the questions posed by archaeology and anthropology, we need to utilize the methods of both nuclear physics and geophysics," Garba says.

The technique they used is called cosmogenic nuclide burial dating, which makes use of the fact material exposed on the surface is bombarded with cosmic rays. By comparing the decays of specific atomic nuclei, it's possible to measure the amount of time that's passed since the object last saw the sky.

"At the Korolevo site, we specifically measured the concentrations of cosmogenic nuclides beryllium-10 and aluminum-26, which have different half-lives," Garba explains.

"These nuclides accumulate in the quartz grains when the rock is at the surface due to cosmogenic radiation from space, but they begin to decay when they become buried in the ground. The ratio of the two varies according to how long the clasts were buried beneath the ground surface. This allows us to calculate their age since burial."

The team also used their own mathematical-based modeling to determine the age of the sediment layers, the first time this method has been used for archaeological dating. The earliest age they obtained using this method was 1.42 million years, for the oldest tools in the assemblage.

The dating of the artifacts has allowed the researchers to fill in some of the gaps in the history of human migration. Their research shows that Homo erectus was in Europe by 1.4 million years ago, having migrated through Asia 1.8 million years ago. The oldest known Homo erectus fossil dates to 2 million years ago, found in fragments in a cave in South Africa and painstakingly pieced together.

Obviously there are still a lot of things we don't know, but this is a step in the right direction, the researchers say.

"It remains to be seen whether this was part of a more extensive and as yet undiscovered occupation of Europe at this time," Herries says.

The research has been published in Nature.