Astronomers have managed to reveal all-new details about a great, yawning 'hole' in our Sun that's nearly twice the diameter of Earth.

The giant sunspot was photographed back in 2015, but thanks to the new images, scientists can now study its dark, contorted centre in new detail - which could help us better understand the mysterious physics that power our star.

Sunspots are normal features that develop on the surface of the Sun when its magnetic field becomes extremely concentrated in certain places.

This causes a cold patch, which is why sunspots look darker in images, and can lead to huge solar flares that blast the Sun's material out into space - the solar storms that trigger spectacular aurorae here on Earth, and can interfere with our telecommunications.

We have plenty of telescopes that watch these sunspots forming on the surface of the Sun at varying wavelengths of light, but researchers have now used a telescope to image them using radio wavelengths to reveal never-before-seen detail.

The new photographs were taken with the Atacama Large Millimetre/submillimetre Array (ALMA) telescope in Chile.

"We're accustomed to seeing how our Sun appears in visible light, but that can only tell us so much about the dynamic surface and energetic atmosphere of our nearest star," said Tim Bastian, an astronomer with the US National Radio Astronomy Observatory.

"To fully understand the Sun, we need to study it across the entire electromagnetic spectrum, including the millimetre and submillimetre portion that ALMA can observe."

ALMA is usually used to detect radio waves from distant galaxies, but it was also designed to stare straight into the Sun without its equipment being scorched. And that means it can detect radio wavelengths that no other telescopes on Earth have been able to pick up.

Those two wavelengths are 1.25 millimetres and 3 millimetres. Both wavelengths probe the Sun's chromosphere, which is the area just above the surface that we see in visible light.

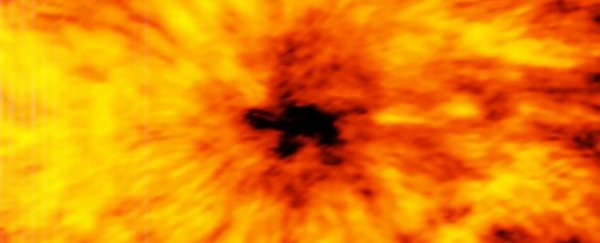

But the 1.25-millimetre images captured by ALMA show a layer of the chromosphere that's deeper than those taken at a wavelength of 3 millimetres. And interestingly, the photos are strikingly different, showing that the temperatures of the chromosphere below a sunspot change depending on how deep it gets.

This two-levelled view of the chromosphere reveals a level of detail that we've never been able to see before.

This is the 1.25 millimetres radio wavelength image:

And this is the 3-millimetre radio wavelength image:

The team now hopes that the telescope will help them figure out exactly why these two levels of the chromosphere are different temperatures, and how that can influence the formation of sunspots - a process that's still not properly understood.

"Understanding the heating and dynamics of the chromosphere are key areas of research that will be addressed in the future using ALMA," said the European Space Organisation (ESO) in a press release.

These are the very first images of the Sun taken by ALMA, and we're looking forward to seeing what the telescope reveals about our star next.

The initial data from ALMA's solar observing campaign are being released this week to the worldwide astronomical community for further study.