This is what will happen when our Sun dies:

First, the hydrogen-powered nuclear reactor in its center will run out of fuel. The Sun will expand into a red giant, swelling to 100 times its size and swallowing Mercury, Venus and perhaps even our own planet, along with all life as we know it.

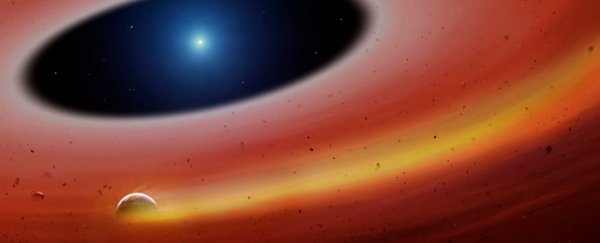

Next, it will churn through the helium in its core, fusing those atoms into carbon until it lacks the materials and energy to continue. Finally, it will convulse and collapse, shedding its outer layers until all that remains is a dense, glowing sphere not much bigger than Earth - a white dwarf.

No one can say what our solar system will look like after that cataclysm, some 5 billion years in the future. But a newfound planetary system might offer a clue.

In the pale gleam of a white dwarf 410 light-years from Earth, the heavy metal core of some body, which may have been a planet once, drifts amid the wreckage of its former self.

The strange, shattered world, described Thursday in the journal Science, is only the second body ever found orbiting this type of dead star.

It is evidence, scientists said, of what happens to planetary bodies when their suns go extinct - a fate that awaits most solar systems in the universe, including our own.

"We have this glimpse into our possible future," said Jessie Christiansen, an astronomer at NASA's exoplanet science institute who was not involved in the new study.

"It's exciting" - if slightly terrifying - "and you can imagine that happening here."

The host star of the newly discovered planet fragment is a white dwarf, known as SDSS J122859.93+104032.9. (To save time and breath, the scientists who study it call it simply, "1228".)

Christopher Manser, an astrophysicist at the University of Warwick in Britain, was first drawn to 1228 several years ago because it appeared to have a debris disk swirling around it.

Using the world's largest optical telescope, the Gran Telescopio Canarias in Spain, he sought to split the light signature of the debris disk into its component parts, which would tell him what it was made of.

He was surprised to see regular disruptions in the disk - a stream of gas not unlike what comes from a comet's tail. A year of observations showed that the gas kept showing up every two hours, like clockwork.

Such a regular signal could only be produced by a "planetesimal", or planet fragment, orbiting the extinct star and somehow blowing off gas.

The newfound world's two-hour orbital period is so short that it must be incredibly close to the white dwarf; if you plopped it down in our solar system, it would be inside the atmosphere of the sun.

It must also be incredibly resilient. A white dwarf packs the mass of nearly an entire sun into a sphere 1 percent of the sun's size. These objects have enormous gravitational pull that could easily rip a planet apart.

"This body has to have a high enough density or internal strength to survive this intense gravity," Manser said. "The densest thing we could think of was iron."

There is one world in our solar system like this: the all-metal asteroid 16 Psyche. Scientists think this strange body was once the iron heart of a larger planet whose rocky crust and molten mantle were stripped away.

Perhaps the planetesimal has the same origin story: Born as a regular, rocky world farther out in the solar system, it got pushed toward the white dwarf by some passing disturbance. In the clutches of the dead star's tremendous gravity, the fragile crust and mantle disintegrated, leaving behind the tough metal core.

Observations of the white dwarf's debris disk support this notion. It is full of calcium, oxygen and magnesium - "the prominent building blocks of rocky bodies," Manser said.

But there are lingering questions about this strange little world. Manser and his colleagues aren't sure what exactly is causing the gassy disturbances in 1228′s debris disk.

It may be that the gases are evaporating off the surface of the planetesimal. An alternative hypothesis suggests that the iron world's presence causes collisions in the debris disk that generate gas.

Meanwhile, the scientists hope to spot more planetary systems like this one. Many white dwarfs show evidence of "pollution" by rocky material, and at least six appear to be surrounded by debris disks.

"All of that suggests that up to half of all white dwarfs have planetary systems that survived their evolutions and are flinging in material," Manser said.

Astrophysicist Lisa Kaltenegger, the director of the Carl Sagan Institute at Cornell University, pointed out that the majority of all stars in the universe are destined to become white dwarfs after they die. (Only stars that are much more massive than the Sun are big enough to explode into a supernova and eventually form a black hole.)

Kaltenegger, who was not involved in the most recent study, published an analysis last year in the Astrophysical Journal Letters suggesting planets in the right orbit around a white dwarf could potentially be habitable for billions of years.

This latest discovery "is the first puzzle piece that there could be planets around white dwarfs, and they can be there for a while," she said.

"Whether or not you can envision a second genesis [of life] around these remnant stellar cores," she added, "it's still beautiful to envision."

2019 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.