In late 2024, astronomers spotted asteroid 2024 YR4 on a trajectory that could potentially threaten Earth. This observation triggered a fervid series of observations of the object – possibly as big as a football field – to determine that it will not hit. However, an impact on the moon cannot be ruled out.

Then in January of this year, the near approach of an asteroid perhaps a million times more massive went almost unnoticed.

Asteroid 2024 YR4 has a diameter between 40 to 90 metres and was referred to as a "city-killer" capable of causing regional damage and affecting the climate; the larger asteroid, 887 Alinda, is over four kilometres in diameter and could cause a global extinction event.

Alinda remains just outside Earth's orbit, while 2024 YR4 does cross our orbit and still could impact Earth; however, this won't occur in the foreseeable future.

Asteroid orbits

Both 887 Alinda and 2024 YR4 orbit the sun three times for every time the massive planet Jupiter goes around once. Since Jupiter's orbit takes 12 years, the asteroids will take four years to be back on similar paths in 2028. These special kinds of asteroids are dangerous, since they come back regularly.

Alinda was discovered in 1918 and has made several sequences of near passes at four-year intervals. 2024 YR4 has made what NASA considers close passes every four years since 1948, but was only recently noticed.

Not since the 1970s has so much attention been paid to asteroids with a three-to-one relation to Jupiter. Such relationships had already been noted as a curiosity by American astronomer Daniel Kirkwood in the late 1800s.

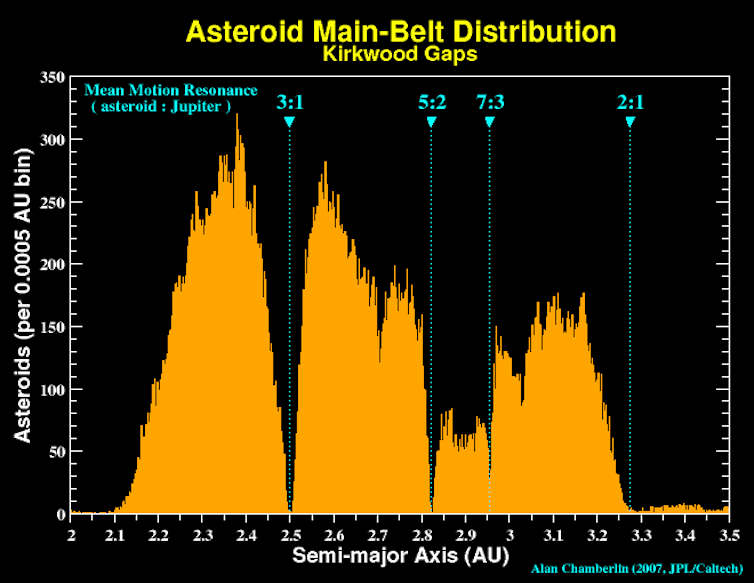

Working with very sparse data since few asteroids were known at the time, he noted none went around the sun twice for each Jupiter orbit, nor three times, nor in more complex ratios like seven-to-three or five-to-two.

These so-called Kirkwood gaps are not obvious since they show up only in plots of the average distance of asteroids from the sun. The gaps remained a mere curiosity of the solar system for about 100 years.

The employment of new computer technologies to calculate orbits revealed the effects of resonance to scientists in the 1970s. Resonance occurs when asteroids appear to move at the same, or a multiple of, the orbit speed of another external object – in this case, Jupiter.

The Kirkwood gaps are explained by asteroids similarly interacting with Jupiter to leave the asteroid belt, even while their average distance from the sun does not change. By dipping into the inner solar system, these asteroids are often removed from the gaps in a very simple way: by hitting an inner planet like Mars, Venus or Earth.

Scientists also found that these gaps were not completely empty; Alinda, for example, was in the three-to-one gap. Many more such asteroids have been found, and they are generically named "Alindas," after the prototypical first discovery whose name origin is a bit obscure.

Return of the asteroids

If the bad news is that Kirkwood gaps are due to asteroids hitting inner planets, including Earth, can it get much worse? For Alinda-class asteroids it does. Alindas follow their pumped-up orbit every four years, so properly aligned Alindas get a chance to hit Earth about that often.

Near passes of these asteroids tend to happen spaced by longer intervals, but when aligned, they come back several times with four-year spacing. A limiting factor is how tilted their orbits are: if they are quite tilted, they are not often at a "height" matching Earth's, so are less likely to hit.

The bad news about that is that both Alinda and 2024 YR4 are very nearly in the plane of Earth's orbit, and are not tilted much, so are more likely to hit.

The resonant "pumping" stretching the orbit both inward and outward from the asteroid belt has already made 2024 YR4 cross Earth's orbit, giving it a chance to impact. The much more dangerous Alinda is still being pumped: in about 1,000 years, it may be poised to hit Earth.

One piece of good news is that 2024 YR4 will miss in 2032, but by coming close it will be kicked out of its Alinda orbit. It will no longer come back every four years.

However, getting an orbital kick from Earth, its orbit will still cross ours, just not as often. The current orbit shows a somewhat close approach (farther than the moon) in 2052, and beyond that, calculations are not very accurate.

Other asteroids

Although Earth is a small target in a big solar system, it does get hit.

If 2024 YR4 managed to sneak up on us in 2024, can other asteroids also surprise us? The last damaging one to do so appeared undetected on Feb. 15, 2013, over Chelyabinsk, Russia, injuring many people when its shock wave shattered glass in buildings.

In 1908, a larger explosion took place over Tunguska, Russian Siberia, a remote region where huge areas of forest were devastated but few people injured.

Keeping watch

While astronomers work diligently to survey the night sky from Earth's surface, space-based surveys like the upcoming Near-Earth Object (NEO) surveyor can be very efficient in detecting asteroids. They do so by their heat (infrared) radiation and, being in space, can also study the daytime sky.

According to Amy Mainzer, lead on the NEO surveyor, "we know of only roughly 40 per cent of the asteroids that are both large enough to cause severe regional damage and closely approach Earth's orbit."

Once launched in late 2027, NEO will "find, track and characterize the most hazardous asteroids and comets," eventually meeting the U.S. Congress-mandated goal of knowing of 90 cent of them.

Among asteroids, we must pay special attention to resonant ones, such as 2024 YR4, because eventually, they'll be back.![]()

Martin Connors, Professor of Astronomy, Mathematics, and Physics, Athabasca University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.