As 2017 drew to a close, House Speaker Paul D. Ryan (R-Wis.) urged Americans to have more children.

To keep the country great, he said, we're "going to need more people."

"I did my part," the father of three declared.

Ryan's remarks drew some eye rolls at the time, but as new data about the country's collapsing fertility rates has emerged, concern has deepened over what's causing the changes, whether it constitutes a crisis that will fundamentally change the demographic trajectory of the country — and what should be done about it.

Women are now having fewer babies and at older ages than in the past three decades, a change that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) reported this year, and which was confirmed this week with the release of additional data that shows that the trend holds across races and for urban and rural areas.

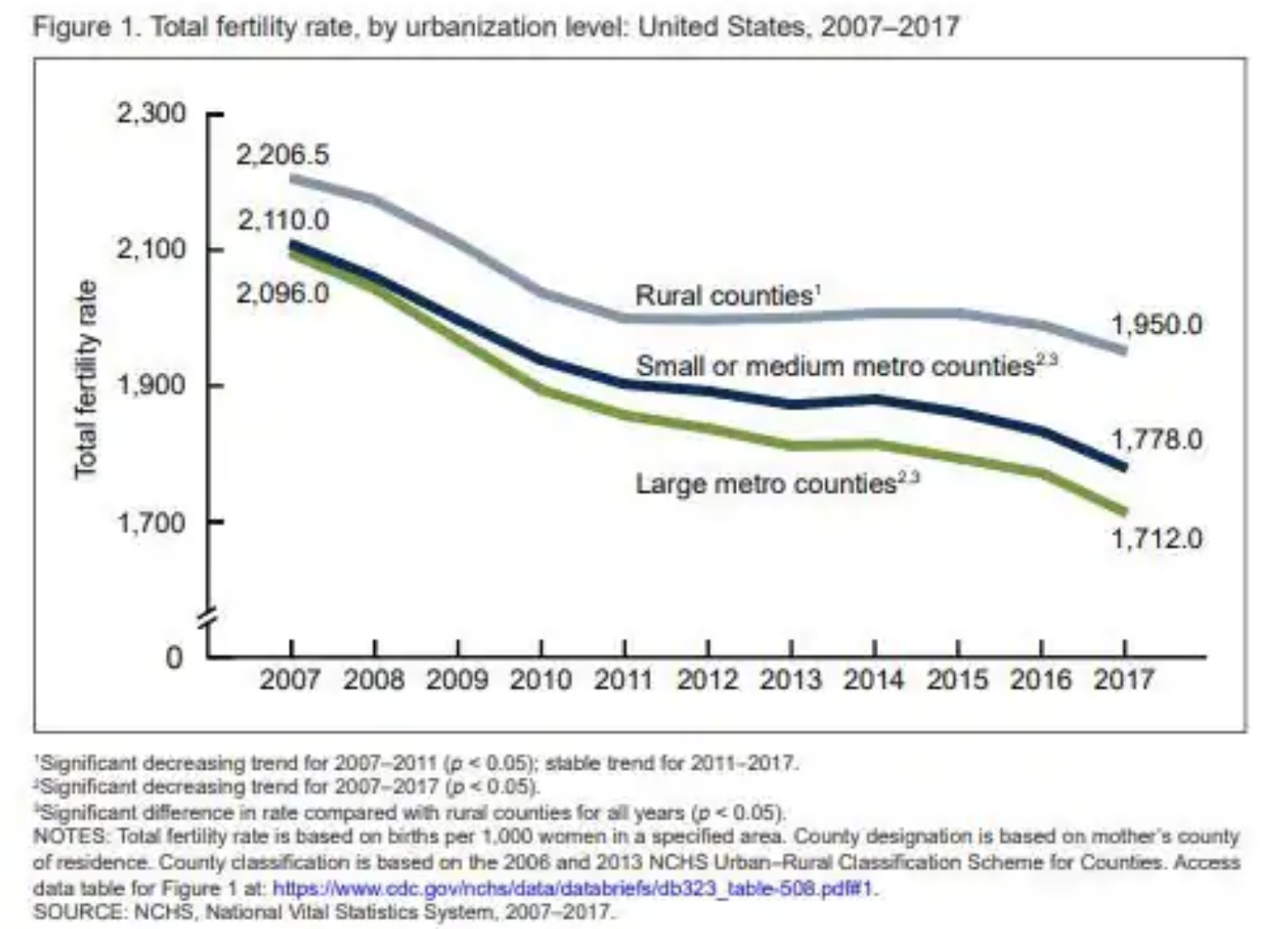

The CDC said Wednesday that the total fertility rate — a theoretical figure that estimates the number of births a woman will have in her lifetime — fell by 18 percent from 2007 to 2017 in large metropolitan areas, 16 percent in smaller metro areas and 12 percent in rural areas.

A similar downward trend holds for white, black and Hispanic women.

From 2007 through 2017, total fertility rates declined for each urbanization level, but differences between rural and metro counties widened.

Fertility and birthrates are among the most closely monitored indicators of a country's economic health. When too high, a surging youth population might be unable to find work and become susceptible to unrest.

When too low, economies can rapidly contract, and a small working-age population has to support a large retired population.

The United States is somewhat more buffered because of its relatively high levels of immigration, but if the decline in fertility continues, demographers say, the country may face an extreme population imbalance in the future.

Theories — social, economic, scientific, environmental — about why fertility is falling so sharply in the United States abound. Many agree that cultural shifts, such as women getting married later and focusing on education or work, play a big role.

But there's considerable debate, some of it more political than evidence-based, about other possible causes.

Economist Lyman Stone has blamed the United States' less-than-generous parental leave and pay policies.

Human Life International, a missionary group, blames "pro-abortion population control groups like Planned Parenthood."

