Spending time in the weightless environment of microgravity can have some dramatic effects on the human body, but scientists have recently discovered a new one that could help explain why some astronauts struggle to adjust after returning to Earth.

Following a stint in space as short as a few weeks, astronauts can develop measurable changes in the very shape of their brains. For longer stretches of space travel, the alterations can linger for at least six months.

These shifts are subtle – just a few millimeters at most – but they seem to persist most strongly in the brain regions associated with balance, proprioception, and sensorimotor control, which may underlie the prolonged struggle of some astronauts to regain balance in Earth's gravity.

Related: Spaceflight Accelerates Aging of Human Stem Cells, Study Finds

"We demonstrate comprehensive brain position changes within the cranial compartment following spaceflight and an analog environment," writes a team led by physiologist Rachael Seidler of the University of Florida.

"These findings are critical for understanding the effects of spaceflight on the human brain and behavior."

When astronauts spend time in space, their tissues tend to shift around quite a bit. Without the modifying effects of gravity, fluids in the body start to redistribute themselves more evenly.

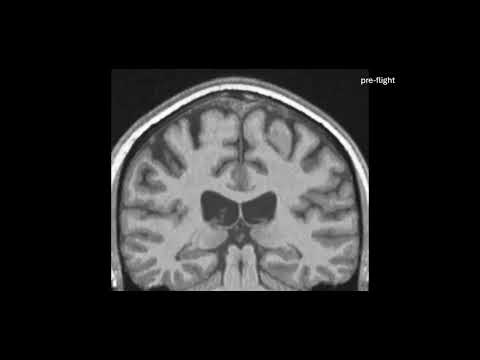

That's not especially problematic, but it does alter how the brain sits inside the skull. Previous research has shown that the center of mass of astronauts' brains shifts upward in their skulls after spaceflight, compared to measurements taken before spaceflight.

That's not the only clue that things can get a little peculiar in there. A 2015 study on people confined to a tilted bed with their heads pointing downward – an Earth-based study technique to mimic the fluid redistribution effects of microgravity – also found changes not just in the center of gravity but also in the volume of certain regions of the brain.

Seidler and her colleagues wanted to take these hints and clearly quantify exactly what happens to astronauts' brains when they spend time in space.

Their study involved 26 astronauts – 15 whose brains were measured before and after spaceflight as a deliberate part of the study, and 11 whose pre- and post-spaceflight brain measurements were included in previously published papers.

Their analysis included the brain measurements of 24 participants of a 60-day bed-tilt study conducted by the European Space Agency.

Their detailed measurements showed that the brain shifts up and back in the skull during spaceflight, and also tilts backwards a little bit too, a tiny, subtle roll, consistent with the findings of previous studies.

However, the brain shifted in other ways, too; not uniformly all over, but with different regions changing in different directions, in a way that can't be attributed to the movement of the entire brain.

That suggests that the very shape of the brain changes. The most pronounced shifts were observed in longer spaceflights – the brains of astronauts who spent a year in space could change by as much as two to three millimeters.

This was supported by data from the bed-tilt study, which also showed that the ventricles – fluid-filled pockets in the brain – also shift upward in microgravity and analog microgravity, strongly implicating fluid redistribution in the changes.

None of this was linked to a change in personality, intelligence, or cognition. Rather, the greatest changes seemed to affect brain regions involved in functions that help the brain track the body's position and movement in space.

The biggest changes took place in the posterior insula, the region of the brain that processes balance. The strongest shifts in this region, the researchers found, were linked with worse balance after returning to Earth. Astronauts often report struggling with their stability for days to weeks after landing, with more subtle sensorimotor recovery continuing for months.

If changes to the shape of the brain play a role in astronaut recovery, this information could help scientists design better programs to restore their bodies to Earth mode.

"This work advances our understanding of neuroanatomical changes with microgravity and provides quantitative outcome targets for developing interventions and optimizing postflight recovery strategies to safeguard astronaut health in future space exploration endeavors," the researchers write.

"The health and human performance implications of these spaceflight-associated brain displacements and deformations require further study to pave the way for safer human space exploration."

The findings have been published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.