Artists like to anthropomorphise stars as pretty ladies, but in truth, they can be violent bastards. And astronomers have found a particularly bloodthirsty example in a binary star 3,000 light-years away, in which a small dead star slowly and periodically strips its binary companion of gas.

This type of interaction is known as a cataclysmic variable star, but you may know it by its more popular name - a vampire star.

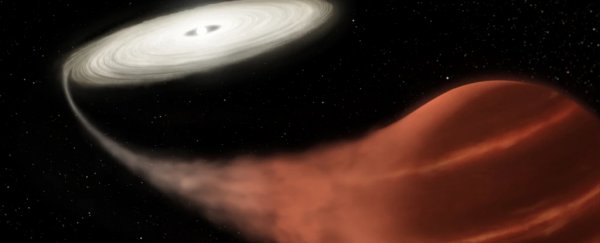

These are binary systems where the smaller star, usually a white dwarf (the compact core of a dead star around the mass of the Sun), goes through bursts of siphoning material off its larger companion.

But in the case of this system, the dynamic is even weirder: the binary companion is a brown dwarf, an object that started to form just like a star, but couldn't accrete enough mass to kickstart hydrogen fusion in the core. Such objects are sometimes called "failed stars", with a mass between gas giant planets and small stars.

This particular brown dwarf was 10 times less massive than the white dwarf in the binary system.

The event was found in archived data collected by the Kepler space telescope in 2016. The space telescope had captured the star brightening massively, but the data had been archived without the event being detected.

But an automated program recently set to sifting through the data looking for changes in stars - what are known as transient events - found it.

"The rare event we found was a super-outburst from the dwarf nova, which can be thought of as a vampire star system," explained astronomer Ryan Ridden-Harper from Australian National University.

"The incredible data from Kepler reveal a 30-day period during which the dwarf nova rapidly became 1,600 times brighter before dimming quickly and gradually returning to its normal brightness."

That brightness was produced by material swirling around the white dwarf in an accretion disc - the same process that occurs on a much larger scale around supermassive black holes. The swirling disc generates such intense heat through friction that it incandesces.

In turn, this produces the star's transient events. Because the star isn't feeding constantly, it dims and brightens; a previous Kepler observation campaign in 2014 also included the star, which at that time was not feeding, thus providing the automated program with a baseline.

This outburst is not what the automated program was designed to find. The target is, the researchers said, extreme energetic events such as core-collapse supernovae and neutron star collisions.

But, as Isaac Asimov famously noted, "The most exciting phrase to hear in science, the one that heralds new discoveries, is not 'Eureka' but 'That's funny…'"

"The discovery of this dwarf nova was unexpected, since it wasn't what we were searching for, but it provided excellent data and new insights into these vampire star systems," Ridden-Harper said.

And it also shows that the program can exceed its design parameters to find transient events astronomers didn't think to use it for.

But there was something else a bit odd. The rise in brightness was inconsistent, in a manner observed in other dwarf-nova super-outbursts - suggesting, the researchers said, new physics behind these types of outbursts.

"The next steps for this project are to comb through all Kepler data and extend it to data from the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, which is known as TESS," Ridden-Harper said.

"This will give us the best understanding of the most rapid explosions in the Universe. Along the way, we might discover some rare events that no other telescope could find."

The research has been published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.