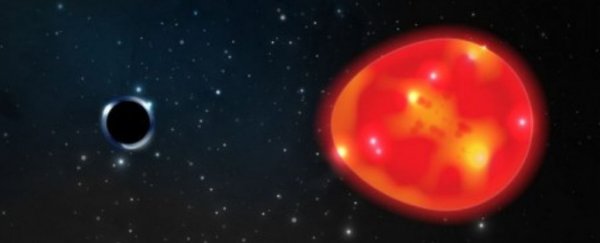

Astronomers think they have discovered a tiny black hole, with a mass so small it places it in an exclusive category. Best of all, it's excitingly close by.

Roughly 1,500 light-years from our own planet, in a Milky Way constellation known as Monoceros, this is the closest black hole candidate to our planet scientists have yet had the fortune to find.

The team at Ohio State University have named it the Unicorn - a hat tip to the black hole's home and its exceedingly rare nature.

"When we looked at the data, this black hole – the Unicorn – just popped out," says astronomer Tharindu Jayasinghe.

So how did we not see it before? As it turns out, we had our astronomical blinders on.

From tiny primordial ones to supermassive giants powering the hearts of galaxies, theory predicts that black holes can exist in a range of masses. However, when it comes to black holes formed by the collapsing cores of dead stars, astronomers have found some 'mass gaps' over the years.

If a star collapses down to roughly less than 2.3 times the mass of our Sun, it ends up being a neutron star, not a black hole. And, until recently, we hadn't found any stellar black holes smaller than 5 solar masses - which leaves us with the mass gap.

Before we'd found any objects in that gap, their existence had been so dubious that when astronomers noticed a nearby red giant star tugged by something, they initially dismissed the possibility that it was a tiny unseen companion.

But Jayasinghe looked at it in a different way. As a graduate student, his supervisor had told him of the potential for exceedingly small black holes, and he wanted to investigate.

Analyzing data from various telescope systems and satellites, he honed in on a red giant in the Monoceros constellation, which was in its last stages of life.

The velocity of the star and the way it was being tugged by gravity all suggested there was a tiny black hole orbiting it. The size of this dark and silent companion was calculated to be roughly 3 solar masses.

"Just as the Moon's gravity distorts the Earth's oceans, causing the seas to bulge toward and away from the Moon, producing high tides, so does the black hole distort the star into a football-like shape with one axis longer than the other," explains astronomer Todd Thompson, who has helped find other tiny black holes in the past.

"The simplest explanation is that it's a black hole – and in this case, the simplest explanation is the most likely one."

For decades, it was unclear if anything existed in the mass gap between two forms of dead star.

The Unicorn now joins several other tiny black holes to help solve that mystery. The results have yet to be officially verified, but for now, this seems like a strong candidate for yet another black hole smack in the middle of the mass gap.

"I think the field is pushing toward this, to really map out how many low-mass, how many intermediate-mass, and how many high-mass black holes there are," says Thompson, "because every time you find one it gives you a clue about which stars collapse, which explode and which are in between."

Who knows how many more tiny black holes are out there for us to find. Ready or not, here astronomers come.

The results have been accepted for publication in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society and the preprint can be found here.