The closest potentially habitable planet ever found has been spotted by Australian scientists, and it's just 14 light-years away. That's 126 trillion kilometres from Earth, which sounds impossibly far, but when you consider that our closest planetary neighbour, Mars, is 249 million km away, that handful of light-years doesn't seem so bad in the scheme of things.

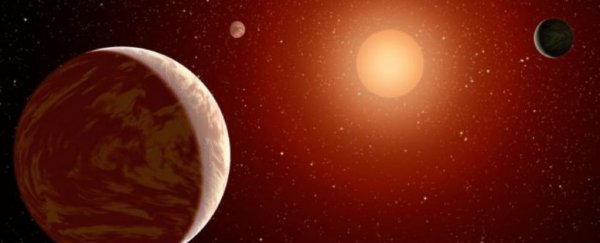

Named Wolf 1061c, the newly discovered planet is located in the constellation Ophiucus, and its star is the 35th closest star from Earth - that we know about. The team behind the discovery says it's orbiting a red dwarf 'M-type' star called Wolf 1061, alongside two other planets. All three are suspected to be rocky like Mars, rather than gaseous like Neptune.

"It is a particularly exciting find because all three planets are of low enough mass to be potentially rocky and have a solid surface," said lead researcher Duncan Wright, an astronomer at the University of New South Wales (UNSW). "The middle planet, Wolf 1061c, sits within the 'Goldilocks zone' where it might be possible for liquid water - and maybe even life - to exist."

Of the three planets, the one orbiting closest to Wolf 1061 would be far too hot for life, and the furthest away one is very likely too cold. But the one in the middle, Wolf 1061c, looks to be just right for life… potentially.

Not that that means Wolf 1061c is anything like Earth. It has a mass around 4.3 times that of our planet, and orbits its star every 18 days at a distance of around 10 percent Earth's orbit of the Sun. In our Solar System, that would make Wolf 1061c far too hot for life, but the Wolf 1061 star is much cooler than our Sun, with surface temperatures of around 3,300 Kelvin. The surface of our Sun, on the other hand, regularly hits 5,800 Kelvin.

"This discovery is especially exciting because the star is extremely calm," Wright told Stuart Gary at ABC News. "Most red dwarfs are very active, giving out X-ray bursts and super flares, which spells doom for any life, given the habitable zone is so close into these stars."

He adds that this proximity to the star means that Wolf 1061c is likely to be 'tidally locked', which means one side will always be facing its star. "This changes the circumstances on the surface of the planet substantially," he told Marcus Strom at The Sydney Morning Herald. "You have one very hot side and one very cool side."

Wright and his team used atmospheric modelling to figure out that the heat from the hot side is likely circulating to the cold side due to very high winds that travel between them.

To find Wolf 1061c in the first place, the astronomers used data collected by the HARPS spectrograph at the European Southern Observatory's 3.6-metre telescope in Chile over the past decade. They applied the 'doppler wobble method' to identify the planets, which picks up on the signal changes caused by smaller objects like planets circulating larger objects like stars.

The team will continue investigating the Wolf 1061 trio, picking up on characteristics they can glean from how they transit in front of their star. "The close proximity of the planets around Wolf 1061 means there is a good chance these planets may pass across the face of the star," one of the researchers, Rob Wittenmyer, told Strom. "If they do, then it may be possible to study the atmospheres of these planets in future to see whether they would be conducive to life."

The discovery will be published in an upcoming editon of The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

UNSW Science is a sponsor of ScienceAlert. Find out more about their world-leading research.