A US woman diagnosed with the highly contagious bacterial infection tuberculosis has been found in civil contempt after repeated refusals to follow orders for treatment.

According to a press release by the Tacoma-Pierce County Health department in Washington, a warrant has been issued for the arrest of the unidentified 42-year-old woman, who will be taken to "a specially designated facility at the Pierce County Jail for isolation, testing and treatment."

"In each case like this, we are constantly balancing risk to the public and the civil liberties of the patient. We are always hopeful a patient will choose to comply voluntarily," says health department spokesperson Nigel Turner.

"Seeking to enforce a court order through a civil arrest warrant is always our last resort."

That 'last resort' came after a year of working with family and community members to encourage the woman to comply with therapies targeting the disease.

Going to court for the 16th time, the woman was finally given three options – take the medication, stay at home, or go to jail.

Extreme as the outcome might sound, tuberculosis is a serious threat to public health. Thanks to careful management of monitoring, testing, and treatment, the disease is now relatively rare in the US.

Yet worldwide it continues to infect more than 10 million individuals each year, with 1.6 million deaths tallied in 2021, making it the 13th leading cause of death around the globe.

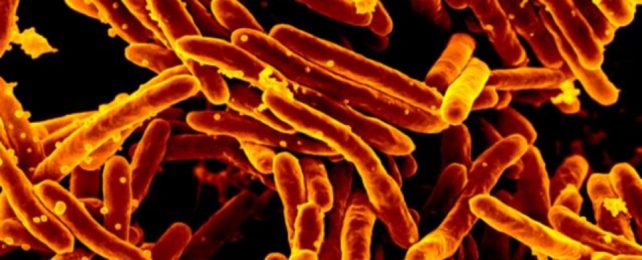

The disease is caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which loves nothing more than to nestle down inside white blood cells inside the lung's air sacs.

Primed to destroy invaders like M. tuberculosis, the white blood cells seal the microbe inside membranes and flood them with destructive agents in an attempt to break them down.

That would be the end of the bacterium, if not for a thick coat that keeps it safe and sound, allowing it to replicate inside the very cells tasked with keeping our bodies safe.

Eventually the white cell dies, though the immune system continues to do its best to destroy the invader, throwing more killer cells and protective tissues at the encapsulated bacterium in an effort to seal it away and get rid of it.

The carnage of dead cells and protective growth results in a tiny granuloma known as a tubercle, giving the disease its name and providing pathologists with a visible means of detecting the microscopic invader using X-rays.

If these little pearls of infection spread through the body, they can occupy just about any tissue, raising the risk of death dramatically. Coughed into the air inside microscopic droplets of fluid, they can easily spread into the lungs of others nearby, posing a serious health risk to the general community.

Treatment of the active form of pulmonary tuberculosis usually takes the form of a six month course of antibiotics, though an increasing number of strains are developing resistance to the more common antibacterial drugs.

In many cases, infections fall quiet, only to periodically flare up throughout a person's life. To reduce the chance of drug resistance arising in populations, these latent cases aren't typically treated with antibiotics, but are closely monitored for ongoing risk.

Exactly why the Tacoma woman refused treatment of her own active case isn't clear. It's alleged by the health department that despite beginning the months-long treatment, she refused to continue to completion.

Symptoms of active tuberculosis can clear within a few weeks of commencing a course, leading some to believe they are no longer at risk.

In January 2022, the woman was issued a court order to remain isolated at home until her condition was no longer considered active. Repeated court orders were disobeyed, including an occasion where she put hospital workers at risk by not disclosing her infection following a vehicle accident.

This is just the third time in the past two decades that Tacoma-Pierce County Health officials have sought such extreme civil action to force compliance in treatment of tuberculosis.

Yet history is full of examples where authorities have faced similar decisions between personal liberty and the risk of a public health crisis.

Perhaps the most famous is the case of 'Typhoid Mary' Mallon, an Irish-born American who is believed to have infected more than a hundred people early last century with the pathogen Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi (S Typhi), which she carried in her gut and spread in her role as a cook.

While she herself was symptomless, infections in others would lead to several deaths. Forced into quarantine by authorities, Mallon would pass away after almost 30 years spent in isolation.

Today, this highly contagious disease is also easily treated with antibiotics, though it too could pose a more serious risk one day as it develops new means of evading front line drugs.

With the rise of drug resistance, health misinformation, and the ever-present risk of new epidemics, cases such as these will increasingly become examples of lost liberty, or of reluctant, last resort measures of protection.