Tucker Carlson claims it has to do with immigration, arguing that immigrants drive wages down, which hurts the attractiveness of men as potential spouses — "thus reducing fertility."

Some have even wondered whether the decline might be influenced by sperm quality.

Recent medical journal publications have indicated that exposure to pollutants might be harming reproductive health, including the motility and quantity of sperm, which could delay childbearing and overall fertility.

The University of Pennsylvania's Hans-Peter Kohler, who studies fertility and birthrates, said the data indicated that many shifts affecting fertility are occurring "in the transition to adulthood."

The biggest recent drops in birthrate have been among teenagers as well as people in their 20s. In 2016, the teen birthrate hit at an all-time low after peaking in 1991.

"The declining total fertility rates are children not born in the moment, but the hope is that they are delayed, not forgone," Kohler said.

"The exact details we won't know until the young adults who are currently delaying having children are in their 30s or 40s."

William H. Frey, a demographer with the Brookings Institution, said that what struck him about the new report is the figures on Hispanic women, who have traditionally had high fertility rates.

From 2007 to 2017, Hispanic women experienced a 26 percent drop in fertility rates in rural areas, a 29 percent drop in smaller metro areas and a 30 percent decline in large metro areas.

He said the fertility rates for Hispanic women in urban areas are now below the "replacement rate" of 2.1 children per woman, which would keep the population stable.

"They may be following the same pattern as the rest of the population," Frey said, an important finding that should figure into the debate over immigration.

John Rowe, a professor of health policy and aging at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, predicts that fertility rates will drop even lower in the coming years.

He said he thinks the country should be ready to deal with the impact on Social Security and the workforce but that he does not believe there's reason to panic.

He said that some other wealthy countries, such as Japan and Germany, are grappling with low fertility rates, and there's a lot to learn about how they have managed their smaller workforce to maintain high productivity.

"The emphasis should not just be on the number of people but their productivity. So we have to invest in education to enhance the productivity of younger individuals to compensate for reduction in numbers," Rowe said.

2018 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.