Exoplanets. They're very small, and very far away. We usually have to detect them by indirect means. Direct images are rare, and not very detailed. Even working out what's in their atmosphere is difficult. So you'd think trying to analyse their interiors would definitely be in the too-hard basket.

But you'd be wrong. A team of astronomers from the University of California Los Angeles has found a way, and it's utterly brilliant. They've analysed the chemical signatures of rocky bodies such as planets and asteroids in the spectra of white dwarf stars, into which the rocky bodies previously crashed.

Not only is this a remarkable new technique - it also suggests that the insides of exoplanets are geochemically similar to Earth's.

So how do you figure out what's exoplanets are made of? Imagine if Mercury, Venus and Earth were to crash into the Sun. The elements in the planets would be absorbed into the Sun, and change the light it emits, if only a canny astronomer could figure it out.

"By observing these white dwarfs and the elements present in their atmosphere, we are observing the elements that are in the body that orbited the white dwarf," explained astrochemist Alexandra Doyle of UCLA.

"Observing a white dwarf is like doing an autopsy on the contents of what it has gobbled in its solar system."

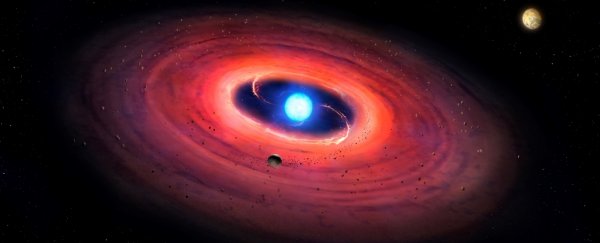

White dwarfs are the ultradense cores of dead stars that started out below 10 solar masses (larger than that, and they turn into neutron stars; larger again turns into black holes).

When the star runs out of hydrogen to burn, it will inflate into a red giant, fusing helium and carbon until those elements are depleted, too. Then the star's outer layers will be blown off, and the brightly shining, ultradense core that remains - the dead star's corpse, no longer fusing anything - is the white dwarf.

Doyle and her team looked at the electromagnetic spectrum produced by six white dwarf stars, between 200 and 665 light-years away. Different elements emit and absorb specific wavelengths, so when you look at the spectrum of a star, you can use these emission and absorption lines to determine its composition.

Because they're so dense, a white dwarf's atmosphere should show only the lightest elements, with heavier elements drawn into the star's interior, where they would be undetectable. But this is not what the team found.

"If I were to just look at a white dwarf star, I would expect to see hydrogen and helium," Doyle said.

"But in these data, I also see other materials, such as silicon, magnesium, carbon and oxygen - material that accreted onto the white dwarfs from bodies that were orbiting them."

And that revealed something really interesting - that the rocky planets and asteroids and other bits and pieces that had been slurped into the stars were made of similar stuff to Earth.

The clue was in the oxidation of iron - the process whereby iron's electrons are shared with oxygen, resulting in a chemical bond between them, and producing iron oxide, also known as rust.

Here in the Solar System, rocky bodies such as Mars, Earth and a whole bunch of asteroids have a high level of this iron oxidation.

It's why Mars is red. And it's also why Earth is the way it is.

"All the chemistry that happens on the surface of the Earth can ultimately be traced back to the oxidation state of the planet," said cosmochemist Edward Young of UCLA.

"The fact that we have oceans and all the ingredients necessary for life can be traced back to the planet being oxidised as it is. The rocks control the chemistry."

So, to build an Earth-like exoplanet, you'd probably need similar geochemistry. And whether or not exoplanets have this geochemistry has been a huge mystery. This is where the team's analysis of the stars' spectra comes in.

"We measured the amount of iron that got oxidised in these rocks that hit the white dwarf," Young said.

And they were very similar to Earth and Mars.

So, rocky planets that could have Earth-like atmospheres, plate tectonics, magnetic fields - they may not be incredibly rare. Just a bit harder to spot than the gas giants we usually find.

"We are doing real geochemistry on rocks from outside our solar system. Most astrophysicists wouldn't think to do this, and most geochemists wouldn't think to ever apply this to a white dwarf," Young said.

"We have just raised the probability that many rocky planets are like the Earth, and there's a very large number of rocky planets in the universe."

The research has been published in Science.